It was a halting moment.

Author Salman Rushdie was making his first public appearance since being attacked by a knife-wielding would-be assassin nine months ago.

Dressed in black with a small, white, priest-like collar, Rushdie paused before delivering his remarks at an event hosted by PEN America in New York City, where he had just received the group’s Centenary Courage Award.

Rushdie urged the effusive 700-strong crowd to sit, so he could begin his short, prepared address. Rushdie thanked the speakers who preceded him for their “kind words”.

Then, he reached for his reading glasses. “Otherwise,” Rushdie said, “I don’t know what I am saying.”

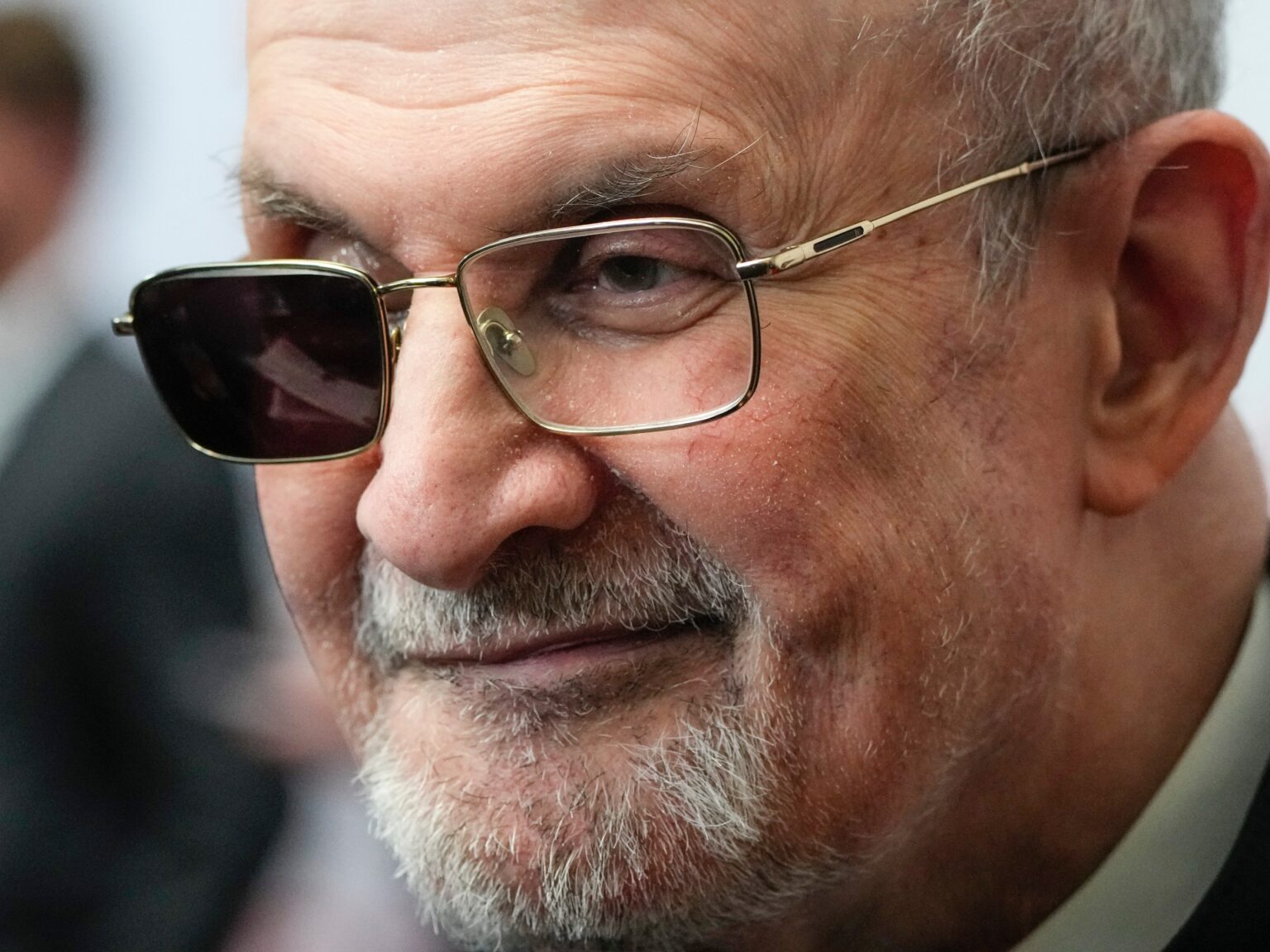

Suddenly, the auditorium went silent. Looking down, Rushdie swapped one pair of spectacles for another. Both sported blackened right lenses.

For an instant, the disfigured remnants of his now blinded right eye were revealed – the shocking residue of a shocking ambush that had one aim: to kill him.

There were other signs that the stabbing had taken a hard and permanent toll. Rushdie’s mouth seemed slightly askew. He looked gaunt and much older.

Still, Rushdie had made a remarkable recovery and was a worthy recipient of an honour intended to acknowledge his courage and will.

“Hi, everybody,” Rushdie said. “It’s nice to be back as opposed to not being back, which was also an option. I’m pretty glad that the dice rolled this way.”

The crowd laughed and applauded.

Like any great writer, Rushdie is a complicated figure who provokes complicated emotions.

His genius is undeniable. His artistry, apparent. His oeuvre is devoured by devoted readers, drawn to his stream of magical stories, born of a singular imagination, dexterity and skill.

But Rushdie has his share of detractors, too.

In an October 2017 column for Al Jazeera, the Iranian professor and literary critic, Hamid Dabashi, dismissed Rushdie as an “imposter” and a “bitter old Islamophobe” whose politics had been “corrupted” after a fatwa — which Dabashi denounced — “put a price on his head”.

I remember reading the blistering piece at the time and nodding approvingly. Dabashi, it seemed to me, had captured Rushdie’s depressing metamorphosis from artist to – as he put it so bluntly – “pestiferous Islamophobe on par and paired with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Sam Harris, Bill Maher and the rest of their detestable gang”.

I defy anyone who watched Rushdie stand and speak in that hall last week not to set aside that biting judgement, and, instead, marvel at his determination not to be deterred or silenced.

Rushdie made that point when he said: “Violence must not deter us … the struggle goes on.”

And, Rushdie has, to be sure, faced an unforgiving quota of struggles. Others would have wilted or, at the least, retreated from view.

Not Rushdie.

For decades, he confronted the prospect of being murdered at any place, at any time for penning a novel, The Satanic Verses.

Rushdie did not wilt or retreat. He continued to write. When the danger seemed to abate, he emerged from the protective cocoon set up around him and stepped back into the ring to live life to the full despite the risks.

Then, as he sat on an outdoor dais on a bright, August day in Chautauqua, New York to talk about important things, an assailant stormed the stage and began punching and stabbing Rushdie.

The lingering fear of what might happen had turned real, chaotic and bloody.

Again, Rushdie did not wilt or retreat. He fought. Tested once more, he beat death. Though damaged – in body and, no doubt, spirit – Rushdie returned to the people who love him and whom he loves, I suspect, in equal measure.

And, of course, he has returned to his legion of faithful readers – mostly strangers who are not only fond of his wit, intelligence, and immortal stories but who were among the throng of rescuers who rushed the stage to stop the horror unfolding like a surreal nightmare before them.

Rushdie thanked them. Though he did not know their names and never saw their faces, he said they deserved the honour, not him.

Often, such expressions of magnanimity are not only predictable but have an insincere tinge. Not this time. Rushdie meant it when he saluted his saviours who ran at the attacker, dislodged his knife and pinned him to the ground.

“I was the target that day, but they were the heroes. The courage that day was all theirs,” Rushdie said. “If it had not been for these people, I most certainly would not be standing here today. So, I accept this award … on behalf of those who came to my rescue and saved my life.”

He asked the audience to applaud them. It did.

True to his mindful nature, Rushdie shifted his attention to urgent matters requiring America’s attention.

Rushdie spoke of the necessity of books to bridge the estrangement between “America and the rest of the world” in the “aftermath of 9/11”.

“At least through the world of books and ideas and writers we could do something to rectify that,” he said.

The 75-year-old naturalised US citizen also urged vigilance. America, he said, has a “problem.” That problem is the state-sanctioned assault on books, teachers, and libraries.

“It has never been more dangerous, never been more important to fight,” Rushdie said.

Enlightened and literate America must, he insisted, prevail in the battle to defend the cause of free expression against homegrown evangelical zealots.

“We need to win,” Rushdie said.

While he may be scarred and slowed a little by those scars, Rushdie is bound to be on point in the struggle between ignorance and ideas, hysteria and knowledge, and wrong and right.

It is good the dice rolled your and humanity’s way, Mr Rushdie.

Welcome back.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.