Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

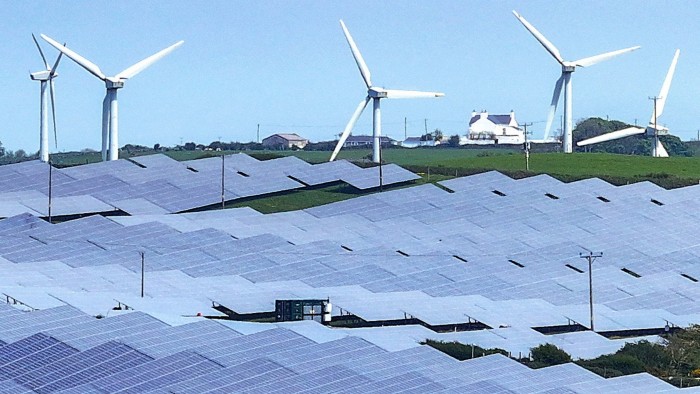

Clean energy is in trouble. Faced with huge capital needs, elevated interest rates and eroding political support, green enterprises are finding that public equity markets are not as hospitable as they used to be. Salvation comes from an unusual place: sharp-elbowed private equity groups.

Among these unlikely do-gooders are Apollo, KKR, Blackstone and Brookfield. All have become lenders in order to lean into the broadening market for private credit. Apollo, for example, says it will invest $100bn in clean energy and climate investments by 2030. No wonder: power and energy businesses have attractive qualities for would-be long-term lenders. As well as being capital-intensive, they usually produce stable and predictable cash flows.

For borrowers, private capital, as opposed to traded bonds and bank loans, can be expensive and restrictive. But they have less say these days. When public markets become unreliable, the Masters of the Universe, with their ample supply of capital, are the next best thing.

Consider the UK’s Hinkley Point nuclear facility. Last week, Apollo said it would lend up to £4.5bn on an unsecured basis to the French utility EDF for the project. The money will cost under 7 per cent, and the debt will be rated as investment grade, allowing Apollo’s own life insurance company to hold some of it. Public bonds might have been slightly cheaper for EDF, but Apollo can offer various customised features, such as letting EDF flexibly draw the money when needed.

Things get more complicated when borrowers are in dire straits. Sunnova, a US residential rooftop solar operator, recently filed for bankruptcy, as have several rivals. KKR had made an $185mn emergency loan to Sunnova in March that came with a hefty 15 per cent interest rate. The bankruptcy process is now a complex fight between the likes of KKR, Oaktree Capital and SP Atlas, a warehouse lending affiliate of Apollo.

Apollo, meanwhile, also sits at the centre of another clean energy blow-up. Wolfspeed, which makes semiconductors for electric vehicles, owes Apollo $1.5bn, a senior loan that still costs it 16 per cent a year. That debt, initially lent in 2023, gives Apollo various rights and influence over the company’s operations. For comparison, Wolfspeed borrowed $3bn by issuing a publicly traded convertible bond market a few years ago, paying a coupon of less than 2 per cent, with few strings attached.

Wall Street companies like to characterise these investments as both noble and commercially sound. It is inevitable, however, that some will prove less than harmonious. Technology will fall short, government support will ebb and flow and projections will not pan out. When that happens, private capital groups will get back to what they do best: forcefully exercising their rights as dealmakers. Their own investors expect nothing less.

sujeet.indap@ft.com

https://www.ft.com/content/793b1e2e-1b3c-454b-bddd-000390c46ac0