Every year, tens of thousands of young women opt to freeze their eggs, an expensive and sometimes painful procedure. As more Americans postpone childbearing, the numbers are growing.

But there are many unknowns: What is the optimal donor age for freezing? What are the success rates? And critically: How long do frozen eggs last?

The answers to those questions may be harder to find. In its drastic downsizing of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Trump administration abolished a federal research team that gathered and analyzed data from fertility clinics with the purpose of improving outcomes.

The dismissal of the six-person operation “is a real critical loss,” said Aaron Levine, a professor at the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School of Public Policy at Georgia Tech, who has collaborated with the C.D.C. team on research projects.

“They had the most comprehensive data on fertility clinics, and their core value was truth in advertising for patients.”

Barbara Collura, chief executive of Resolve: The National Infertility Association, said the loss of the C.D.C. team would be a setback to both infertile couples and women contemplating the freezing and banking of eggs.

The termination arrives as politicians have become increasingly concerned with falling fertility rates in the United States. President Trump has declared himself the “fertility president” and issued an executive order expanding access to in vitro fertilization.

“It doesn’t square with the White House leaning all in on I.V.F.,” Ms. Collura said.

One in seven women, married or unmarried, experiences infertility, she said: “So I just look at those statistics and it’s disappointing, if not mind-blowing, that our nation’s public health agency has decided we’re not going to talk about it or do work on it.”

Asked why the team had been eliminated, a Health and Human Services spokeswoman said the administration is “in the planning stages” of moving maternal health programs to the new Administration for a Healthy America. She did not provide other details.

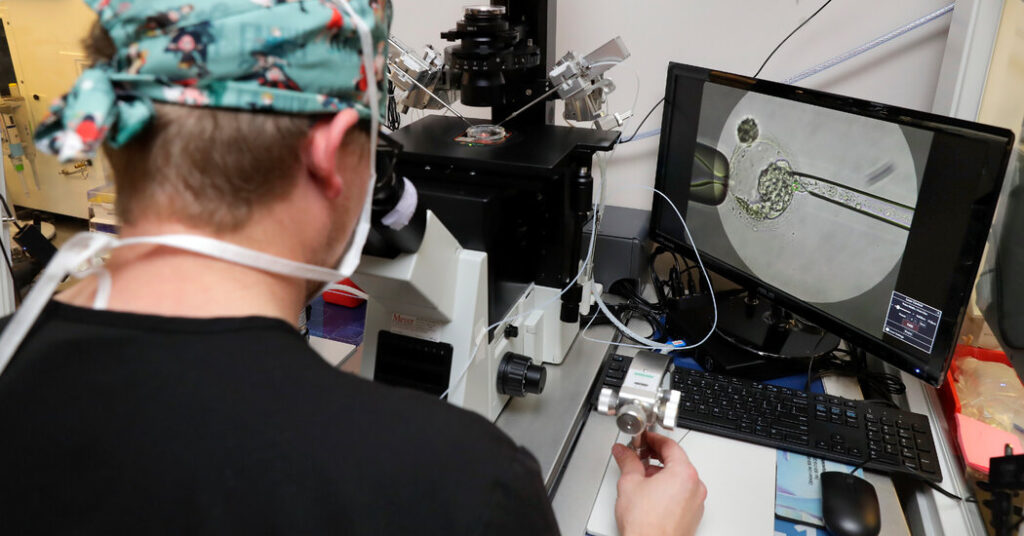

The scientists on the team, the National Assisted Reproductive Technology Surveillance System, were trying to solve a number of riddles surrounding I.V.F. Planned research included a study looking at the birthrates involving eggs and embryos that had been frozen and banked for several years.

“We don’t have great data on the success rates of egg freezing when women do it for their own personal use, just because it’s relatively new and difficult to track,” said Dr. Levine.

The unknowns weigh on women who want to have children. Simeonne Bookal, who works with Ms. Collura at Resolve, froze her eggs in 2018. She knew she wanted to have children, but was waiting to find the right partner.

Earlier this year, Ms. Bookal became engaged; the wedding will be held next spring. She is now 38, and said the banked eggs had provided her with a “security blanket.”

Though she still can’t be completely confident she will be able to get pregnant and have children, “I would be way more stressed if I hadn’t frozen my eggs.”

Precise success rates for the procedure are elusive, because many of the studies published so far are based on theoretical models that rely on data from patients with infertility, or women who are donating their eggs. They are different in many ways from women who are preserving their own eggs for future use.

Other studies are small, reporting on outcomes involving fewer than 1,000 women who have returned to thaw their eggs and undergo I.V.F., said Dr. Sarah Druckenmiller Cascante, clinical assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at NYU Langone and the author of a recent review paper on the subject.

“The data is limited, and it’s important to be honest with patients about that,” she said.

“I don’t like to think of it as an insurance policy that is guaranteed to pay out, resulting in a baby, but rather as increasing your odds of having a biological child later in life, especially if you do it when you’re young and get a good number of eggs.”

The C.D.C. team maintained a database, the National ART Surveillance System, which was created by Congress in 1992 and calculated success rates for each reporting fertility clinic. It needs constant updating, and its future is now in doubt.

The Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology has a similar database available to researchers. But it is slightly less comprehensive than the C.D.C.’s, as it only includes information from its member clinics, about 85 percent of the nation’s fertility clinics.

That database is not attended by a dedicated research team, said Sean Tipton, chief advocacy and policy officer at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Questions about the risks and benefits of egg freezing have taken on an added urgency as the number of women banking their eggs for future use has grown dramatically.

The procedure was no longer deemed experimental as of 2012. In 2014, only 6,090 patients banked their eggs for fertility preservation; by 2022, the number had climbed to 28,207. The figure was 39,269 in 2023, the last year for which data is available.