In Summary:

- Africa offers traditional dishes that may shock tourists with unusual ingredients or appearances, yet they deliver rich, flavorful experiences that reflect generations of culinary heritage.

- Many surprising foods carry deep cultural, historical, and nutritional significance, often playing key roles in festivals, family traditions, and local economies.

- The article highlights ten must try dishes and explains why they taste delicious despite their intimidating looks, showing how they sustain communities and preserve cultural identity.

Deep Dive!!

Monday, 17 November 2025 – Africa’s culinary landscape is as diverse and vibrant as its cultures, spanning deserts, savannas, rainforests, and coastal regions. Beyond the familiar staples, the continent offers a wide range of traditional dishes that often surprise first time visitors with their unusual appearances or unconventional ingredients. Some meals may initially shock or challenge newcomers, yet they deliver rich and layered flavors that reflect centuries of local knowledge, resourcefulness, and cultural heritage.

Many African foods that seem strange at first glance carry deep historical and social importance. They are prepared with time honored techniques and rely on locally sourced ingredients that maximize nutrition and flavor. Dishes made from fermented grains, insect based proteins, or gelatinous soups may look intimidating to outsiders, but they are cherished for their taste, health benefits, and connection to ancestral traditions. Understanding the stories behind these foods adds a level of appreciation that goes beyond the plate.

This article explores the top ten African dishes that tend to shock tourists while remaining celebrated for their deliciousness. Each entry reveals both the initial surprise and the reasons locals treasure these meals, guiding readers through flavors that challenge expectations and showcase Africa’s unforgettable culinary traditions.

10. Mopane Worms (Southern Africa)

A culinary icon across Southern Africa, especially in Zimbabwe, Botswana, and northern South Africa, Mopane Worms are actually the plump caterpillars of the Emperor Moth (Gonimbrasia belina). Their wrinkled, spiny appearance can be startling at first, yet once prepared, they become a deeply flavorful delicacy. After the gut is removed, they are boiled in salted water, then sun-dried or smoked, which preserves them and creates their signature crunchy texture. They can be eaten as a snack or rehydrated and fried with tomatoes, onions, and chili.

Their flavor is often a pleasant surprise. Rather than tasting earthy or insect-like, Mopane Worms offer a nutty, smoky profile that absorbs spices beautifully. When fried with aromatics, they develop a richness similar to soft-shell crab or crispy bacon, which helps explain their popularity in busy markets where they are sold in heaping baskets. This beloved snack carries nostalgia, pride, and a strong sense of place for many Southern Africans.

Nutritionally, Mopane Worms are exceptional. With a dry weight protein content above 60 percent and high levels of iron, calcium, zinc, and healthy fats, they serve as an important dietary resource in regions where meat can be costly. Their sustainability is another advantage, and they often appear in conversations about future-friendly foods. In fact, many Western researchers compare their efficiency and nutrition to the rising trend of edible crickets and mealworms in Europe and the United States.

Harvesting Mopane Worms also supports local economies. The seasonal collection provides income for rural families, particularly women and children, though concerns about over-harvesting and climate change threaten the mopane woodlands they depend on. For visitors, tasting Mopane Worms is more than a moment of bravery. It is an immersion into a tradition that blends culture, ecology, and nourishment in a way few foods can match.

9. Akpan (West Africa, particularly Nigeria and Benin)

Originating from Nigeria and Benin, Akpan is a fermented corn pudding whose thick, pale, slightly lumpy appearance often misleads first-time tasters. Although it may resemble plain yogurt or curds, it is actually a refreshing, lightly tangy dessert or breakfast dish that sits at the heart of Yoruba and Beninese food culture. West Africans have long used fermentation to deepen flavor and preserve food in warm climates, and Akpan is one of the clearest expressions of that skill.

Akpan begins with maize kernels soaked until they soften and ferment, then wet-milled into a smooth paste. After a short second fermentation, the paste is blended with coconut milk, a little sugar or condensed milk, and sometimes ginger or salt. The result is a chilled, silky pudding with a bright, tangy edge balanced by gentle sweetness. It is often served by street vendors in small cups, enjoyed at home as a cooling afternoon treat, or shared during family gatherings and ceremonies, which adds warmth and context to its cultural role.

Nutritionally, Akpan is both comforting and energizing. Fermentation makes the corn easier to digest and unlocks its nutrients; the dish delivers steady carbohydrates, B vitamins, and healthy fats from the coconut milk, along with probiotics that support gut health. It is commonly given to babies as a weaning food and embraced by adults as a soothing option during hot weather.

Akpan also has cousins across West Africa. In Ghana, a related fermented corn dish appears in the popular pairing of Koko with Koose, and throughout the region the tanginess of similar puddings can be adjusted by altering fermentation time. For visitors, tasting Akpan offers an entry into the subtle world of African fermented foods, where familiar processes create flavors and textures that feel entirely new.

8. Fufu (West & Central Africa)

A foundational staple across West and Central Africa, Fufu is a starchy dough that serves as the ultimate comfort food, though its pale, gelatinous, and somewhat sticky appearance can be perplexing to outsiders. It is not meant to be eaten alone but acts as the perfect vehicle for an array of vibrant, flavorful soups and stews. Made from a combination of boiled starchy vegetables like cassava, yams, or plantains that are pounded relentlessly in a large mortar with a pestle, its creation is an art form, often accompanied by a rhythmic, musical pounding that is a familiar sound in many households. The result is a smooth, dense, and slightly elastic dough that is formed into neat balls.

The true magic of Fufu is revealed in the eating, which is a deeply cultural and tactile experience. Traditionally, and in most social settings, it is eaten with the hands.A small piece is torn off the main ball, indented with the thumb to form a small scoop, and then used to soak up rich, often spicy, soups like Ghanaian Groundnut Soup, Nigerian Egusi, or Nigerian Ogbono. The fufu itself has a very mild, slightly sour flavor (especially when made with fermented cassava), which provides a neutral, starchy base that perfectly complements and tempers the intense flavors and heat of the accompanying soup. Its smooth, soft texture is incredibly soothing.

Nutritionally, Fufu is primarily a source of complex carbohydrates, providing sustained energy. The specific nutrients depend on its base ingredient; cassava fufu is high in vitamin C and calcium, while yam fufu provides potassium and vitamin B6. Its real nutritional value comes from the stew it is paired with, which is typically loaded with proteins (fish, meat, chicken), healthy fats (palm oil, groundnuts), and a variety of vegetables and leafy greens, creating a perfectly balanced meal. It is filling, economical, and designed for communal dining, encouraging sharing and conversation around a single pot.

What many people may not know is the sheer physical effort required to make traditional fufu, with the pounding process being a test of strength and endurance. This has led to the popularization of modern “instant fufu” powders, which simply require mixing with hot water, making the dish accessible to the global diaspora. Furthermore, the specific type of fufu varies greatly by region: in East Africa, a similar dish called Ugali is made from maize flour and has a firmer consistency; in the Caribbean, a version called “fufú” is made from plantains. For a tourist, learning to eat fufu with your hands is a rite of passage, a direct and intimate connection to the heart of West African social and culinary life.

7. Chikwangue / Cassava Bread (Central Africa)

A vital staple in the heart of Central Africa, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo-Brazzaville, and Cameroon, Chikwangue (also known as Kwanga or Bobolo) is a fermented cassava dough that presents itself in a most unassuming way. Wrapped tightly in large leaves into a firm, cylindrical parcel, it can look, to an uninformed eye, like a strange, inedible package. However, inside this natural packaging lies a food that is central to the diet of millions. Its preparation is a days-long process involving soaking cassava roots in water to ferment, after which the pulp is grated, squeezed dry of its toxic cyanogenic compounds, and then cooked into a thick paste before being wrapped and steamed or boiled.

The texture and taste of Chikwangue are its defining characteristics. It has a dense, firm, and pleasantly chewy, almost rubbery consistency that requires some effort to bite into. Its flavor is distinctly sour and tangy, a direct result of the lactic acid fermentation it undergoes. This sourness makes it an excellent counterpoint to the rich, often oily, and intensely flavorful stews, sauces, and grilled fish or meat it is always served with. It is not a bread in the soft, leavened Western sense, but a starch meant to be torn by hand and used to scoop up sauces, much like fufu. Its unique texture allows it to hold together well without disintegrating in liquid.

Nutritionally, Chikwangue is a resilient and practical food source. The fermentation process not only develops its signature flavor but also preserves it, allowing it to last for several days or even weeks without refrigeration, a crucial advantage in tropical climates with limited infrastructure. While it is predominantly a source of carbohydrates, the fermentation enhances its nutritional profile by increasing the bioavailability of certain amino acids and B vitamins. It is a food born of necessity and ingenuity, transforming the potentially toxic raw cassava into a safe, durable, and filling staple.

What people likely don’t know is the incredible social and economic network behind Chikwangue. Its production is often a specialized trade, with women-dominated cooperatives responsible for the labor-intensive process from harvesting the cassava to the final packaging and sale. The leaf-wrapped bundles are a common sight in markets and on the heads of street vendors, and they are a ubiquitous provision for long journeys on the Congo River. For a visitor to Central Africa, trying Chikwangue is to taste a food that is literally woven into the fabric of daily life, a preserved, portable, and powerfully flavored starch that fuels the vibrant, resilient heart of the continent.

6. Cow-Foot Soup (West Africa)

A beloved delicacy in West African countries like Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone, Cow-Foot Soup is a dish that truly tests the “don’t knock it ’til you try it” adage. Its appearance can be initially challenging: the cooked cow’s feet, or “cow heel,” release vast amounts of collagen and gelatin, creating a broththat is thick, viscous, and often described as “slimy” or “slippery.” The pieces of foot themselves, with their distinctive texture of skin, tendon, and cartilage, can also be visually intimidating for those unfamiliar with offal-based cuisines. However, this initial shock is the very prelude to its deep, comforting appeal.

The magic of this soup lies in its slow, patient preparation. The cow feet are meticulously cleaned, scrubbed, and then boiled for hours until they are fall-off-the-bone tender and have imparted all their richness into the stock. This long cooking process breaks down the tough connective tissues into a soft, gelatinous, and melt-in-the-mouth texture that is deeply satisfying to chew. The broth is then elevated with a robust blend of West African spices, scotch bonnet peppers for heat, onions, garlic, ginger, and local seasonings like utazi or scent leaves, which add a pleasant, slightly bitter contrast to the rich, savory base.

From a nutritional perspective, Cow-Foot Soup is a powerhouse of beneficial compounds. It is exceptionally rich in collagen and gelatin, which are renowned for promoting joint health, skin elasticity, and gut health. It is also a good source of protein, minerals like calcium and phosphorus, and healthy fats. In many cultures, it is considered a restorative food, often given to new mothers or those recovering from illness to help rebuild strength and vitality. It is more than just a meal; it is a form of traditional, food-based medicine.

What many people may not know is the social status often associated with this dish. While it is an affordable meal for many, it is also considered a special treat, often served at celebrations and gatherings to honor guests. The skill lies in cooking it to the perfect texture where the cartilage is tender but not disintegrated, providing a unique mouthfeel that is cherished by aficionados. For the adventurous eater, embracing a bowl of Cow-Foot Soup is an initiation into the West African philosophy of nose-to-tail eating, where every part of the animal is valued and transformed, through culinary skill and time, into a dish of surprising depth and deliciousness.

5. Injera (Ethiopia & Eritrea)

Injera is more than just a bread; it is the centerpiece of Ethiopian and Eritrean cuisine, a culinary canvas, and an edible utensil all in one. To first-time observers, its appearance can be puzzling: this large, spongy, crepe-like flatbread, covered in what looks like tiny pores, has a pronounced sour aroma and a greyish-tan color. Made from teff flour, an ancient and tiny grain native to the Horn of Africa, injera’s unique characteristics come from a fermentation process that can last several days. This fermentation gives it its signature tangy flavor and airy, slightly elastic texture.

The proper way to eat injera is a communal and hands-on experience that delights visitors once they participate. A large, single piece of injera is laid out on a platter, and an array of colorful stews and salads, known as “wats” and “tibs,” are spooned directly onto it. Diners then tear off smaller pieces of additional rolled injera and use them to scoop up the various dishes, all sharing from the central platter. The injera soaks up the flavorful sauces, and its sourness provides a perfect counterbalance to the rich, spicy, and often complex flavors of the stews, which can be based on beef, lamb, chicken, lentils, or split peas.

Nutritionally, injera is a superfood in its own right. Teff is one of the smallest grains in the world, but it is nutritionally dense, packed with iron, calcium, protein, and fiber. It is also naturally gluten-free. The fermentation process not only develops its unique taste but also increases the bioavailability of its iron and other minerals, making it an exceptionally healthy staple. A meal centered on injera is not only flavorful but also incredibly balanced and nourishing, providing sustained energy from complex carbohydrates and a wide range of micronutrients.

What people likely don’t know is the incredible skill required to make a perfect injera. The fermented batter must have just the right consistency, and it is poured in a swift, spiral motion onto a large, hot clay plate called a “mitad” to cook without a lid, which creates the distinctive steam holes on top. The best injera is soft, flexible, and has a delicate, slightly bubbly texture without being soggy. For tourists, the first meal eaten from a shared injera platter, or “gebeta,” is often a profound cultural revelation, a delicious, interactive, and communal way of dining that embodies the warm, social spirit of the Ethiopian and Eritrean people.

4. Kachumbari With Snails (East Africa)

In the culinary landscape of East Africa, particularly in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, a dish that beautifully marries the familiar with the exotic is Kachumbari with Snails. Kachumbari itself is a fresh, vibrant, and simple salad akin to pico de gallo, made from finely chopped tomatoes, onions, cilantro, and chili peppers, often with a squeeze of lime juice. It is a refreshing and well-known side dish. The shock factor comes when it is served as an accompaniment to a heap of tender, cooked land snails, their coiled shells and soft, greyish bodies presenting a textural and visual challenge for those unaccustomed to eating escargot.

The preparation of the snails is crucial to their deliciousness. After being purged to clean their systems, the snails are boiled, removed from their shells, and then simmered in a flavorful broth with a blend of East African spices, typically including garlic, ginger, turmeric, and a generous amount of curry powder, which gives them a vibrant yellow hue and an aromatic, savory flavor. The slimy texture feared by many is transformed through cooking into a tender, slightly chewy morsel that absorbs the rich spices beautifully. Served alongside the cool, crisp, and acidic Kachumbari, the combination is a masterful balance of flavors and textures.

Nutritionally, this dish offers a well-rounded profile. Snails are an excellent source of lean protein, are very low in fat, and are rich in essential minerals like iron, magnesium, and selenium. The Kachumbari provides a wealth of vitamins A and C from the tomatoes and cilantro, as well as antioxidants and hydration. Together, they create a meal that is light yet satisfying, packed with micronutrients, and representative of a “farm-to-table” ethos, as snails are often foraged from the wild.

What many people may not know is that snail consumption in East Africa is not a novelty but a traditional practice, especially within certain communities where they are considered a seasonal delicacy. They are often collected after the rains when they emerge from the soil. The curry-style preparation is a testament to the historical Indian influence on Swahili coast cuisine. For a tourist, trying this dish is a two-part adventure: first, overcoming the initial visual hurdle, and second, being rewarded with the discovery of a spiced, savory delicacy that, when paired with the fresh salad, offers a uniquely East African taste of the land.

3. Egusi Soup (Nigeria & West Africa)

A cornerstone of West African cuisine, particularly in Nigeria and Ghana, Egusi Soup is a dish that often confuses tourists with its thick, grainy, and somewhat pasty appearance. Its distinctive texture comes from its primary ingredient: egusi, which are the seeds of certain melons (like watermelon) that have been dried, shelled, and ground into a powder or paste. When added to broth, the ground seeds swell and thicken the soup to a consistency that can resemble a thick, lumpy porridge or a savory paste. However, to judge it by its looks alone is to miss out on one of the most flavorful and comforting dishes in the region.

The depth of flavor in a well-made Egusi Soup is immense. The ground melon seeds themselves have a rich, nutty flavor that forms the soup’s base. This is built upon with a base of red palm oil, which gives the soup its characteristic reddish hue and an earthy, unique flavor. Into this, a rich stock is added, along with an assortment of meats (beef, goat, or tripe), fish (dried stockfish and crayfish are essential for their umami punch), and leafy vegetables like bitterleaf or spinach, which add a contrasting texture and a slight bitterness. The soup is generously spiced with Scotch bonnet peppers and traditional seasonings, resulting in a complex, hearty, and deeply savory stew.

Nutritionally, Egusi Soup is a complete and balanced meal. The melon seeds are exceptionally nutritious, packed with protein, healthy fats (including essential fatty acids), and minerals like magnesium, zinc, and iron. The addition of various meats and fish provides additional protein, while the leafy greens contribute vitamins and fiber. The red palm oil is rich in antioxidants, particularly vitamin E. It is a dish designed to provide sustenance and energy, often eaten with a heavy starch like fufu, pounded yam, or eba to create a filling and nutritious meal.

What people likely don’t know is the vast regional and even familial variation in Egusi Soup preparation. Some versions are “fried,” where the egusi paste is sautéed in palm oil before liquid is added, creating a firmer, clumpier texture. Others are more brothy. The choice of leafy vegetable can dramatically alter the flavor profile. Furthermore, the egusi seed is so versatile that it can also be used to make a kind of “melon seed burger” or steamed pudding. For a visitor, a first spoonful of Egusi Soup is a revelation—a nutty, spicy, and deeply aromatic experience that showcases the incredible ability of West African cooks to create profound deliciousness from simple, locally-sourced ingredients.

2. Samp and Beans (South Africa)

A classic and beloved comfort food in South Africa, Samp and Beans (often called “Umngqusho” in isiXhosa) is a humble dish whose appearance can be deceiving. It consists of crushed, dried maize kernels (samp) and sugar beans (a type of small white bean) slow-cooked together until they form a thick, hearty, and somewhat sticky porridge. Its lumpy, beige, and monochromatic look might not win any beauty contests in the eyes of a tourist, but its taste is the very definition of soul food, simple, satisfying, and deeply flavorful, evoking a sense of home for millions of South Africans.

The preparation of Samp and Beans is a lesson in patience and the alchemy of slow cooking. The dried samp and beans are typically soaked overnight to reduce cooking time, then simmered for several hours with nothing more than an onion, salt, and perhaps a knob of butter or a splash of oil until the grains and beans are tender and have melded together. The magic often happens at the end, when a rich, fried tomato and onion sauce is sometimes stirred through, or a meaty bone is added during cooking to impart a savory depth. The resulting texture is soft and creamy, with a pleasant chew from the samp, and the flavor is earthy, starchy, and comforting.

This dish is not just food; it is a plate of history and cultural significance. It is a traditional staple of the Nguni people (Xhosa and Zulu) and was famously declared by the late South African President Nelson Mandela as one of his favorite foods, symbolizing the food of his childhood in the Eastern Cape. Nutritionally, it is a powerhouse. The combination of maize and beans creates a complete protein, providing all the essential amino acids, making it an excellent and affordable source of nutrition. It is also high in complex carbohydrates for energy and dietary fiber for digestive health.

What many people may not know is that “samp” is derived from the Narragansett Native American word “nasàump,” showing the cross-cultural exchange of food staples. In South Africa, it is a dish that transcends economic boundaries, enjoyed by people from all walks of life. It can be a simple, budget-friendly meal or be elevated with the addition of lamb, potatoes, or a variety of spices. For a tourist, trying a bowl of authentically prepared Samp and Beans is to taste a piece of South Africa’s soul—a dish that speaks of resilience, community, and the profound comfort found in the most basic of ingredients.

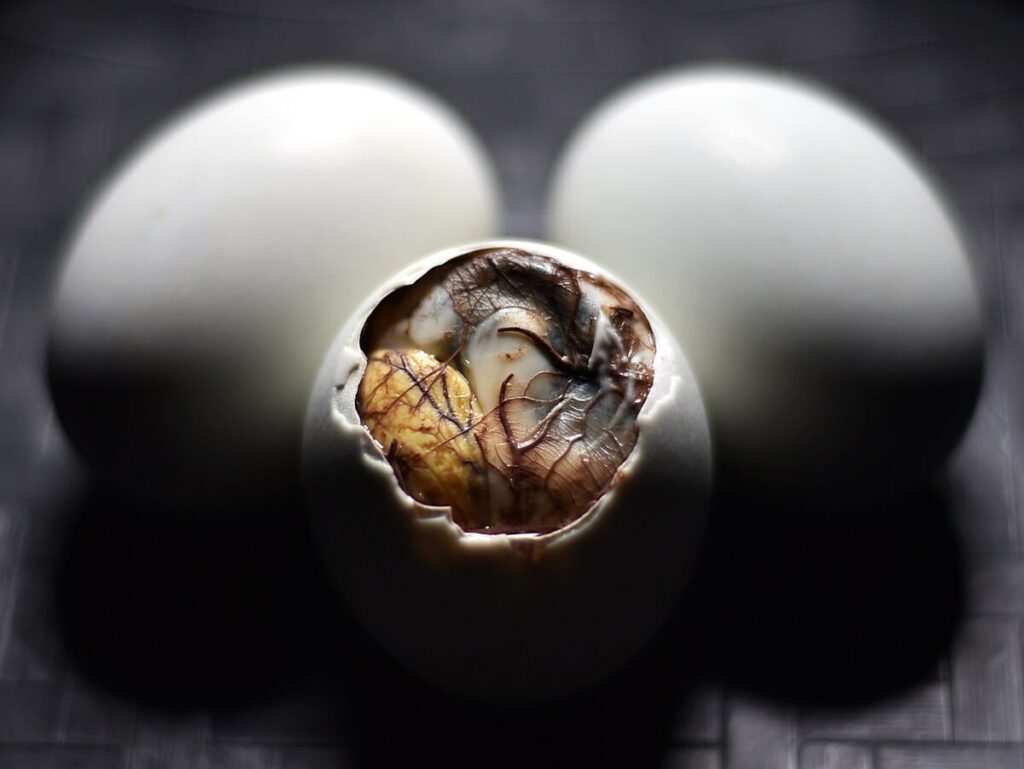

1. Balut (Found in some North African and Saharan Cuisines)

While balut is famously associated with Southeast Asia, a similar tradition of consuming fertilized duck eggs exists in parts of North Africa, particularly in Algeria and Egypt, where it is known as “Bayd al-Batt” or simply referred to as a local delicacy.The sight of this snack is arguably its biggest hurdle: a partially developed duck embryo, complete with visible beak, feathers, and bones, nestled inside the egg. This can be profoundly shocking, even alarming, for the uninitiated. However, for those who grew up with it, it is a cherished, protein-rich treat, often enjoyed with a sprinkle of salt and a dash of spice.

The preparation is simple yet precise. The fertilized eggs are incubated for a specific period, typically between 14 to 21 days, to reach the desired stage of development where the embryo is formed but still tender. They are then boiled or steamed, similar to a hard-boiled egg. To eat it, one typically cracks open the top of the eggshell, sips the savory broth inside, and then consumes the contents, which include the rich, creamy yolk and the tender, slightly gamey embryo. The texture is a complex combination of creamy, firm, and gelatinous, while the flavor is deeply savory and rich, often described as a more intense version of chicken soup.

Nutritionally, balut is considered a potent food. It is incredibly high in protein and calcium (from the developing bones), and is also a good source of phosphorus and vitamins A and E. In the cultures where it is consumed, it is often believed to be an aphrodisiac and a restorative food, providing strength and vitality. It is commonly sold by street vendors in the evening and is a popular snack to enjoy with friends, often accompanied by a cold drink to balance its richness.

What people likely don’t know about its North African context is its seasonal and cultural niche. It is not an everyday food for most but a seasonal specialty, often consumed during the colder months for its perceived warming properties. Its consumption connects to a broader global tradition of valuing fertilized eggs, from the Filipino balut to the Chinese “maodan.” For the most adventurous of culinary tourists, trying balut is the ultimate test of gastronomic bravery. Overcoming the initial visual and psychological barrier often leads to the realization that it is, at its core, a uniquely textured and deeply flavorful embodiment of a very particular and ancient culinary courage.

We welcome your feedback. Kindly direct any comments or observations regarding this article to our Editor-in-Chief at[email protected], with a copy to[email protected].

https://www.africanexponent.com/top-10-african-foods-that-shock-tourists-but-tastes-delicious-than-they-look/