On an evening in mid-January, there were bouquets piled outside of Linda Lavin’s trailer on the Disney lot in Burbank, Calif. Nearby, on a soundstage, a black ribbon was wrapped around her caricature.

Lavin had died on Dec. 29, at age 87. Now the creators and cast of “Mid-Century Modern,” a Hulu sitcom that shoots in front of a live studio audience, had returned to work to honor her. That night, they would film a half-hour episode designed to pay tribute to her character, Sibyl Schneiderman, while also eulogizing an actress with an outstanding seven-decade career.

That was hard enough. Even harder: They had to make it funny.

“The job is to make sure it doesn’t get too sad and too sentimental,” said James Burrows, the multicamera-sitcom legend who directed the episode. “You have to remember it’s a comedy, and you’ve got to make the audience laugh.”

I had reached out to the sitcom’s creators back in the fall. A new sitcom set among gay men in later life — think “Golden Girls” for the marriage equality set — it sounded like a hoot. It also offered a chance to explore how depictions of queer relationships have changed since the 1990s.

But when Lavin died unexpectedly after most of the season had been shot, an irreverent sitcom with an impressive zingers-per-minute rate suddenly had to pivot. So the reporting assignment pivoted, too. (All 10 episodes arrived on Friday.)

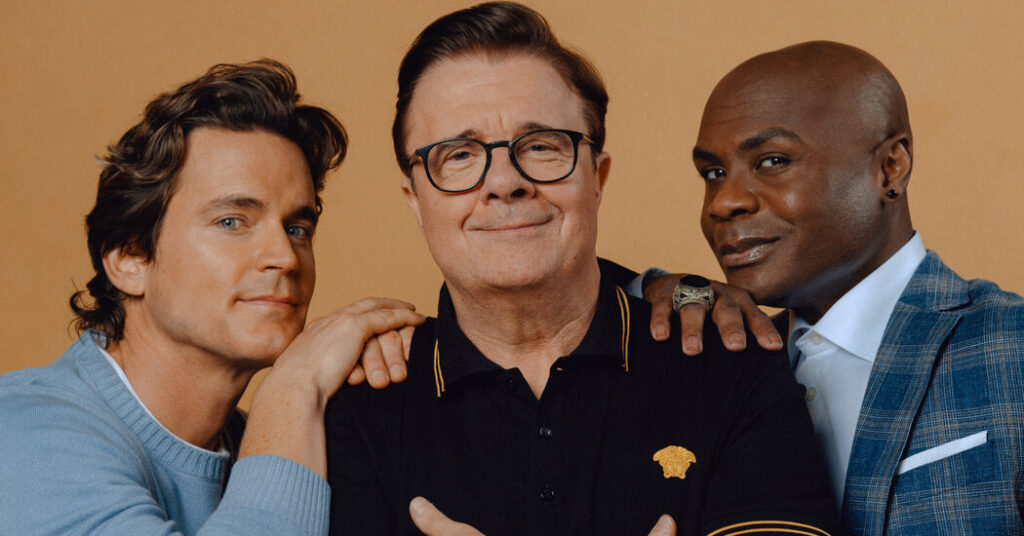

Last summer, Hulu agreed to fund a new pilot from the creators of “Will & Grace,” David Kohan and Max Mutchnick. Set in Palm Springs, Calif., it centered on three roommates, to be played by Nathan Lane, Matt Bomer and Nathan Lee Graham. As in “The Golden Girls,” Kohan and Mutchnick knew they wanted a mother character, Sibyl, to join the roommates.

They considered several actresses for the Sibyl role, including Lavin, a Tony winner for “Broadway Bound” and a star of the seminal 1970s sitcom “Alice.” (Mutchnick and Kohan knew her best from the “Will and Grace” spinoff “Sean Saves the World,” in which she had played Sean Hayes’s mother.) Burrows insisted they hire her.

“That woman is a heat-seeking missile for a joke,” he remembered telling them.

The creators invited her to a video call last year to discuss the role. Lavin joined them from Berlin, where she was vacationing. “She was such a cool, spunky chick,” Mutchnick said. Lavin told them she would play Sibyl if certain conditions were met. The character, the mother of Lane’s Bunny, was conceived of as an Iris Apfel-type with short white hair. Lavin objected.

“‘When you see how fantastic my hair is and what kind of shape I’m in, you’re not going to want me to look like an old lady,’” Mutchnick recalled her saying.

On set, she bonded quickly with her castmates. “She was very disarming,” Graham said. “She just made you feel like, Let’s play.” And she was an unfailingly good sport, even lip syncing the Salt-N-Pepa song “Whatta Man” in the pilot.

“She was 87, wearing heels and walking around like she was 37,” Burrows said.

It was easy to write for Lavin’s Sibyl. Lane’s character quips that her bedroom “smells like Nivea and disapproval” and that Sibyl will probably live to 200 on cottage cheese and spite alone. When it came to her own lines, Lavin nailed them in just a take or two, imbuing grace and heart into even the meanest jibe, seemingly without effort.

“She was just always so grounded and real in a medium in which you can be encouraged to be over the top,” Bomer said.

In December, a few months into filming, Lavin told the showrunners that she was ill. But her prognosis was excellent, she assured them, and she would soon begin treatment. In the event that she couldn’t film, she invited to them to write her illness into the script.

Her death, at the end of the month, was sudden and unexpected. When Lane received the call, he couldn’t make sense of it. “What?” he recalled asking Mutchnick, again and again. He was sure he had misheard.

The showrunners visited with Lavin’s husband, Steve Bakunas, an actor and musician, who described to them her last moments, in the car on the way to a hospital. But even as Kohan and Mutchnick grieved, they had already decided to address the death in an episode. It would be best for them, they reasoned, best for the audience, best for the show.

“You have to tell the truth, and then you have to show this world moving forward,” Mutchnick said later. To hew close to that truth, they went back to Bakunas to ask if they could include a version of that final conversation in the script.

Once that first grief had ebbed, the terror came in. “The big fear was, Are we going to be up to the gravity of the moment?” Kohan said. “Because we wanted so badly to honor this woman that we all loved.”

“But we didn’t want to get into an area that was schmaltzy,” Mutchnick added.

Burrows gave them some advice. The show should be a kind of sandwich. Hard comedy at the top, sentiment squeezed into the middle, a turn back toward comedy at the end.

“Linda was a sitcom person,” Mutchnick said. “That’s the way we honored her.”

The actors were on board. Lavin was an old-school trouper. They felt it was what she would have wanted.

“I was emotionally bereft,” Graham said. “But Linda was a real old time go-getter; she was a broad, a full-on broad. Her attitude would have been: This has happened. It sucks. But we’ve got to do it, and we’ve got to do it really, really well.”

Rehearsals that week felt strange. Bomer had the sense that they were merely marking their lines, not ready yet to let the feelings out. Bakunas had given each of the actors a piece of Lavin’s jewelry, which they put in their dressing rooms or in their pockets as totems.

By Wednesday, when I joined the cast and crew on the soundstage, it was time to tape the episode, the season’s ninth. The feeling in the room, even as the warm-up comedian joked with the audience, was, Lane said later, overwhelmingly emotional. The showrunners set up a kind of protective barrier around Lane, who as Bunny would have to shoulder the sad parts.

“We tried extra specially hard to make sure people were not in his sightline, that he was just in the world of the character who had just lost his mother,” Mutchnick said.

After a jaunty opening scene that involved a Tupperware cascade, a much more somber scene followed, in which Lane’s Bunny recounted Sibyl’s death, how even as he was driving her to the hospital she kept telling him to slow down.

“Sibyl died,” the scene began. “She’s dead. My mother’s dead.” Between takes he wiped away his tears. Burrows put an arm around him. “OK, honey,” he said. “Take your time.” Lane reached into his pocket and touched Lavin’s brooch. Then he took the scene again.

The taping ended with a screened montage of Lavin in previous episodes and then a video she had sent to Dan Bucatinsky, one of the writers on the show, in which she sits at a piano and sings the 1939 ballad “We’ll Meet Again.” Some audience members teared up. The cast felt similarly moved.

“So much of the material has been some of the closest to the bone of anything I’ve ever worked on,” Bomer said later. “I did not expect that signing up for a half-hour comedy.”

A comedy about men in retirement, particularly one that begins with the funeral of a different character, was always going to be at least a little about death. But no one expected it to come so soon or with such intensity.

“We were saying goodbye to her,” Mutchnick said, and Lavin’s colleagues were trying to do it in the way she would have wanted — with laughs and heart.

“It was a true love letter to Linda,” Bomer said. “I feel we really honored her in a beautiful way. But I obviously don’t ever want to have to do that again.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/28/arts/television/mid-century-modern-linda-lavin-hulu.html