This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Greetings from New York. I have just returned from Boston, where the mighty Harvard University has been staging its inaugural Climate Action Week in recent days. As Jeremy Grantham, the investment luminary who has long shouted (or thundered) about the risks of climate change, observed in a panel that I moderated, Harvard has been lamentably slow to embrace these issues. But the Salata family, which has been wildly successful in private capital, has now funded the creation of a brand new climate centre, and a number of other big, deep-pocketed Harvard alumni, such as investor John Fisher, have chipped in too.

The creation of the university’s cross departmental Climate Action Week is no mean feat, given that Harvard is so prone to tribalism between departmental silos. And the institution is such a big brand name that the event highlights a bigger point about the current zeitgeist in corporate America: irrespective of the rightwing backlash against environmental, social and governance issues, incumbent companies, start-ups and investors alike are increasingly focused on climate today. This is particularly true since the introduction of the Inflation Reduction Act which is creating rich opportunities in green energy.

A report below, from the Lazard investment bank, echoes this point: US climate disclosures are also rising, even as company directors are now engaged in “green-hushing” (ie they avoid talking about ESG out of fear of the political risks). However, the picture is patchy: check out our report below on the conflicts that some corporate directors are quietly juggling in this respect. And, as ever, let us know what you think. (Gillian Tett)

The bank directors with ‘red flag’ fossil fuel jobs

As investors at shareholder meetings in recent weeks scrutinised bank directors’ abilities to manage risk and deliver returns, one striking fact may have gone unnoticed.

Non-executive directors at some of the world’s biggest financial institutions also have top roles at oil and gas or power companies, according to data compiled by the investigative website DeSmog and analysed by Moral Money.

Take Bank of America. Denise L Ramos, a director on its sustainability committee, has a surprising side gig: chair of the public policy and sustainability committee at Texan oil refiner Phillips 66. The refiner was among the 20 most obstructive companies on climate change last year, according to InfluenceMap’s lobbying record analysis. The bank declined to comment.

A few other examples stand out. Adebayo Ogunlesi — the chair of Goldman Sachs’s governance committee, which helps manage the bank’s exposure to climate change — is also head of the committee that oversees pay at Kosmos Energy, a Texan deepwater oil exploration company. His colleague Jessica Uhl, a director on Goldman Sachs’s audit, risk and governance committees, worked at Shell for nearly two decades — including as chief financial officer — before joining the bank last year.

Wells Fargo director Theodore F Craver Jr, former boss of the utility Edison International, is also chair of the governance committee at US power company Duke Energy, which says it generates more than a quarter of its energy from coal. Morgan Stanley has boardroom links to the oil and gas industry too; director Rayford Wilkins Jr is a sitting board member of Texas-based oil refining company Valero Energy.

Tom Sanzillo, director of financial analysis at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, told Moral Money that banks commonly hire directors from industry to deepen relationships with clients and improve their understanding of the space.

But having a number of directors with interests in highly polluting companies could be a “red flag”, Sanzillo said. Directors could “push banks to be in favour of fossil fuels at a time when there shouldn’t be major interest from a financial point of view”, and “undercut” policies that move money into competitor industries like wind, solar and electric cars.

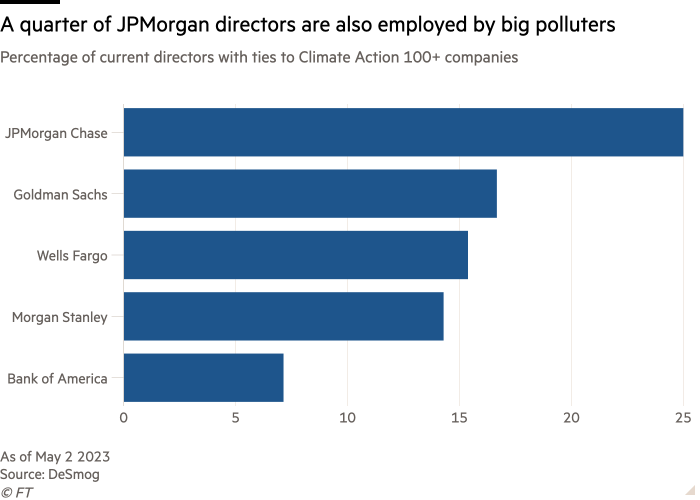

On average, around one in every seven directors at Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan has ties to a company identified by Climate Action 100+ as a top global polluter, for example in aviation, steel, coal mining or oil and gas. This includes working as a director, chief executive or investment officer.

The more senior the position on a bank’s board, the more concerning the crossover, Sanzillo added.

“It’s an ethical question. All things considered, you have to test it with your gut.”

Bank directors serving on the board of unconnected industrial companies is not “inherently wrong”, and can bring “beneficial insight to both sides”, said Roger Barker, director of policy and governance at the UK’s Institute of Directors.

But to mitigate reputational risk, directors in such a position should “adopt an independent perspective and work hard to exert a positive impact on the sustainability profile of the polluter,” Barker added.

Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan have all pledged to reduce emissions from their lending and investment portfolio to net zero by 2050 through membership of the Net Zero Banking Alliance.

And according to data from the Rainforest Action Network, these banks have cut their lending and underwriting of debt and equity issuances to oil, gas and coal companies by nearly a third in just a year; they extended a combined $133.1bn last year, compared with $196.4bn in 2021.

JPMorgan said in response to these figures that it provides financing across the energy sector, “supporting energy security, helping clients accelerate their low carbon transition and increasing clean energy financing with a target of $1tn for green initiatives by 2030.”

The relationship between banks and the energy sector is shrinking but still large, making directors’ second jobs “shocking” but “not surprising”, said Caleb Schwartz, a research and policy analyst at RAN.

The practice is also common in Europe. The head of Barclays’s remuneration committee, Brian Gilvary, was formerly the chief financial officer at BP and now serves as non-executive chair of Ineos Energy, which said earlier this year that it was acquiring thousands of Texan oil wells. Amanda Blanc, chief executive of the insurer Aviva, is a non-executive director at BP. Blanc has no oversight of investment decisions by the group’s asset manager, Aviva Investors.

And DeSmog’s investigation also raises concerns about biodiversity risk. JPMorgan’s Virginia M Rometty, a member of the bank’s governance committee, sits on the board of Cargill, the agribusiness giant facing a legal complaint over Amazon deforestation. The bank has participated in an estimated $7.3bn-worth of Cargill bond and loan deals over the past decade, according to supply chain transparency group Trase.

Barclays said: “Our non-executive directors are chosen for the experience and insight they are able to bring to their roles”, including oversight of the bank’s goal to “be net zero by 2050”.

Wells Fargo said its board members are “highly qualified individuals from diverse backgrounds who have the leadership, executive management, financial, industry, and other expertise to act in the best interests of our company and its shareholders.”

Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Aviva declined to comment. JPMorgan declined to comment on its directors.

The directors did not respond to requests for comment through the banks and through Ineos Energy. (Kenza Bryan)

Investors show preference for companies that disclose emissions

Whether they are sustainable investors or not, shareholders seem to be growing leery of companies that fail to disclose their carbon emissions, according to Wall Street firm Lazard.

In a new report, Lazard found that companies in the Russell 3000 index that report emissions tended to have lower price-to-earnings ratios than peers that don’t. Only about one-sixth of the Russell 3000 companies are voluntarily disclosing their emissions.

The research found no similar correlation between company valuations and promises of emission cuts. This suggests that companies will be rewarded for increased transparency — even if they are reporting ugly emission figures.

“We found that disclosures matter, but commitments don’t,” Peter Orszag, head of financial advisory at Lazard, told me. Orszag was previously director of the US Office of Management and Budget under the Obama administration.

“Without disclosures, investors assume the worst and they may apply an even larger discount” to the share price, he said. “The general atmosphere is one in which investors will look at [pledges to cut emissions] as largely rhetorical.”

There was a particularly strong link between carbon disclosures and stock valuation at industrial companies and utilities, the research found.

Ultimately, corporate laggards on carbon emissions disclosures will be pulled into the daylight by the Securities and Exchange Commission when the agency adopts climate disclosures at some point this year.

The rules would require companies to disclose scope 1 and 2 emissions, as well as scope 3 emissions in certain high-polluting industries.

But until then, investors remain in the dark about corporate emissions and their risks. Investors are likely to continue discounting the risks they cannot see. (Patrick Temple-West)

Smart reads

Moral Money Summit Europe

Join us in London, or online, for the third annual Moral Money Summit Europe on May 23-24. Leading investors, corporates and policymakers will come together to discuss what needs to happen next to unlock a more sustainable, equitable and inclusive economy.

Recommended newsletters for you

FT Asset Management — The inside story on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar industry. Sign up here

Energy Source — Essential energy news, analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here