Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Three decades ago I became fascinated by the concept of “social silence” — or the idea advanced by intellectuals such as Pierre Bourdieu that what we do not talk about is more important than what we do.

Right now this silence hangs heavily over the markets. This week there has been a cacophony of terrifying noise around geopolitical events — epitomised by President Donald Trump’s warning that America “may or may not” join Israel’s attacks on Iran.

And gloomy economic data keeps on tumbling out. Last week, the World Bank slashed its prediction for global growth (to 2.3 per cent) and America (to 1.4 per cent) — warning that if the 90-day pause of Trump’s so-called “liberation day” tariffs expires on July 31, we will see “global trade seizing up in the second half of this year”. This week the Federal Reserve also sharply downgraded its US growth projection and raised its inflation forecast. This amounts to stagflation-lite.

Yet US equity markets have quietly crept up in recent weeks, rising by more than 20 per cent since early April — recovering from the moment they swooned after the “liberation day” tariff announcement. Indeed, they are close to record highs. And while 10-year bond yields, at 4.4 per cent, are almost a percentage point higher than their levels last autumn, these have recently stabilised as well — even as US fiscal projections deteriorate.

So the big market “silence” today is not expressions of escalating risk but the seeming lack of investor panic thus far.

What’s behind this reticence? One explanation might lie in what my colleague Robert Armstrong has called the “Taco” effect — the presumption that Trump Always Chickens Out on his threats. Another is a second “T” problem: time lags.

The Danish central bank, for example, recently studied how equity markets have reacted to trade shocks since 1990. The research concluded that while “trade policy uncertainty [has] significant negative effects on economic activity . . . it takes up to a year for the effects to materialise”.

Similarly, the Bank for International Settlements warned last week that we faced “a substantial negative contribution of uncertainty to both investment and output growth”. However, it calculates that the biggest impact on investment will occur in 2026 — note, not this year — to the tune of a 2 per cent lower rate of capital expenditure in the US and Japan next year.

Separately, a slew of research has emerged that shows the degree to which Trump’s threats to deport millions of undocumented workers could hurt the American economy. While raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement are grabbing headlines right now, the real economic impact will not be seen for a couple of years. To cite one example: the Peterson Institute reckons that if 1.3mn migrants were deported, this would cut GDP by “just” 0.2 per cent this year — but by 1.2 per cent in 2028. Hence the time-lag problem.

In addition to this, there is a third possible explanation for the lack of panic right now: disaster fatigue. More specifically, investors face such an overload of disorienting shocks that they have (at best) become well adapted to handling pain, without panic, or (at worst) are so stunned that they cannot process it.

Call this, if you like, the “death by a thousand cuts” problem. Right now, there is no single shock that is clearly big enough to spark a market crash. Yes, if oil jumps above $100 a barrel amid a further escalation of the Middle East war and closure of the Strait of Hormuz, this would certainly hurt. And that scenario cannot be discounted — least of all, according to Philip Verleger, an energy economist, because when Israel’s initial attack on Iran began “oil industry firms were caught with low inventories” and there were “very large call positions” (ie derivative bets) that could unwind.

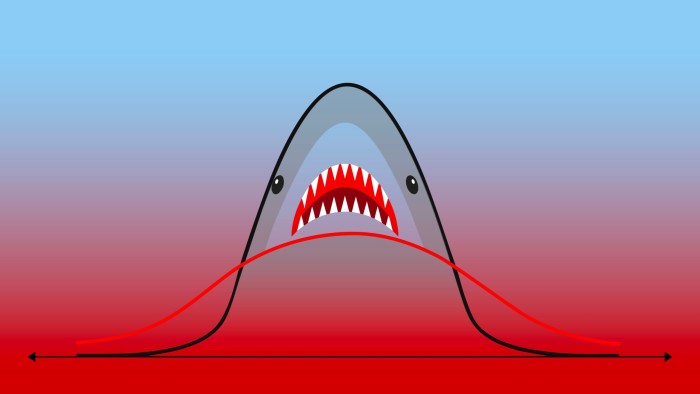

But so far oil prices are “just” $75 or so a barrel. What investors face today is a looming tail risk rather than an imminent, tangible disaster. Or to use another analogy: markets are not grappling with a single “heart attack” shock (as during the Covid-19 pandemic) but a spreading economic cancer, in the form of metastasising uncertainty around future hurt. This is not 2020.

Hence the brief explosions of market volatility — as measured by the VIX index — which then die down. This is also the reason why the message from different asset classes is not consistent. “US equities are behaving like Trump, chasing short-term wins,” says Jack Ablin, chief investment officer of Cresset. “Long bonds are acting like [Elon] Musk, fixated on longer-term, uncomfortable truths.”

And here we come back to the problem of social silence. As investors try to parse the confusing tail risks, most are beset with profound doubts — and to a degree that leaves even professionals feeling nervous if not embarrassed. That means it might not take much for equity markets to crack; but it also means that no one knows when (or if) this might occur. Sometimes it is indeed the silence that screams loudest of all.

gillian.tett@ft.com

https://www.ft.com/content/cbead7d6-861b-4721-8c0a-703f32effd91