Credit Suisse may be gone but it is far from forgotten. London’s High Court is the latest venue to unearth failings at the venerable Swiss bank before its emergency takeover in 2023 by arch-rival UBS.

London’s Rolls Building is where a $440mn legal battle is being waged between a Credit Suisse investment fund, SoftBank, and a subsidiary of Greensill Capital, the group founded by Australian financier Lex Greensill. The fund brought the lawsuit in an attempt to recover hundreds of millions of dollars that it says investors lost following the 2021 collapse of Greensill, which was in turn backed by SoftBank.

Greensill’s implosion caused Credit Suisse to suspend and close $10bn worth of funds that had lent money via the supply-chain finance business, trapping the savings of more than 1,000 of the Swiss bank’s most prized clients.

Mr Justice Miles, the judge presiding over the four-week trial, ordered the release on Wednesday of a report prepared for Swiss regulator Finma by an external law firm. He also ordered the release of a copy of Finma’s subsequent ruling on Credit Suisse’s relationship with Greensill, after requests from the Financial Times and other media organisations. Excerpts of the 500-page files have been presented as evidence in the trial.

The previously confidential Finma files reveal new information over the nature of Credit Suisse’s relationship with Greensill, as well as the cultural failings UBS must contend with as it continues to integrate the two lenders.

Here are the highlights.

Secrets and lies

Credit Suisse’s relationship with Lex Greensill caused “immense reputational damage” to the now defunct bank, with its executives “naively” relying on information they received from the Australian financier to defend the partnership, according to Switzerland’s financial regulator.

Finma said the bank failed to act on warnings it received about Greensill Capital and at times obstructed investigators during its probe.

The watchdog said that enquiries to Credit Suisse regarding allegations against metals magnate Sanjeev Gupta and Greensill were “sometimes answered incompletely, misleadingly or incorrectly” by the bank.

“Critical questions were repeatedly met with resistance from the bank and its top management level, even when repeatedly asked by the regulator. This behaviour is difficult to understand,” Finma added.

The 2022 reports also show how Lex Greensill was able to “play off the different interests” within Credit Suisse “against each other”, according to Finma. A spokesperson for Lex Greensill did not immediately respond to a request seeking comment.

Since its state-sponsored takeover of Credit Suisse, UBS has been forced to handle the legacy issues of its former rival and has so far agreed to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to settle other legal cases. UBS says the Finma files deal with legacy Credit Suisse matters that predate the takeover.

Anonymous tips

The Finma files reveal that Credit Suisse’s management received several anonymous tips, warning them about Greensill Capital, on top of confronting a slew of “negative” articles from the FT and others about the group.

Greensill Capital claimed it used technology to revolutionise the staid niche of supply-chain finance, presenting its role as helping to address the problem of slow invoice payments.

In a December 2022 enforcement ruling, Finma said anonymous tips to the bank’s top management failed to prompt in-depth investigations.

“This is despite the fact that the specific content and wording of the anonymous references would suggest that they should be taken seriously,” Finma said. “The bank naively relied on information from Greensill.”

In one case, following an anonymous email that raised concerns about the bank’s relationship with Greensill, Michel Degen, who led the bank’s Swiss and Emea asset management unit, wrote to members of Credit Suisse’s executive board.

In the statement, Degen “described Greensill Capital as a successful and highly professional business partner that the bank had scrutinised in detail”, according to Finma. “He took the text used here verbatim from a statement by Lex Greensill,” the regulator added.

A lawyer representing Degen told the FT on Thursday that a statement from Greensill was added to the end of the email.

“If you are saying that Mr. Degen restated what Lex Greensill said, you are misreading the report,” Degen’s lawyer added.

Credit Suisse fired 11 employees who it deemed “jointly responsible” for the bank’s failing over Greensill, according to the files.

‘Negligent or worse’

The Finma reports shed more light on the fallout from an FT article that in 2020 revealed that Greensill’s backer SoftBank had invested in the Credit Suisse funds, which were also lending substantial amounts to other companies backed by the Japanese technology group.

The bank initially issued a statement claiming that the recent media reports contained “inaccurate and misleading statements”. However, after an internal investigation, Credit Suisse discovered that executives had signed a so-called “side letter” with SoftBank that breached the rules of the funds.

The chair of Credit Suisse’s audit committee stated in an email about the investigation’s findings: “The behaviour of the executives is, I am sorry to say that, either negligent or worse.”

Credit Suisse reprimanded two employees over the side letter, handing them a “final warning”. Details of this reprimand included in the Finma files show that a “misleading” statement had been communicated to the regulator about the funds.

Corporate spies sent in

The reports also show Credit Suisse executives tried unsuccessfully to push Greensill to reduce funding to Gupta’s GFG Alliance, exposure to which caused major losses for the bank’s clients after Greensill’s collapse.

According to Finma’s ruling, Credit Suisse hired a private investigations firm, Diligence, to produce a report on GFG in 2018, due to growing concerns about the liquidity of the group.

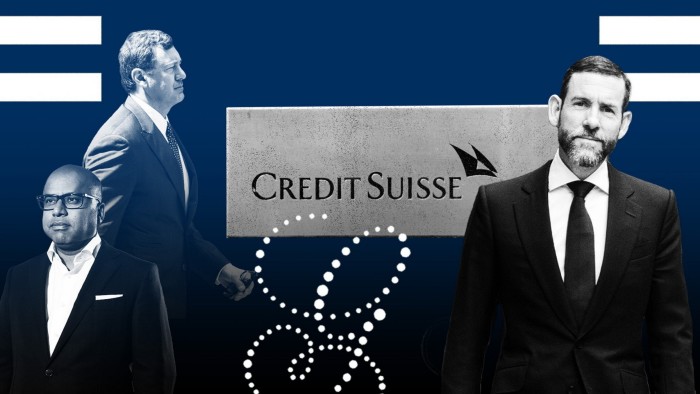

This was a year before a spying scandal hit the bank, which would eventually precipitate the exit of Credit Suisse’s chief executive, Tidjane Thiam. The bank had separately ordered private investigators at Investigo to spy on its head of wealth management, Iqbal Khan, after he resigned to move to UBS.

The investigators’ GFG report raised several red flags around Gupta’s businesses, including allegations around undisclosed related party transactions and their suspected participation in a “carousel fraud”, according to Finma’s ruling.

GFG later came under investigation from the UK’s Serious Fraud Office, but has denied wrongdoing. GFG declined to comment.

Plans to reduce the funds’ exposure to Gupta’s companies were discussed as early as December 2018, the same month the bank’s head of compliance shared the findings from the private investigators’ report with colleagues.

Lex Greensill made a series of pledges to reduce the Gupta exposure, telling Credit Suisse executives: “You have it in blood from me. No ifs and no buts. I am personally committing to these”. However, Finma found that the Australian also “put pressure on the portfolio management to buy bonds that actually increased the exposure”.

Employees frequently expressed alarm at the continued high exposure of the funds to Gupta’s businesses, with one senior executive emailing a colleague: “Why is GFG back at 1bn!!!!!”

‘I don’t know if I find that very reassuring’

The Finma files also shed light on the bank’s attempts to get to grips with Greensill’s practice of financing so-called “future receivables”, a term for hypothetical future invoices on trades that had yet to be agreed.

Finma found that Credit Suisse “was not in a position to distinguish between and monitor future and actual receivables”, while references to the term did not appear in the fund’s documents or marketing materials.

One employee who asked a senior colleague about the practice of financing future receivables was told in April 2020 that it was “all fine” as the issue had been discussed with Lex Greensill. The employee responded: “Hmmm. I don’t know if I find that very reassuring right now”.

Greensill collapsed less than a year later, in March 2021. Two years after that, Credit Suisse would follow it.

https://www.ft.com/content/19fb2879-e451-4b2f-b4f4-5173875f2854