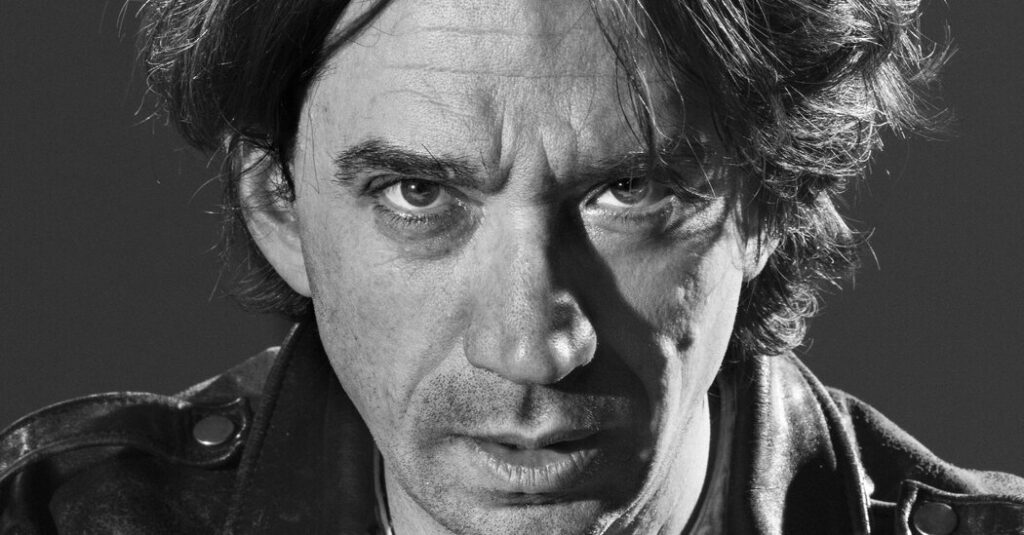

For a long time, Curtis Yarvin, a 51-year-old computer engineer, has written online about political theory in relative obscurity. His ideas were pretty extreme: that institutions at the heart of American intellectual life, like the mainstream media and academia, have been overrun by progressive groupthink and need to be dissolved. He believes that government bureaucracy should be radically gutted, and perhaps most provocative, he argues that American democracy should be replaced by what he calls a “monarchy” run by what he has called a “C.E.O.” — basically his friendlier term for a dictator. To support his arguments, Yarvin relies on what those sympathetic to his views might see as a helpful serving of historical references — and what others see as a highly distorting mix of gross oversimplification, cherry-picking and personal interpretation presented as fact.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Amazon | iHeart | NYT Audio App

But while Yarvin himself may still be obscure, his ideas are not. Vice President-elect JD Vance has alluded to Yarvin’s notions of forcibly ridding American institutions of so-called wokeism. The incoming State Department official Michael Anton has spoken with Yarvin about how an “American Caesar” might be installed into power. And Yarvin also has fans in the powerful, and increasingly political, ranks of Silicon Valley. Marc Andreessen, the venture capitalist turned informal adviser to President-elect Donald Trump, has approvingly cited Yarvin’s anti-democratic thinking. And Peter Thiel, a conservative megadonor who invested in a tech start-up of Yarvin’s, has called him a “powerful” historian. Perhaps unsurprising given all this, Yarvin has become a fixture of the right-wing media universe: He has been a guest on the shows of Tucker Carlson and Charlie Kirk, among others.

I’ve been aware of Yarvin, who mostly makes his living on Substack, for years and was mostly interested in his work as a prime example of growing antidemocratic sentiment in particular corners of the internet. Until recently, those ideas felt fringe. But given that they are now finding an audience with some of the most powerful people in the country, Yarvin can’t be so easily dismissed anymore.

One of your central arguments is that America needs to, as you’ve put it in the past, get over our dictator-phobia — that American democracy is a sham, beyond fixing, and having a monarch-style leader is the way to go. So why is democracy so bad, and why would having a dictator solve the problem? Let me answer that in a way that would be relatively accessible to readers of The New York Times. You’ve probably heard of a man named Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Yes. I do a speech sometimes where I’ll just read the last 10 paragraphs of F.D.R.’s first inaugural address, in which he essentially says, Hey, Congress, give me absolute power, or I’ll take it anyway. So did F.D.R. actually take that level of power? Yeah, he did. There’s a great piece that I’ve sent to some of the people that I know that are involved in the transition —

Who? Oh, there’s all sorts of people milling around.

Name one. Well, I sent the piece to Marc Andreessen. It’s an excerpt from the diary of Harold Ickes, who is F.D.R.’s secretary of the interior, describing a cabinet meeting in 1933. What happens in this cabinet meeting is that Frances Perkins, who’s the secretary of labor, is like, Here, I have a list of the projects that we’re going to do. F.D.R. personally takes this list, looks at the projects in New York and is like, This is crap. Then at the end of the thing, everybody agrees that the bill would be fixed and then passed through Congress. This is F.D.R. acting like a C.E.O. So, was F.D.R. a dictator? I don’t know. What I know is that Americans of all stripes basically revere F.D.R., and F.D.R. ran the New Deal like a start-up.

The point you’re trying to make is that we have had something like a dictator in the past, and therefore it’s not something to be afraid of now. Is that right? Yeah. To look at the objective reality of power in the U.S. since the Revolution. You’ll talk to people about the Articles of Confederation, and you’re just like, Name one thing that happened in America under the Articles of Confederation, and they can’t unless they’re a professional historian. Next you have the first constitutional period under George Washington. If you look at the administration of Washington, what is established looks a lot like a start-up. It looks so much like a start-up that this guy Alexander Hamilton, who was recognizably a start-up bro, is running the whole government — he is basically the Larry Page of this republic.

Curtis, I feel as if I’m asking you, What did you have for breakfast? And you’re saying, Well, you know, at the dawn of man, when cereals were first cultivated — I’m doing a Putin. I’ll speed this up.

Then answer the question. What’s so bad about democracy? To make a long story short, whether you want to call Washington, Lincoln and F.D.R. “dictators,” this opprobrious word, they were basically national C.E.O.s, and they were running the government like a company from the top down.

So why is democracy so bad? It’s not even that democracy is bad; it’s just that it’s very weak. And the fact that it’s very weak is easily seen by the fact that very unpopular policies like mass immigration persist despite strong majorities being against them. So the question of “Is democracy good or bad?” is, I think, a secondary question to “Is it what we actually have?” When you say to a New York Times reader, “Democracy is bad,” they’re a little bit shocked. But when you say to them, “Politics is bad” or even “Populism is bad,” they’re like, Of course, these are horrible things. So when you want to say democracy is not a good system of government, just bridge that immediately to saying populism is not a good system of government, and then you’ll be like, Yes, of course, actually policy and laws should be set by wise experts and people in the courts and lawyers and professors. Then you’ll realize that what you’re actually endorsing is aristocracy rather than democracy.

It’s probably overstated, the extent to which you and JD Vance are friends. It’s definitely overstated.

But he has mentioned you by name publicly and referred to “dewokeification” ideas that are very similar to yours. You’ve been on Michael Anton’s podcast, talking with him about how to install an American Caesar. Peter Thiel has said you’re an interesting thinker. So let’s say people in positions of power said to you: We’re going to do the Curtis Yarvin thing. What are the steps that they would take to change American democracy into something like a monarchy? My honest answer would have to be: It’s not exactly time for that yet. No one should be reading this panicking, thinking I’m about to be installed as America’s secret dictator. I don’t think I’m even going to the inauguration.

Were you invited? No. I’m an outsider, man. I’m an intellectual. The actual ways my ideas get into circulation is mostly through the staffers who swim in this very online soup. What’s happening now in D.C. is there’s definitely an attempt to revive the White House as an executive organization which governs the executive branch. And the difficulty with that is if you say to anyone who’s professionally involved in the business of Washington that Washington would work just fine or even better if there was no White House, they’ll basically be like, Yeah, of course. The executive branch works for Congress. So you have these poor voters out there who elected, as they think, a revolution. They elected Donald Trump, and maybe the world’s most capable C.E.O. is in there —

Your point is that the way the system’s set up, he can’t actually get that much done. He can block things, he can disrupt it, he can create chaos and turbulence, but he can’t really change what it is.

Do you think you’re maybe overstating the inefficacy of a president? You could point to the repeal of Roe as something that’s directly attributable to Donald Trump being president. One could argue that the Covid response was attributable to Donald Trump being president. Certainly many things about Covid were different because Donald Trump was president. I’ll tell you a funny story.

Sure. At the risk of bringing my children into the media: In 2016, my children were going to a chichi, progressive, Mandarin-immersion school in San Francisco.

Wait. You sent your kids to a chichi, progressive school? I’m laughing. Of course. Mandarin immersion.

When the rubber hits the road — You can’t isolate children from the world, right? At the time, my late wife and I adopted the simple expedient of not talking about politics in front of the children. But of course, everyone’s talking about it at school, and my son comes home, and he has this very concrete question. He’s like, Pop, when Donald Trump builds a wall around the country, how are we going to be able to go to the beach? I’m like: Wow, you really took him literally. Everybody else is taking him literally, but you really took him literally. I’m like, If you see anything in the real world around you over the next four years that changes as a result of this election, I’ll be surprised.

In one of your recent newsletters, you refer to JD Vance as a “normie.” What do you mean? [Laughs.] The thing that I admire about Vance and that’s really remarkable about him as a leader is that he contains within him all kinds of Americans. His ability to connect with flyover Americans in the world that he came from is great, but the other thing that’s neat about him is that he went to Yale Law School, and so he is a fluent speaker of the language of The New York Times, which you cannot say about Donald Trump. And one of the things that I believe really strongly that I haven’t touched on is that it’s utterly essential for anything like an American monarchy to be the president of all Americans. The new administration can do a much better job of reaching out to progressive Americans and not demonizing them and saying: “Hey, you want to make this country a better place? I feel like you’ve been misinformed in some ways. You’re not a bad person.” This is, like, 10 to 20 percent of Americans. This is a lot of people, the NPR class. They are not evil people. They’re human beings. We’re all human beings, and human beings can support bad regimes.

As you know, that’s a pretty different stance than the stance you often take in your writing, where you talk about things like dewokeification; how people who work at places like The New York Times should all lose our jobs; you have an idea for a program called RAGE: Retire All Government Employees; you have ideas that I hope are satirical about how to handle nonproductive members of society that involve basically locking them in a room forever. Has your thinking shifted? No, no, no. My thinking has definitely not shifted. You’re finding different emphases. When I talk about RAGE, for example: Both my parents worked for the federal government. They were career federal employees.

That’s a little on the nose from a Freudian perspective. It is. But when you look at the way to treat those institutions, treat it like a company that goes out of business, but sort of more so, because these people having had power have to actually be treated even more delicately and with even more respect. Winning means these are your people now. When you understand the perspective of the new regime with respect to the American aristocracy, their perspective can’t be this anti-aristocratic thing of, We’re going to bayonet all of the professors and throw them in ditches or whatever. Their perspective has to be that you were a normal person serving a regime that did this really weird and crazy stuff.

How invested do you think JD Vance is in democracy? It depends what you mean by democracy. The problem is when people equate democracy with good government. I would say that what JD Vance believes is that governments should serve the common good. I think that people like JD and people in the broader intellectual scene around him would all agree on that principle. Now, I don’t know what you mean by “democracy” in this context. What I do know is that if democracy is against the common good, it’s bad, and if it’s for the common good, it’s good.

There was reporting in 2017 by BuzzFeed — they published some emails between you and the right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, where you talked about watching the 2016 election with Peter Thiel and referred to him as “fully enlightened.” What would “fully enlightened” have meant in that context? Fully enlightened for me means fully disenchanted. When a person who lives within the progressive bubble of the current year looks at the right or even the new right, what’s hardest to see is that what’s really shared is not a positive belief but an absence of belief. We don’t worship these same gods. We do not see The New York Times and Harvard as divinely inspired in any sense, or we do not see their procedures as ones that always lead to truth and wisdom. We do not think the U.S. government works well.

And this absence of belief is what you call enlightened? Yes. It’s a disenchantment from believing in these old systems. And the thing that should replace that disenchantment is not, Oh, we need to do things Curtis’s way. It’s basically just a greater openness of mind and a greater ability to look around and say: We just assume that our political science is superior to Aristotle’s political science because our physics is superior to Aristotle’s physics. What if that isn’t so?

The thing that you have not quite isolated yet is why having a strongman would be better for people’s lives. Can you answer that? Yes. I think that having an effective government and an efficient government is better for people’s lives. When I ask people to answer that question, I ask them to look around the room and point out everything in the room that was made by a monarchy, because these things that we call companies are actually little monarchies. You’re looking around, and you see, for example, a laptop, and that laptop was made by Apple, which is a monarchy.

This is an example you use a lot, where you say, If Apple ran California, wouldn’t that be better? Whereas if your MacBook Pro was made by the California Department of Computing, you can only imagine it. I’m sorry, I’m here in this building, and I keep forgetting to make my best argument for monarchy, which is that people trust The New York Times more than any other source in the world, and how is The New York Times managed? It is a fifth-generation hereditary absolute monarchy. And this was very much the vision of the early progressives, by the way. The early progressives, you go back to a book like “Drift and Mastery” —

I have to say, I find the depth of your background information to be obfuscating, rather than illuminating. How can I change that?

By answering the questions more directly and succinctly. [Laughs.] Fine, I’ll try.

Your ideas are seemingly increasingly popular in Silicon Valley. Don’t you think there’s some level on which that world is responding because you’re just telling them what they want to hear? If more people like me were in charge, things would be better. I think that’s almost the opposite of the truth. There’s this world of real governance that someone like Elon Musk lives in every day at SpaceX, and applying that world, thinking, Oh, this is directly contradictory to the ideals that I was taught in this society, that’s a really difficult cognitive-dissonance problem, even if you’re Elon Musk.

It would be an understatement to say that humanity’s record with monarchs is mixed at best. The Roman Empire under Marcus Aurelius seems as if it went pretty well. Under Nero, not so much. Spain’s Charles III is a monarch you point to a lot; he’s your favorite monarch. But Louis XIV was starting wars as if they were going out of business. Those are all before the age of democracy. And then the monarchs in the age of democracy are just terrible.

Terrible! I can’t believe I’m saying this: If you put Hitler aside, and only look at Mao, Stalin, Pol Pot, Pinochet, Idi Amin — we’re looking at people responsible for the deaths of something like 75 to 100 million people. Given that historical precedent, do we really want to try a dictatorship? Your question is the most important question of all. Understanding why Hitler was so bad, why Stalin was so bad, is essential to the riddle of the 20th century. But I think it’s important to note that we don’t see for the rest of European and world history a Holocaust. You can pull the camera way back and basically say, Wow, since the establishment of European civilization, we didn’t have this kind of chaos and violence. And you can’t separate Hitler and Stalin from the global democratic revolution that they’re a part of.

I noticed when I was going through your stuff that you make these historical claims, like the one you just made about no genocide in Europe between 1,000 A.D. and the Holocaust, and then I poke around, and it’s like, Huh, is that true? My skepticism comes from what I feel is a pretty strong cherry-picking of historical incidents to support your arguments, and the incidents you’re pointing to are either not factually settled or there’s a different way of looking at them. But I want to ask a couple of questions about stuff that you’ve written about race. Mm.

I’ll read you some examples: “This is the trouble with white nationalism. It is strategically barren. It offers no effective political program.” To me, the trouble with white nationalism is that it’s racist, not that it’s strategically unsophisticated. Well —

There’s two more. “It is very difficult to argue that the Civil War made anyone’s life more pleasant, including that of freed slaves.” Come on. [Yarvin’s actual quote called it “the War of Secession,” not the Civil War.] The third one: “If you ask me to condemn Anders Breivik” — the Norwegian mass murderer — “but adore Nelson Mandela, perhaps you have a mother you’d like to [expletive].” When you look at Mandela, the reason I said that — most people don’t know this — there was a little contretemps when Mandela was released because he actually had to be taken off the terrorist list.

Maybe the more relevant point is that Nelson Mandela was in jail for opposing a viciously racist apartheid regime. The viciously racist apartheid regime, they had him on the terrorist list.

What does this have to do with equating Anders Breivik, who shot people on some bizarre, deluded mission to rid Norway of Islam, with Nelson Mandela? Because they’re both terrorists, and they both violated the rules of war in the same way, and they both basically killed innocent people. We valorize terrorism all the time.

So Gandhi is your model? Martin Luther King? Nonviolence? It’s more complicated than that.

Is it? I could say things about either, but let’s move on to one of your other examples. I think the best way to grapple with African Americans in the 1860s — just Google slave narratives. Go and read random slave narratives and get their experience of the time. There was a recent historian who published a thing — and I would dispute this, this number is too high — but his estimate was something like a quarter of all the freedmen basically died between 1865 and 1870.

I can’t speak to the veracity of that. But you’re saying there are historical examples in slave narratives where the freed slaves expressed regret at having been freed. This to me is another prime example of how you selectively read history, because other slave narratives talk about the horrible brutality. Absolutely.

“Difficult to argue that the Civil War made anyone’s life more pleasant, including freed slaves”? OK, first of all, when I said “anyone,” I was talking about a population group rather than individuals.

Are you seriously arguing that the era of slavery was somehow better than — If you look at the living conditions for an African American in the South, they are absolutely at their nadir between 1865 and 1875. They are very bad because basically this economic system has been disrupted.

I can’t believe I’m arguing this. Brazil abolished slavery in the 1880s without a civil war, so when you look at the cost of the war or the meaning of the war, it visited this huge amount of destruction on all sorts of people, Black and white. All of these evils and all of these goods existed in people at this time, and what I’m fighting against in both of those quotes, also in the way the people respond to Breivik — basically you’re responding in this cartoonish way. What is the difference between a terrorist and a freedom fighter? That’s a really important question in 20th-century history. To say that I’m going to have a strong opinion about this stuff without having an answer to that question, I think is really difficult and wrong.

You often draw on the history of the predemocratic era, and the status of women in that time period, which you valorize, is not something I’ve seen come up in your writing. Do you feel as if your arguments take enough into account the way that monarchies and dictatorships historically have not been great for swaths of demographics? When I look at the status of women in, say, a Jane Austen novel, which is well before Enfranchisement, it actually seems kind of OK.

Women who are desperate to land a husband because they have no access to income without that? Have you ever seen anything like that in the 21st century? I mean the whole class in Jane Austen’s world is the class of U.B.I.-earning aristocrats, right?

You’re not willing to say that there were aspects of political life in the era of kings that were inferior or provided less liberty for people than political life does today? You did a thing that people often do where they confuse freedom with power. Free speech is a freedom. The right to vote is a form of power. So the assumption that you’re making is that through getting the vote in the early 20th century in England and America, women made life better for themselves.

Do you think it’s better that women got the vote? I don’t believe in voting at all.

Do you vote? No. Voting basically enables you to feel like you have a certain status. “What does this power mean to you?” is really the most important question. I think that what it means to most people today is that it makes them feel relevant. It makes them feel like they matter. There’s something deeply illusory about that sense of mattering that goes up against the important question of: We need a government that is actually good and that actually works, and we don’t have one.

The solution that you propose has to do with, as we’ve said multiple times, installing a monarch, a C.E.O. figure. Why do you have such faith in the ability of C.E.O.s? Most start-ups fail. We can all point to C.E.O.s who have been ineffective. And putting that aside, a C.E.O., or “dictator,” is more likely to think of citizens as pure economic units, rather than living, breathing human beings who want to flourish in their lives. So why are you so confident that a C.E.O. would be the kind of leader who could bring about better lives for people? It seems like such a simplistic way of thinking. It’s not a simplistic way of thinking, and having worked inside the salt mines where C.E.O.s do their C.E.O.ing, and having been a C.E.O. myself, I think I have a better sense of it than most people. If you took any of the Fortune 500 C.E.O.s, just pick one at random and put him or her in charge of Washington. I think you’d get something much, much better than what’s there. It doesn’t have to be Elon Musk.

Earlier you had said that regardless of what his goals are, Trump isn’t likely to get anything transformative accomplished. But what is your opinion of Trump generally? I talked about F.D.R. earlier, and a lot of people in different directions might not appreciate this comparison, but I think Trump is very reminiscent of F.D.R. What F.D.R. had was this tremendous charisma and self-confidence combined with a tremendous ability to be the center of the room, be the leader, cut through the BS and make things happen. One of the main differences between Trump and F.D.R. that has held Trump back is that F.D.R. is from one of America’s first families. He’s a hereditary aristocrat. The fact that Trump is not really from America’s social upper class has hurt him a lot in terms of his confidence. That’s limited him as a leader in various ways. One of the encouraging things that I do see is him executing with somewhat more confidence this time around. It’s almost like he actually feels like he knows what he’s doing. That’s very helpful, because insecurity and fragility, it’s his Achilles’ heel.

What’s your Achilles’ heel? I also have self-confidence issues. I won’t bet fully on my own convictions.

Are there ways in which your insecurity manifests itself in your political thinking? That’s a good question. If you look at especially my older work, I had this kind of joint consciousness that, OK, I feel like I’m onto something here, but also — the idea that people would be in 2025 taking this stuff as seriously as they are now when I was writing in 2007, 2008? I mean, I was completely serious. I am completely serious. But when you hit me with the most outrageous quotes that you could find from my writing in 2008, the sentiments behind that were serious sentiments, and they’re serious now. Would I have expressed it that way? Would I have trolled? I’m always trying to get less trollish. On the other hand, I can’t really resist trolling Elon Musk, which might be part of the reason why I’ve never met Elon Musk.

Do you think your trolling instinct has gotten out of hand? No, it hasn’t gone far enough. [Laughs.] What I realize when I look back is that the instinct to revise things from the bottom up is very much not a trollish instinct. It’s a serious and an important thing that I think the world needs.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations. Listen to and follow “The Interview” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, iHeartRadio, Amazon Music or the New York Times Audio app.

Director of photography (video): Tre Cassetta

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/18/magazine/curtis-yarvin-interview.html