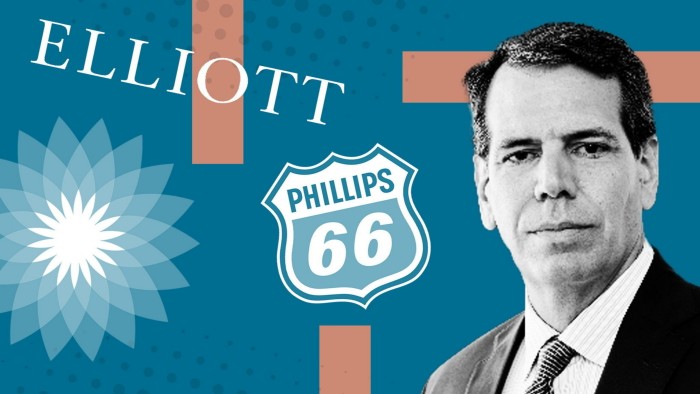

John Pike had his target in his sights. The Elliott Management partner was facing off against the chief executive of Phillips 66, the oil and gas giant in which he had built a $2.5bn stake, across a Manhattan meeting room.

Over the course of an hour, the Texan company and its legion of defence advisers had a final chance to negotiate a truce with the world’s most feared activist hedge fund and avert the type of expensive proxy fight for which Pike was becoming known. They failed.

Within 24 hours Elliott had launched one of the most aggressive activist campaigns the energy sector had seen in years with a full-blown proxy battle for four seats on Phillips 66’s board, nominating a slate of new directors.

The fight underlines how even as rivals have switched to behind-the-scenes lobbying and Elliott itself has softened its style, Pike embodies the hedge fund’s “old aggressive style”, according to former colleagues.

The firm’s campaigns had become increasingly “corporatised and mature”, said another person who has come up against Elliott several times. But even though it emphasised its collegial nature, Pike’s approach stood out, they said, calling him “a lone wolf inside of Elliott who wants to do things a different way”.

Under Pike, Elliott has taken a series of high-profile energy positions in recent months, seeking to guide the direction of blue-chip companies from BP in the UK to RWE in Germany — as well as at Phillips 66 in the US.

“If you look at the most interesting campaigns Elliott is running right now, they are all his,” said another person who has dealt with Pike in a number of situations.

To those who have worked with him, Pike is considered one of Elliott’s shrewdest investors.

A 22-year Elliott veteran, Pike oversees “global situational teams” with specific expertise in energy — as well as utilities, transportation, mining and insurance — and became an equity partner in 2022. Last year, he ascended to its powerful 12-person management committee.

A college basketball player who grew up in southern California and later graduated from Yale Law School, Pike’s demeanour is calm and deliberate. He keeps a low profile: the only image of him online is from his nomination to the Phillips 66 board.

“It’s not hard to change John’s mind, you just have to be right,” said Quentin Koffey, who worked with Pike for seven years before leaving Elliott and later setting up his own activist fund, Politan Capital Management. “He responds to well-reasoned analysis, and is neither provoked nor swayed by shallow campaign rhetoric or ad hominem attacks.”

His investment record points to a more ruthless style.

Since Pike first picked a fight with US oil and gas group Hess in 2013, Elliott has invested at least $21.6bn in publicly traded energy companies, according to analysis by the Financial Times and data provider Def 14 Inc.

Three of the four campaigns targeting major US corporations in which Elliott has gone so far as to mail proxy materials to shareholders have been led by Pike. Since his battle with Hess, Pike has won 13 board seats across five companies in the energy sector alone.

Elliott’s energy campaigns are linked by a common thread: the break-up of large energy conglomerates to refocus them on their core competencies. It routinely calls for asset divestments, as it did at Hess, Suncor Energy and Marathon Petroleum.

But another link is the firm’s opposition to traditional energy companies owning renewable businesses.

Elliott has run one campaign where it supported greater renewables deployment, at a company called Evergy in 2020. The trend has been in the other direction, however.

At NRG Energy and BP, the activist has pushed for the offloading of renewable businesses — moves that align with the political leanings of Elliott’s founder, Paul Singer, according to people who know him. Others insist the campaigns have nothing to do with personal politics.

One former Elliott employee said: “They believe the energy transition . . . is expensive and time-consuming.” A recent letter to investors said the “net zero” agenda imposed “massive costs” and acted as a “drag on growth”.

Until recently, this view went against the prevailing wind, where big fund managers encouraged oil majors to push further into renewables and reduce carbon emissions.

But since Elliott’s large stake in BP became public in February, the UK oil major has already changed course. Its chair Helge Lund has announced plans to step down, the company has pledged to speed up its pivot away from renewables, and it has fast-tracked $20bn of asset divestments. It has also promised to increase investment in oil and gas by 25 per cent.

Elliott wants more. Earlier this week, the hedge fund upped its stake past 5 per cent, and has told the UK energy company that it wants it to boost free cash flow to $20bn by 2027 by more aggressively controlling costs and capital expenditure, according to people familiar with discussions.

Changing the course of the roughly £57bn oil major will be no mean feat.

“In Europe, board changes are much more difficult,” said Christopher Kuplent, an analyst at Bank of America. “And if you look at the campaigns where [Elliott] have not been able to effect board changes, they have failed.”

“BP is the lowest-quality supermajor oil company . . . there is no quick fix,” said Per Lekander, managing partner at hedge fund Clean Energy Transition.

Back at Phillips 66, Elliott’s 17-month campaign is reaching a denouement.

Unless one side blinks, shareholders will next month choose between the four directors proposed by Elliott and the ones put up by Phillips 66 in a full-blown proxy vote: a Rubicon that Elliott has never crossed against a major US corporation. Phillips 66 this week raised the stakes with a letter to shareholders accusing Elliott of being conflicted due to its pursuit of a rival, Citgo.

Success for Elliott increases the likelihood of asset sales, including the company’s midstream business and its chemicals joint venture with Chevron, as well as a shake-up of the management team.

Phillips 66 has been Pike’s most combustible campaign since he took on Hess, his maiden campaign in the energy sector that settled just hours before a shareholder vote.

Although Elliott went quiet on Hess after just a year, the investor held on to its position there for the best part of a decade before finally cashing out.

Taking the fight to Phillips 66 and BP may require the same patience.

Rich Kruger, who was installed as Suncor Energy’s chief executive in 2023, a year after Elliott took a stake, said the activist sometimes gave voice to what other investors were thinking.

Suncor’s shares gained as much as 41 per cent from when the activist first unveiled its demands in April 2022 and their high in November last year.

“I’ve had a lot of hallelujahs from my long-term shareholders about Elliott’s strategy,” he said. “Maybe they’re a little bit more patient and less aggressive than Elliott, but I think they look for the same outcomes.”

Additional reporting by Tom Wilson. Data visualisation by Louis Ashworth.

https://www.ft.com/content/4d74c192-790b-4413-a34a-c9bc866d2075