Rutherford Chang, a conceptual artist who turned his collection of the Beatles’ “White Album” into a meditation on the aging of a vinyl classic — and who, in another project, melted down 10,000 pennies into a copper block to make a statement about the value of each red cent — died on Jan. 24 at his home in Manhattan. He was 45.

His sister Danielle Chang said that a specific cause would not be determined for several months.

Mr. Chang’s projects were the fruit of a playful, obsessive mind. In “Andy Forever” he and a colleague edited all of the Hong Kong movie star Andy Lau’s death scenes, in chronological order of the films’ release, into a 27-minute video.

In another video, “Dead Air,” he removed all the words from President George W. Bush’s 2003 State of the Union speech (including those about the Iraqi despot Saddam Hussein’s ambitions to build nuclear and biological weapons), leaving only his pauses, his breaths and the applause from the House chamber.

And he cut and pasted a 2004 front page of The New York Times, rearranging all the text into alphabetical order. Some of it, when read aloud, sounds like Yoda, the “Star Wars” character who spoke in an idiosyncratic style. One headline read, “a Abuse Aide And Clash General on Rumsfeld.”

“He was obsessive, but not compulsive,” Ms. Chang, his sister, said. “He was a collector. His apartment is so orderly, with nothing out of place, but he threw nothing away.”

Mr. Chang was not initially a collector of the 1968 double LP “The Beatles,” better known as “The White Album.” He bought one copy of it as a teenager, but when he got a second one some years later, he realized that the two — with their plain white covers as blank canvases— had changed over time.

“The more I got, the more I could see how different these once identical objects had become,” he told the website The Creative Independent in 2017. “I didn’t know where it was going when I started other than that I wanted at least enough to see the differences between them. Then it just kept going and I can’t stop.”

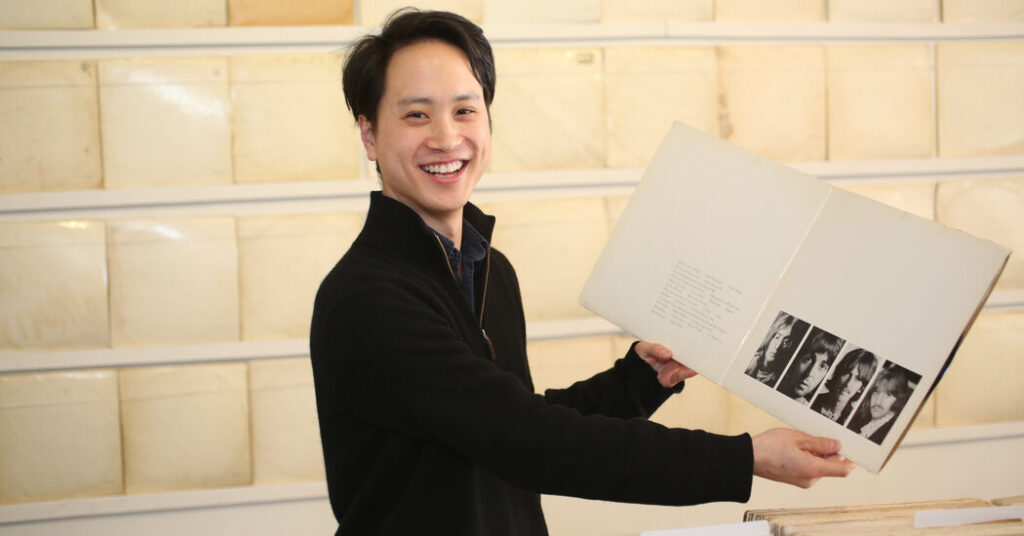

Mr. Chang’s installation, “We Buy White Albums,” unveiled at the Recess gallery in Manhattan in 2013, took the form of a facsimile of a record shop, with albums in bins and turntables to play the music.

One wall was filled with albums whose owners had put their names on the covers, as well as written letters, poems and other ephemera on them. Some had drawn pictures. The covers also showed wear patterns created by rotting cardboard.

“Each album has aged uniquely and become an artifact of the last half-century,” Mr. Chang told the website Hyperallergic in 2013.

The exhibition — which traveled to several cities, including Liverpool, the home of the Beatles, in 2014 — also had an audio component.

When he listened to copies of “The White Album” at the gallery, Mr. Chang used a professional recording device connected to the turntables to make a digital recording; he later had a studio electronically layer 100 of them into a pressing of 1,000 vinyl records, with all the static, scratches and skips of the original recordings. He sold some copies for $20 each and traded others for more “White Albums” (his collection reached 3,417 copies). He also posted some of the audio on his website.

His vinyl record offered a unique spin on “The White Album.” Variations in the factory pressings and fluctuations in the speed of Mr. Chang’s turntable caused oddities, Allan Kozinn wrote in The Times in 2013: “At the start of ‘Dear Prudence,’ you hear the first line echoing several times, and by ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ the track is a nearly unrecognizable roar.”

Rutherford Chang was born on Dec. 27, 1979, in Houston to parents from Taiwan and grew up in Los Altos Hills, Calif., near Palo Alto. His father, Jason, is a founder of ASE Technology Holding, a semiconductor company, and his mother, Ching Ping (Hsiang) Chang, is a retired interior designer who manages the home.

Rutherford’s earliest collection, when he was a child, was of the small stickers that come with fruit, which he used to decorate a binder. Throughout his life, he would collect many other things: baseball bats, hotel stationery, postcards, old Chinese megaphones, years’ worth of receipts.

“He had a unique way of looking at the world,” Ms. Chang said. “He saw beauty in everyday objects.”

After majoring in psychology while taking art courses at Wesleyan University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 2002, he was an assistant to the artist Xu Bing in Manhattan for two years. He then worked on his own projects in Singapore and Beijing.

In 2008, he clipped about 4,000 ink-dot portraits from The Wall Street Journal, then reassembled them in alphabetical order into a yearbook-like publication he called “The Class of 2008.” He repeated several portraits; Barack Obama, who was elected president of the United States that year, appears 94 times, and John McCain, his Republican opponent, appears 74 times.

When it was exhibited at the White Space Gallery in Beijing in 2012, The Journal called Mr. Chang’s project an “illuminating window into the priorities and thought processes of The Journal as it sought to document the year’s events.”

Mr. Chang turned his fascination with video games into performance art: In 2016, he livestreamed on the platform Twitch his attempt to achieve the world’s highest score in Game Boy Tetris, the 1990s puzzle game.

By then, he had been playing Tetris since childhood (his goal was to beat the score of Steve Wozniak, a founder of Apple) and recorded more than 1,700 videos of his game playing. The videos were exhibited at the Container, a gallery in Tokyo, also in 2016.

Mr. Chang told The Guardian that year that playing Tetris serially mimicked the drudgery of the modern office, where “we’re expected to repeat a specific task over and over.” He added, “It’s the way capitalism makes us work, where you have to achieve more than others.”

His high score of 614,094 earned him second place in world rankings for a while.

Mr. Chang’s last major project, “Cents,” examined the nature of value and was anchored in both the analog and digital worlds. Around 2017, he began to casually set aside pennies from the change he received, he told The Creative Independent, with no particular goal.

He knew, he said, that some hoarders were exchanging cash for rolls of pennies at banks and then sorting out the more valuable ones from the ones made before 1982, when they were 95 percent copper and 5 percent zinc, making each one worth up to 3.1 cents. But, he said, a hoarder couldn’t achieve much value without large quantities of the older copper.

“I’ve been thinking about what I could do with melting them down,” he said, “even though it’s illegal” because pennies are currency. “The penny is this thing that we all have in our pockets. It’s the lowest common denominator, it’s like junk, it’s like nothing.”

He ultimately figured out what he would do. He collected 10,000 pennies from 1982 and earlier; documented and inscribed them on the blockchain, a digital database, and melted them down into a 68-pound cube.

A three-dimensional model of the cube was auctioned by Christie’s last year as a bitcoin ordinal, a digital asset, for $50,400 — Mr. Chang retained the physical cube — while the digital inscriptions on the pennies are owned by thousands of individuals and are sold on the open market.

In addition to his sister Danielle and his parents, Mr. Chang is survived by another sister, Madeline Chang, and his partner, Tsubasa Narita.

Aki Sasamoto, an artist and a professor at the Yale School of Art, had watched Mr. Chang build his body of work since they were housemates at Wesleyan. She said that he brought personality to conceptual art, a field often devoid of one, and that he was a sharp observer of cultural phenomena and new media.

While his work might look obsessive, Ms. Sasamoto said, “I find it is more like a thoroughness, in line with personal ritual and devotion. I relate it to someone who meditates every day. There was something spiritual about him.”