Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Two years ago today, Joe Biden was denouncing then-UK PM Liz Truss while in an ice cream parlour, calling her stricken economic plans a “mistake”.

Much energy has been expended since in re-litigating the gilt crisis that began in the wake of Truss and Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s now-infamous “mini-Budget”.

One of the key questions is this: how much of the yield spike was because of borrowing; how much was a “Moron Risk Premium”; how much was down to forced selling by leveraged pension funds running Liability Driven Investment schemes; and how much was it bond markets just kinda doing their thing?

Earlier this year, the Bank of England partially estimated this breakdown, using something called Liquidity After Solvency Hedging (or, LASH) risk. Toby analysed its findings and the response to them here, writing:

The scores on the doors over the 16-day ‘crisis period’, based on their analysis:

— Bond yield spike due to “bond vigilantes”, AKA the gilt market doing gilt market stuff = 37 bps

— Bond yield spike attributed to pension funds getting margin called because of market losses from the bond spike due to Truss/Kwarteng unfunded tax cuts, AKA doom looping = 66 bps

Zero years ago today, another analysis has dropped — this time authored by Sushil Wadhwani, writing for the Centre for Economic Policy Research’s Vox platform.

Wadhwani was chief investment officer of PGIM Wadhwani, the asset manager he founded, until the end of last year, and served on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee between 1999 and 2002 (he is the second-most-dovish member on record, with a net balance of 13 votes to cut rates according to FTAV analysis). He’s also a minor dramatis persona in the gilt crisis: brought in as part of former Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s advisory council in a bid to restore credibility in the wake of the crisis.

His views carry weight — so what does he reckon?

In today’s piece, “The role of borrowing in the rise of gilt yields during the Truss episode and some possible implications”, Wadhwani writes (our emphasis):

In this column, I consider a variety of different reasons for why UK yields might have risen during the ‘Truss period’ and show that the popular view might overstate the impact of higher borrowing. The analysis suggests that the projected increase in borrowing plausibly accounted for less than one-quarter of the observed rise in gilt yields during this period. I also discuss some implications of these findings for the plausible market impact of the UK government modifying its fiscal rules as a part of its forthcoming Budget on 30 October.

It’s a big claim, one Truss’s remaining media allies (and she herself) may look upon as evidence that she was unfairly punished for the gilt market meltdown.

It’s also potentially useful for now-Chancellor Rachel Reeves as she staves off concerns that a borrowing spree at the upcoming Budget could cause a new gilt crisis.

So what’s Wadhwani’s approach?

Looking at a trough-to-peak rise in yields of 288 basis points from early August 2022 to the height of the sell-off, he writes:

1. The actual rise in yields was 288 basis points

2. The implied rise in ‘excess yields’ was around 136 basis points, as perhaps 152 basis points of the rise can be accounted for by the rise in global yields.

3. The impact of the attack on macro institutions. I argued above that the impact of undermining the institutions was plausibly greater than that of higher borrowing. I therefore make the working assumption that the two factors contributed equally, which then suggests that the resulting estimate of the impact of higher borrowing falls to 68 basis points.

4. The impact of forced deleveraging. It is difficult to estimate the impact of the forced LDI selling, but is likely to have been non-trivial.

5. A plausible upper bound of the impact of higher borrowing on gilt yields. Steps 1-4 lead me to conclude that a plausible upper bound estimate of the contribution of higher government borrowing to ten-year gilt yields during the Truss episode is 68 basis points. It is notable that this number is even smaller than the lower end of Treasury estimates, which would have suggested a number of around 100 basis points. Note that reasonable people might disagree with how I dealt with factors (ii) and (iii) above, but I feel that the highly conservative assumption of no effect from deleveraging gives plenty of wiggle room.

Based on this, he concludes:

Therefore, far from the Truss episode suggesting that we should become more concerned about the impact of borrowing on interest rates than had been true historically, I believe that allowing for other relevant factors suggests that the actual borrowing-related impact on interest rates might have been even smaller than the lower end of the Treasury’s range of estimates…

I believe that the current Chancellor is in an entirely different place from the backdrop to the September 2022 budget

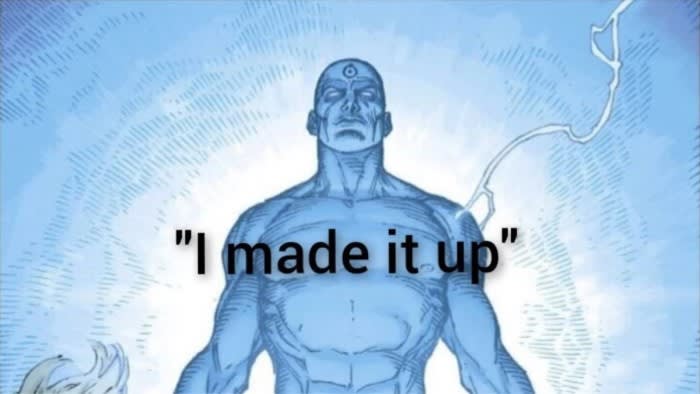

Regrettably, this approach is silly. Let’s look at this step by step:

1. The actual rise in yields was 288 basis points

2. The implied rise in ‘excess yields’ was around 136 basis points, as perhaps 152 basis points of the rise can be accounted for by the rise in global yields.

“Perhaps”. This portion is based on a “Truss period” window chosen by Wadhwani that dilutes the crisis spike by including the run-up, which he defines as:

the low/high relative to the period between the resignation of Prime Minister Johnson on 7 July and Prime Minister Truss’ departure on 20 October.

Wadhwani writes:

With international yields rising by about 150 basis points over this period, it would appear that the UK-specific component of the actual rise in UK gilt yields is only around one-half of it.

Now, we’re aware that some people consider the spike to mainly be a continuation of the run-up, but that’s probably a separate debate. Even if we accept the the premise that gilts would have moved totally in-line with USTs and bunds, the problem with the framing here is that by making the rise a function of temporal post-Johnsonism, the scale of the move during the crisis period is diluted. Was Truss inevitable? It’s one of several questions this approach avoids.

3. The impact of the attack on macro institutions. I argued above that the impact of undermining the institutions was plausibly greater than that of higher borrowing. I therefore make the working assumption that the two factors contributed equally, which then suggests that the resulting estimate of the impact of higher borrowing falls to 68 basis points.

Sorry, but this is pure guesswork. Looking at sterling’s parallel moves as a proxy, Wadhwani writes:

…it is plausible that the markets were worried about the undermining of the independent institutions relevant to the UK macroeconomic framework, or else the higher borrowing may have led to an exchange rate appreciation.

That’s obviously valid! Does that mean “that the two factors [higher borrowing and the institutional attack] contributed equally” is a reasonable assumption? Absolutely not!

4. The impact of forced deleveraging. It is difficult to estimate the impact of the forced LDI selling, but is likely to have been non-trivial.

It is difficult to estimate the impact chocolate has had on the author’s personal wealth, but it is likely to be non-trivial. So that’s sorted then.

5. A plausible upper bound of the impact of higher borrowing on gilt yields. Steps 1-4 lead me to conclude that a plausible upper bound estimate of the contribution of higher government borrowing to ten-year gilt yields during the Truss episode is 68 basis points. It is notable that this number is even smaller than the lower end of Treasury estimates, which would have suggested a number of around 100 basis points. Note that reasonable people might disagree with how I dealt with factors (ii) and (iii) above, but I feel that the highly conservative assumption of no effect from deleveraging gives plenty of wiggle room.

So:

— we set a time period from August 2nd, with a yield move of 288 bps

— we discount all of the pre-“mini-Budget” move because comparable global yields also went up. 288 – 152 = 136 bps.

— we simply cut that number in half based on a hunch. 136 / 2 = 68 bps.

— call that an upper bound because of a “non-trivial” amount of LDI selling. = <68 bps

Wadhwani says:

Note that reasonable people might disagree with how I dealt with factors (ii) and (iii) above, but I feel that the highly conservative assumption of no effect from deleveraging gives plenty of wiggle room.

We… probably qualify as reasonable people? And even if this analysis is right — and even if you want it to be right — it isn’t reasonable. It’s just vibes.

Further reading:

— Liz and the LASH

https://www.ft.com/content/96469060-9ee1-4205-922a-6f720fb14c1e