Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is a professor of entrepreneurship and associate dean of innovation at the MIT School of Management

On both sides of the Atlantic, governments are considering increasing taxes, especially those faced by investors. Among the proposals are increases to capital gains tax — the taxes that accrue on increases in the value of investments when they are realised. Added to that are proposed changes in the tax treatment of carried interest — rewards to investors who successfully invest funds entrusted to them by large institutions.

Not surprisingly, these suggestions have caused concern in the venture capital community. Moreover, evidence suggests that taxing the investors and entrepreneurs who are funding the next generation of start-ups is a counterintuitive move by policymakers who are also seeking to drive innovation and economic growth. Based on US evidence, when capital gains goes up, investment in start-ups declines.

That said, political reality suggests that capital gains increases are almost inevitable. So a different question is how this moment might be used to drive venture capital towards outcomes that matter most for our societies. What if we maintain lower rates for investment activities that drive innovation?

By focusing on the underlying behaviours we want to incentivise, we can structure taxes more effectively. When we provide tax breaks to companies for spending on R&D, we do it to spur behaviour we know is good for the overall health of the economy. For example, tax relief for energy storage batteries is an attempt to incentivise not just the rate of innovation but its direction. Why not capital gains too?

One of the criticisms of venture capital investing is that it focuses too much on supporting the sort of “quick win” ventures that use software to solve business or consumer needs. A handful of these extraordinary companies have provided exponential returns for their founders and investors. Naturally, investors have been laser-focused on the software sector to generate rapid returns.

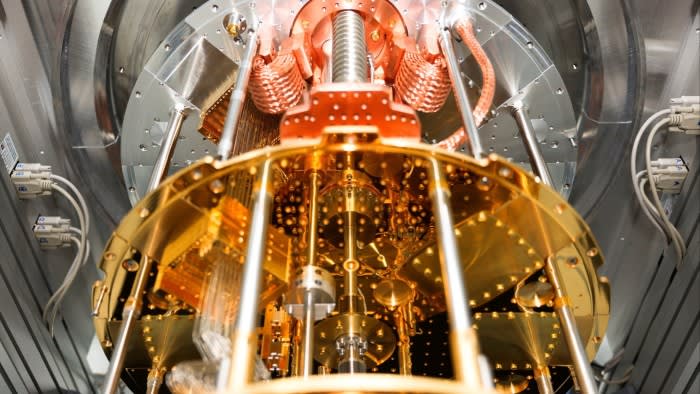

In response, governments have encouraged the venture community (and their pension fund backers) to increase investment in deep tech companies; from those designing next generation quantum computers to teams building novel space launch capabilities. Such ventures are capital intensive and importantly, take more time. Tax changes could be used to tip the scales.

For example, capital gains on investments in companies that are built on intellectual property from universities or national labs could be lower than the standard rate. And those who hold investments for a long period or invest in funds with longer time horizons could be rewarded.

Of course, the details matter and there are opportunities for gaming the system, but simply increasing all capital gains tax is too blunt an approach when some surgical reductions might have a positive impact.

This idea is not new: governments have a track record of changing investment tax rules to promote behaviours they value for our economy and society. The UK’s Enterprise Investment Scheme was created in 1994 to encourage private investment in young businesses by exempting capital gains tax. A later Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme was launched in 2012 to boost increase investment in start-ups to shift capital towards more innovation-driven ventures in hopes of encouraging the next Arm or Deepmind. The schemes have been demonstrably effective with more than 4,400 firms using EIS and 2300 start-ups using SEIS in the most recently reported tax year. Today, it could be targeted or expanded towards ventures that support other government priorities from health and clean energy to defence and security.

We might also take inspiration from the other side of the Atlantic where the 2017 Jobs Act was used to spur investment in specific locations referred to as opportunity zones. Capital gains was deferred from investments in new businesses (or funds) in these zones and were tax free if held for more than a decade.

A similar approach in the UK’s Investment Zones could provide an added boost for investments in R&D-focused businesses essential to these regional innovation ecosystems. Without making the tax code impossibly complex, now is a time for fresh thinking.

Leaders have an opportunity to carefully consider the investment attributes valued by our nations and use these as a road map to shape aspects of capital gains tax in ways that drive the key innovations that matter to our future.

https://www.ft.com/content/64ee43de-efbf-42dc-854f-8a5271995e1c