As a boy, Blas Omar Jaime spent many afternoons studying about his ancestors. Over yerba mate and torta fritas, his mom, Ederlinda Miguelina Yelón, handed alongside the information she had saved in Chaná, a throaty language spoken by barely transferring the lips or tongue.

The Chaná are an Indigenous individuals in Argentina and Uruguay whose lives had been intertwined with the mighty Paraná River, the second longest in South America. They revered silence, thought-about birds their guardians and sang their infants lullabies: Utalá tapey-’é, uá utalá dioi — sleep toddler, the solar has gone to sleep.

Ms. Miguelina Yelón urged her son to guard their tales by holding them secret. So it was not till a long time later, just lately retired and in search of out individuals with whom he may chat, that he made a startling discovery: No one else appeared to talk Chaná. Scholars had lengthy thought-about the language extinct.

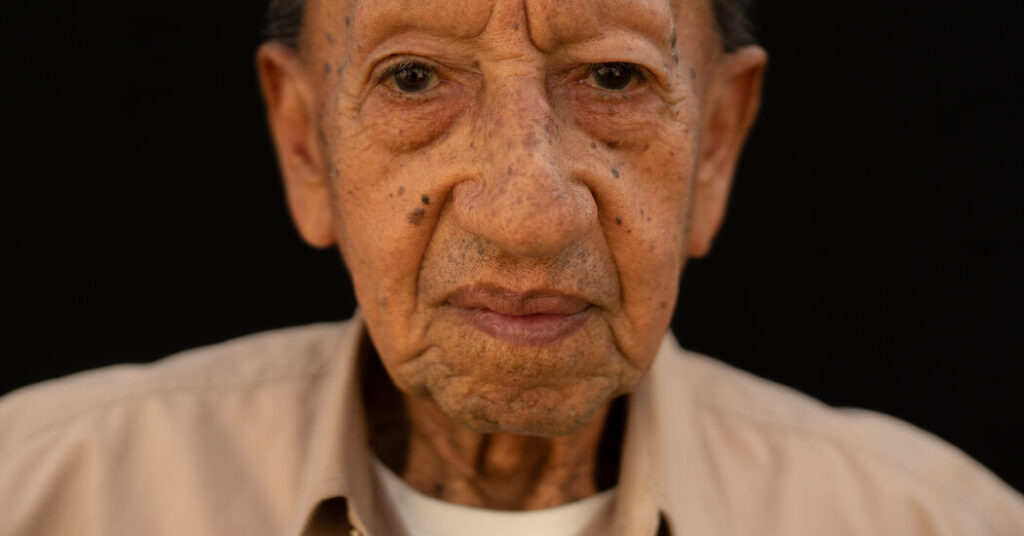

“I said: ‘I exist. I am here,’” mentioned Mr. Jaime, now 89, sitting in his sparse kitchen on the outskirts of Paraná, a midsize metropolis within the Argentine province of Entre Ríos.

Those phrases kicked off a journey for Mr. Jaime, who has spent almost 20 years resurrecting Chaná and, in some ways, inserting the Indigenous group again on the map. For UNESCO, whose mission contains the preservation of languages, he is a vital vault of data.

His painstaking work with a linguist has produced a dictionary of roughly 1,000 Chaná phrases. For individuals of Indigenous ancestry in Argentina, he’s a beacon that has impressed many to attach with their historical past. And for Argentina, he’s a part of an necessary, if nonetheless fraught, reckoning over its historical past of colonization and Indigenous erasure.

“Language is what gives you identity,” Mr. Jaime mentioned. “If someone doesn’t have their language, they’re not a people.”

Along the best way, Mr. Jaime has had brushes of superstar. The topic of a number of documentaries, he has delivered a TED Talk, lent his face and voice to a espresso model and has appeared in an academic cartoon in regards to the Chaná. Last yr, a recording of him talking Chaná echoed throughout downtown Buenos Aires as a part of an artist mission that sought to honor Argentina’s Indigenous historical past.

Now, a passing of the guard is underway, to his daughter Evangelina Jaime, who has discovered Chaná from her father and is educating it to others. (How many Chaná stay in Argentina is unclear.)

“It’s generations and generations of silence,” mentioned Ms. Jaime, 46. “But we won’t be silent anymore.”

Archaeologists hint the presence of Chaná individuals again roughly 2,000 years in what’s now the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe and Entre Rios, in addition to elements of present-day Uruguay. The first European report of the Chaná was made within the sixteenth century by Spanish explorers.

They fished, lived a nomadic life and had been expert clay artisans. With colonization, the Chaná had been displaced, their territory shrunk and their numbers dwindled as they assimilated into newly established Argentina, which launched navy campaigns to eradicate Indigenous communities and open land for settlement.

Before Mr. Jaime revealed his information of Chaná, the final recognized report of the language was in 1815, when Dámaso A. Larrañaga, a priest, met three older Chaná males in Uruguay and documented what he discovered in regards to the language in two notebooks. Only a type of books survived, containing 70 phrases.

The trove of knowledge that Mr. Jaime obtained from his mom was much more expansive. Ms. Miguelina Yelón was an adá oyendén — a “woman memory keeper” — somebody who historically preserved the group’s information.

According to Mr. Jaime, solely girls had been Chaná reminiscence keepers.

“This was a matriarchy,” mentioned Ms. Jaime. “Women were the ones who guided the Chaná people. But something happened — we’re not sure what — that made men take control again. And women agreed to cede that power in exchange for them being the only guardians of that history.”

Ms. Miguelina Yelón didn’t have any daughters to whom she may go alongside her information. (Her three daughters all died as youngsters.) So she turned to Mr. Jaime.

That is how he got here to spend his afternoons absorbing tales of the Chaná, studying phrases that described their world: “atamá” means “river”; “vanatí beáda” is “tree”; “tijuinem” means “god”; “yogüin” is “fire.”

His mom warned him to not share what he knew with anybody. “From the time we were born, we hid our culture, because in those days, you were discriminated against for being aboriginal,” he mentioned.

Decades handed. Mr. Jaime led a different life, working as a supply boy, in a publishing home, as a touring jewellery salesman, in a authorities transportation division, as a cabdriver and as a Mormon preacher. When he was 71 and retired, he was invited to an Indigenous occasion, and was nudged out into the gang to inform his story.

Since then, Mr. Jaime has not stopped speaking.

One of the primary to publicize him was Daniel Tirso Fiorotto, a journalist who labored for La Nación, a nationwide newspaper.

“I knew that this was a treasure,” mentioned Mr. Fiorotto, who tracked Mr. Jaime down and printed his first story in March 2005. “I left there amazed.”

After studying Mr. Fiorotto’s article, Pedro Viegas Barros, a linguist, additionally met with Mr. Jaime and located a person who clearly had fragments of a language, even when it had eroded with the dearth of use.

The assembly marked the beginning of a yearslong collaboration. Mr. Viegas Barros wrote a number of papers on the method of making an attempt to get well the language, and he and Mr. Jaime printed a dictionary that included legends and Chaná rituals.

According to UNESCO, no less than 40 p.c of the world’s languages — or greater than 2,600 — had been below risk of disappearing in 2016 as a result of they had been spoken by a comparatively small variety of individuals, the newest yr for which dependable information is offered.

Referring to Mr. Jaime, Serena Heckler, a program specialist on the UNESCO regional workplace in Montevideo, Uruguay’s capital, mentioned, “We are very aware of the importance of what he’s doing.”

While his work preserving Chaná shouldn’t be the one case of a language as soon as thought useless all of the sudden reappearing, it’s exceptionally uncommon, Ms. Heckler mentioned.

In Argentina, as in different nations within the Americas, Indigenous individuals endured systemic repression that contributed to the erosion or disappearance of their languages. In some instances, youngsters had been crushed in class for talking a language aside from Spanish, Ms. Heckler mentioned.

Salvaging a language as uncommon as Chaná is tough, she added.

“People have to be committed to making it part of their identity,” Ms. Heckler mentioned. “These are completely different grammatical structures, and new ways of thinking.”

That problem resonates with Ms. Jaime, who has needed to overcome entrenched beliefs among the many Chaná.

“It was passed down from generation to generation: Don’t cry. Don’t show yourself. Don’t laugh too loudly. Speak quietly. Don’t say anything to anyone,” she mentioned.

For a time, that’s how Ms. Jaime additionally lived.

She shunned her ancestry as a teen as a result of she was bullied in school and scolded by academics who doubted her when she mentioned she was Chaná.

After her father began talking publicly, she helped him manage language lessons he supplied at an area museum.

In the method, she started studying the language. Now she teaches Chaná on-line to college students world wide — many are lecturers, although some say they’ve traces of Indigenous ancestry, with a small quantity believing they could be descendants of Chaná.

She plans to show the language to her grown son so he can proceed their household’s work.

Back at Mr. Jaime’s kitchen desk, the older man wrote his title out within the language he’s making an attempt to maintain alive. It was a reputation that he says displays the best way he has lived. “Agó Acoé Inó,” which implies “dog without an owner.” His daughter leaned in to verify he spelled it accurately.

“She knows more than me now,” he mentioned, laughing. “We won’t lose Chaná.”