An early scene in the coming season of HBO’s “The Righteous Gemstones” showcases the newest product in a long and somewhat troubled line of consumer goods from the fictional first family of televangelism.

These “luxury” enclosures, called Prayer Pods, offer sanctuary from the din and prying eyes of public spaces, starting at $1 a minute. “A tiny little, eensy, teensy, weensy bit of Christ when you need him the most,” says Jesse Gemstone, the oldest of the three Gemstone children.

But sales of the pod tank when word gets out that nonbelievers are using them to meet less virtuous, self-gratifying needs. On Reddit, people start calling them “squirt yurts.”

The Prayer Pod is a signature plot device from the mind of Danny McBride, the “Gemstones” creator, who also stars as Jesse, a sometimes lovable blowhard and a legend in his own mind. Like his brother and sister, with whom he constantly bickers over control of the Gemstone empire, Jesse has been handed immense wealth and privilege but somehow thinks he deserves more.

Since the show debuted in the summer of 2019, McBride has developed Jesse and the sprawling Gemstone brood into some of the most outrageous satirical characters on television. On Sunday, the story arc of the Gemstones bends toward its conclusion with the premiere of the fourth and final season and a plot twist introducing Bradley Cooper as the newest relative.

This season might be the most outrageous yet for the show, which revolves around the seemingly wholesome premise of a megachurch pastor, Eli Gemstone, who is struggling to hold his family together after the death of his wife, Aimee-Leigh, the Gemstones’ conscience. Eli, played by John Goodman with striking versatility and vulnerability, pays dearly for his inattention to the fatherly duties that don’t involve providing financial security.

But for all their repellent narcissism, the Gemstone family is still one of the more nuanced portrayals of evangelical Christianity on the big or small screen.

“It’s a parody, obviously, so you have to leave some room for them to dial it up to 11,” said Tyler Huckabee, managing editor of the progressive Christian publication Sojourners and a “Gemstones” fan who was raised evangelical. “But anybody who grew up in that world is going to feel something when they see those Sunday morning services on ‘The Righteous Gemstones.’”

As they look back on four seasons of work, “Gemstones” writers, producers and actors believe the show’s empathetic treatment of evangelical Christians is a piece of its legacy that will age well. What stands out to “Gemstones” alumni is the humanity and depth they brought to characters that Hollywood often oversimplifies or ignores entirely.

“One thing that we always think about with the Gemstones, and that we’re very careful of, is that they really do all believe in God,” said John Carcieri, one of the writers and a collaborator of McBride’s since they were in film school together in North Carolina. The writers tried to ground each season in Christian notions of redemption and forgiveness, he added.

“These characters have been in a tailspin ever since they lost Aimee-Leigh,” Carcieri said. “And hopefully by the end of these four seasons you’ll feel like, OK, this family will be able to move on.”

IN MCBRIDE’S CAREFUL OBSERVATIONS of Southern megachurch culture and American televangelism, he has taken “Gemstones” viewers on a romp through the sacred and the profane. Fans of his earlier HBO work — he is a co-creator of the cultish, madcap comedies “Eastbound and Down” and “Vice Principals” — will find it no surprise that for his first solo TV creation, he has leaned into the profane.

The Gemstone progeny are arrogant, entitled and pathologically lacking in self-awareness. Jesse is the type to ask his wife, Amber (Cassidy Freeman, straight out of Stepford with a pistol in her purse), to show cleavage when asking his father for a loan. He recoils in disgust when he finds out that his son Gideon (Skyler Gisondo) has gone to do charity work in Haiti.

“Please, son,” Jesse pleads. “Let these Catholics and liberals help these folks get their clean water.”

Jesse’s sister, Judy (Edi Patterson), erupts in violent tantrums and throws herself at unwilling men, exuding a confidence she doesn’t actually possess. One of the show’s repeated highlights is when Patterson, a gifted comic, delivers some of the raunchiest lines of comedy ever uttered by a female performer on television. The sexually confused youngest sibling, Kelvin (a high-strung Adam DeVine), is tormented by identity crises. One season he is an aspiring cult leader to a coterie of bodybuilders. The next he is enlisting a church youth group to help his “Smut Busters,” an operation that targets sex shops.

Still, even at their worst — as in Season 1 when video surfaces of Jesse snorting cocaine and cavorting with topless prostitutes — the Gemstones are not entirely amoral. Gideon, who had secretly taped his father in order to blackmail him, ultimately hesitates to follow through; it is finally through him that Jesse understands the pain his bad behavior caused his wife.

“Do you really want to make things better?” Gideon asks. “Or do you just want to make all the bad stuff go away?”

Some of the show’s abundant texture comes straight from the actors’ lives. And many of the writers, notably McBride and Carcieri, grew up in the South and were introduced as children to the region’s distinctive, multifaceted Christian culture.

McBride was raised Baptist, mostly in Fredericksburg, Va. When he was a boy, his mother taught Sunday school with puppets, and he would help her set up and break down the stage. That experience, for example, inspired him to include a puppet ministry led by Aimee-Leigh, who is played in flashbacks by a luminous Jennifer Nettles.

In an interview last month, McBride said that as much as “Gemstones” is dominated by the moral failings of characters who claim to be devoted Christians, the show was never intended to pass judgment on believers. Rather, he said, he wanted to explore the intersection of capitalism and organized religion.

“You don’t really imagine church being a business where you need to update and change things to reach the audience, to reach the customer,” McBride said. But when he was interviewing pastors as research, he grew fascinated by the business side of their work.

“I remember asking them, ‘How do you decide when it’s time to close a church?’” he recalled. “And it’s the same principles as a Starbucks. If the church isn’t growing, you move your resources out of there.”

But he knew that hypocrisy in the pulpit is a tale as old as time. And if the Gemstones were just faking their beliefs for the money, he said, they would seem reductive.

“It was more complicated that they do believe — that they are people of faith. And that their ambitions and their goals are not gelling with what their moral code is supposed to be,” McBride said.

“It isn’t even to make them sympathetic,” he added. “It’s just to make them more interesting.”

CENTRAL TO THE “GEMSTONES” story has always been the tension between celestial attainment and terrestrial temptation. Their lust for material riches can be obscene. The family owns three private jets, named “The Father,” “The Son” and “The Holy Spirit.” Eli and his children all have their own mansions on the heavily guarded family compound.

The delusional sense of entitlement the children have was an idea the writers conceived of early on — like a modern twist on the notion of divine right.

“They think, ‘We’re chosen: This is what we deserve,’” said Patterson, who acts and writes for the show. “You start playing around with that. ‘What would this do to someone?’ And then we ran downfield as fast as we could.”

Viewers may recognize Eli as an amalgam of men who led some of the country’s biggest televangelist franchises. Oral Roberts, Billy Graham, Jim Bakker, Pat Robertson and others are all reflected in the character.

Eli preaches to a 17,000-seat arena on Sundays. He co-hosts his own talk show. He leads missions to China and performs mass baptisms. His children call him “America’s Jesus Daddy.”

But the moral trade-offs Eli makes to pursue and protect his wealth always lurk under the surface, threatening to engulf him and his church.

“He’s a pretty constipated guy,” Goodman said in an interview. He added: “Inch by inch, and in small bites, one thing justifies the next. And then you find yourself in the middle of a spider web.”

One particularly heartbreaking subplot in the third season involves a Gemstone-branded line of Y2K survival supplies that bankrupts Eli’s brother-in-law (Steve Zahn) and drives him to rob a bank.

“Gemstones” episodes are full of examples of questionable business propositions done in Jesus’ name. An abandoned Christian-themed amusement park looms like a ghost on the Gemstones’ estate. It recalls Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Heritage USA, the defunct resort and water park in South Carolina that was once part of the Bakkers’ lucrative religious empire before his conviction on federal fraud charges.

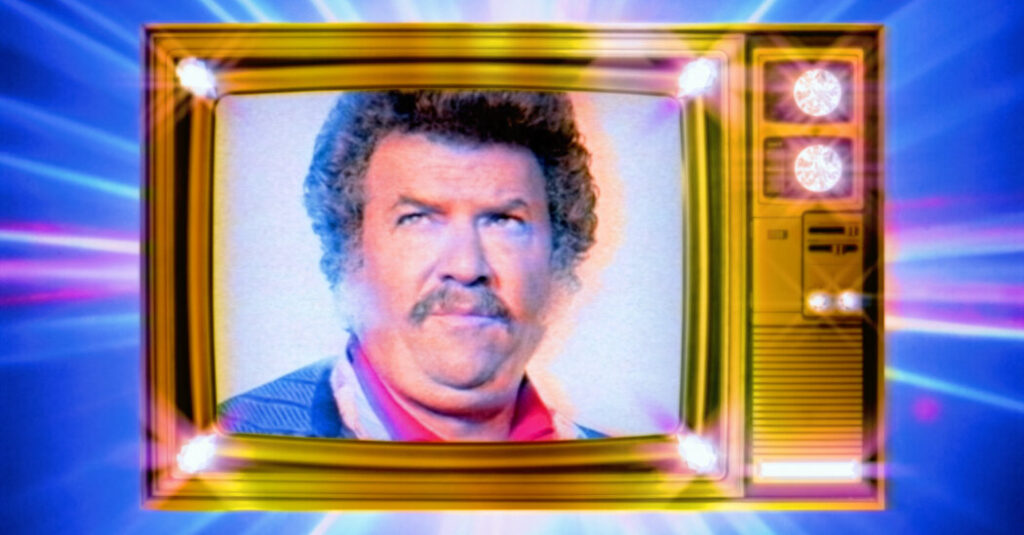

When we meet Uncle Baby Billy Freeman, played by a somewhat unrecognizable Walton Goggins — deeply bronzed, with a Colonel Sanders-like mane of white hair — his Christian cruise line has just gone belly up.

Baby Billy’s other entrepreneurial exploits have included producing a revival tour in which his dead sister, Aimee-Leigh, appears as a hologram. When Jesse balks at the idea, Baby Billy threatens to sell the hologram to a sex show in Bangkok.

Goggins, who grew up in Alabama, said the inspiration for Baby Billy came from his own father, whom he described affectionately as “a bit of a showman, with his own profound insecurities, his own narcissistic tendencies.” He credited McBride for conceiving such a brilliantly flawed character in Baby Billy — a man who, like other memorable McBride creations, suffers from delusions of grandeur but also seems just self-aware enough to know he has failed.

You want to hate Baby Billy for being unconscionably selfish, as when he abandons his young son in a mall pet store right before Christmas. But by the time he abandons his second family — ditching his much younger wife as she is about to give birth to their child — you see he does so because he thinks he could never be a good father.

“The reason why, on paper, these unsavory characters are so palatable is because of Danny McBride and the genuine affection and love he has for them,” Goggins said.

That seems to ring true, even to some evangelical Christians who might otherwise bristle at such a crude, over-the-top satire of their culture. In reviews, critics have acknowledged that the show gets something right.

“Perhaps we should consider that the way the show depicts the Gemstones,” wrote one critic for The Gospel Union, a news site that caters to evangelicals, is “closer to reality than we’d like to think.”