A new report on evictions in British Columbia, billed as the first of its kind, has painted yet another bleak picture of the province’s rental market.

Vancouver’s First United Church surveyed 443 people who had recently been evicted for everything from cause to “Landlord use,” a legal provision for cases where the landlord claims they or a close family member intends to move in.

Among the most sobering findings were how many evictees were left homeless.

Among all respondents, 27 per cent said they hadn’t found a new home. Among people of colour it was 31 per cent, while 34 per cent of people with disabilities said they couldn’t find a new home and 45 per cent of Indigenous people said they hadn’t found a new place to live.

The report also found many people were evicted informally — by text message or phone — rather than with the proper use of a legal eviction notice.

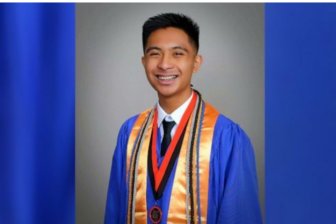

The challenges facing tenants are no surprise to Nadeem Saleh, a BCIT student with a disability who told Global News he was evicted due to a shady rental situation involving a property agent.

Saleh said he and nine other tenants believed they were renting their home from the landlord, but the person they had an agreement with was actually subletting to them from the real landlord.

In January, the group was shocked to find they were suddenly being thrown out in to the street.

“We were evicted in a very hard way and we were the victims,” he said. “Without any notice we were out on the street and our stuff was out on the street.

“I didn’t know the relation between the agent and the landlord. As someone who was subletting and paying on time, why should I be evicted without a notice because of a problem between the agent and the landlord, and why when speaking to the (Residential Tenancy Branch), I was not given any information?”

Saleh said the experience left him staying in motels until he was able to secure temporary housing at his school.

Sarah Marsden, director of systems change and legal with First United, said Saleh’s experience is yet another case of tenants being poorly served by the system.

“The cost is just so high when people get evicted. We see family separation, we see tremendous financial impacts, health impacts,” she said.

“Given how high the stakes are for tenants right now I think the strongest feeling for me is if we know it doesn’t need to be this way then why is it this way?”

Marsen said about six in 10 people the study surveyed reported being evicted under the landlord use provision.

While in many cases that eviction may be legitimate, she said many other property owners use the rule to game the system and evict tenants to try and get higher rent for the property.

British Columbia does not keep a database of evictions, and if tenants don’t challenge them there is no provincial record.

Marsden said that means the true scale of the issue is unknown, there’s no way to assess how many evictions under the provision are legal.

She wants to see B.C. adopt Ontario’s model which requires a hearing for all evictions, in which a landlord must present evidence before the tenants can be ordered to leave.

“What’s most upsetting to me is the fact a lot of this could be prevented and it’s not. We don’t know the exact numbers of which landlords use applications are valid and in good faith, we don’t have data about that,” she said.

“But we know a lot of these evictions would be preventable if we required evidence up front.”

David Hutniak, CEO of Landlord BC, told CKNW’s Jas Johal Show there are strict regulations in place to prevent abuse of the landlord use provision, including the requirement of two months notice and a rule that landlords must move for at least six months.

Breaking those rules can result in a penalty of up to 12 months rent, he said, adding that “by and large” the system works.

“There’s a regulatory framework here. We need one that allows landlords to reclaim their their their units if they or (their) child wish to reoccupy it, but also protect tenants,” he said.

“But I think one of the challenges that that has emerged here is the process, so should a tenant feel that this was not done in good faith, the process they need to go through, through the residential tenancy branch probably could be a little more straightforward.”

Hutniak said a potential fair compromise could be to amend the rule to require landlords occupy the unit for a full year, but also to expand the definition of “close family member” to include siblings, grandparents or grandchildren.

B.C. Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon told Global News the province remains committed to protecting renters from evictions, and pointed to 2021 changes protecting against “renovictions.”

Under those changes, landlords must provide evidence a renovation is needed before evicting tenants to complete the work.

He said more changes were in the works, including looking at how the landlord use provision is working — including Ontario’s evidence-first model.

“We want to ensure that landlords who are doing it for the right reasons, with just reasons, are able to still do it — but at the same time we know there are some bad actors who are using the system or abusing the system,” he said.

We’re going to try to find the balance in the coming months, we’ll be looking at ways and tools we can protect renters but at the same time ensure that landlords when they actually need the space for real reasons are able to do so.”

Saleh told Global News his temporary student housing arrangement will expire next month, and as a disabled person and an immigrant, he’s worried about what comes next.

“The housing market is very hard,” he said. “It’s becoming more scarce and it’s getting harder to get a place.”

You can read the full report here.

© 2023 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.