M. Paul Friedberg, a landscape architect whose playgrounds, pocket parks and plazas transformed once-gritty areas of New York City, using familiar urban materials to do so, died on Feb. 15 in Manhattan. He was 93.

His death, in a hospital, was announced by Dorit Shahar, his wife.

Mr. Friedberg grew up in rural Pennsylvania, but he believed in the promise of cities — their diversity and density — to create happier, healthier societies. Like his friend the sociologist William Whyte, he felt that public spaces were successful only if people used them, and that parks and plazas should be as inviting and flexible as possible.

“A wall is an obstruction, and a ledge is a place to sit,” Mr. Friedberg liked to say, quoting Mr. Whyte. He was bullish on ledges and steps, and used them often.

His early work was part of a wave of civic reform in the mid-1960s, led by Mayor John V. Lindsay and his parks commissioner, Thomas Hoving, who wanted to make the city’s parks and public spaces more inclusive and fun. When Mr. Lindsay took office, Mr. Friedberg had already designed an innovative park and playground for the Jacob Riis Houses, the public housing complex on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

He was inspired by the adventure playgrounds springing up in Europe, where designers had observed children playing in the rubble after World War II. “They realized children really didn’t need formal play environments,” Mr. Friedberg told The New York Times in 1995. “They gave children saws and drills and boxes and called them adventure playgrounds.”

For the Jacob Riis Houses, a project funded by the Astor Foundation, he created a community space shaded by pergolas and trees. There was a low amphitheater that turned into a shallow pool in the summer, with jets of water pouring down the steps. At night, it served as an open-air theater.

The Jacob Riis playground was a modernist marvel, set with wooden struts and beams, with mounds and pyramids made from cobblestones that children could climb over and crawl through. They could improvise their play, rather than having it determined for them. It was a watershed project, and a startling departure from the ethos of the fenced-in, asphalt playgrounds favored by Robert Moses.

Mr. Friedberg became the unofficial dean of the city’s experimental playground movement. For a space in Central Park at East 67th Street, he incorporated boulders of native schist into the undulating topography and a granite slide set in a rocky outcropping. In the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, in another project funded by the Astor Foundation, he made a play street, closed to traffic, with a plaza for the grown-ups, after inviting the community to cite its needs.

“His work and approach were transformational for the design of public spaces, not just in New York City, but for the landscape architecture profession,” said Mariana Mogilevich, the author of “The Invention of Public Space: Designing for Inclusion in Lindsay’s New York” (2020). “Friedberg comes into this moment where no one is attending to the urban landscape as something of value to urban residents, especially those who were poor or racial minorities,” she added. “He designed landscapes that recognized their full humanity.”

In New York and other cities across the country, he became the go-to designer for reinvigorating public space. He tucked vest-pocket parks into vacant lots and the dead space between buildings. He set plazas on top of parking garages, and playgrounds on rooftops. In Washington, he turned a traffic island on Pennsylvania Avenue into the multilevel Pershing Park. In Minneapolis, he created a tree-lined agora with pools and waterfalls and amphitheater seating. The city called it Peavey Plaza; he called it the city’s living room.

In Battery Park City in Lower Manhattan, Mr. Friedberg collaborated with the architect Cesar Pelli and the sculptors Scott Burton and Siah Armajani on the design of the World Financial Center, which already had a water feature, the Hudson River, although the group added another one: slim, black granite pools beside cafe seating on the ground level.There was also a marina, which the group was not responsible for but designed around, and which some in the community felt was elitist. Mr. Friedberg disagreed.

“I think that the people who have money have a right to have their boat,” he told Charles A. Birnbaum, the president of the Cultural Landscape Foundation, in an oral history for the foundation’s website.

“The boats animate the space for all the rest of us who don’t have boats,” he said. “And maybe someday everybody will be rich and be able to have their boat here.”

“He was serious about the idea of child’s play, and an unrepentant believer in the virtue of cities when U.S. cities were at their nadir,” Mr. Birnbaum wrote after Mr. Friedberg’s death. “He worked mostly in the public realm, which meant that everyone was his client; he knew he was responsible both to them and for them.”

Marvin Paul Friedberg was born on Oct. 11, 1931, in Brooklyn, the only son of Mary (Bennett) Friedberg and Morris Friedberg, a milk inspector. When he was 5, his family moved to rural Winfield, Pa., where he attended elementary school in a one-room schoolhouse. In high school, he worked with his father, who had started a weekend nursery business. He went on to study ornamental horticulture and art at Cornell University, graduating with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1954.

Mr. Friedberg fell into landscape architecture almost by accident. He needed a summer job, and a friend gave him an introduction to a landscape architect who assumed that Mr. Friedberg had been trained in the field because he was studying at Cornell. (After he got the job, he learned rudimentary drafting skills from sympathetic office mates.) Following graduation, he spent two years in the Army as a survey officer, stationed in Oklahoma and Korea.

Returning to New York, Mr. Friedberg set up his own business — not because of any passion for the profession, which would come later, he said, but because he thought the money was good and he had already landed his first job, designing an outdoor space for a family friend.

In the late 1960s, the American Society of Landscape Architects asked him to develop an academic program in urban landscape design, an unheard-of focus in those days, when landscape architecture was thought to have something to do with yard work in suburbia. The goal was to get urban dwellers invested in the city, and to open the profession to minorities and women. He approached the City College of New York, where he founded an undergraduate program in urban landscape architecture in 1970, serving as the director for the next 20 years.

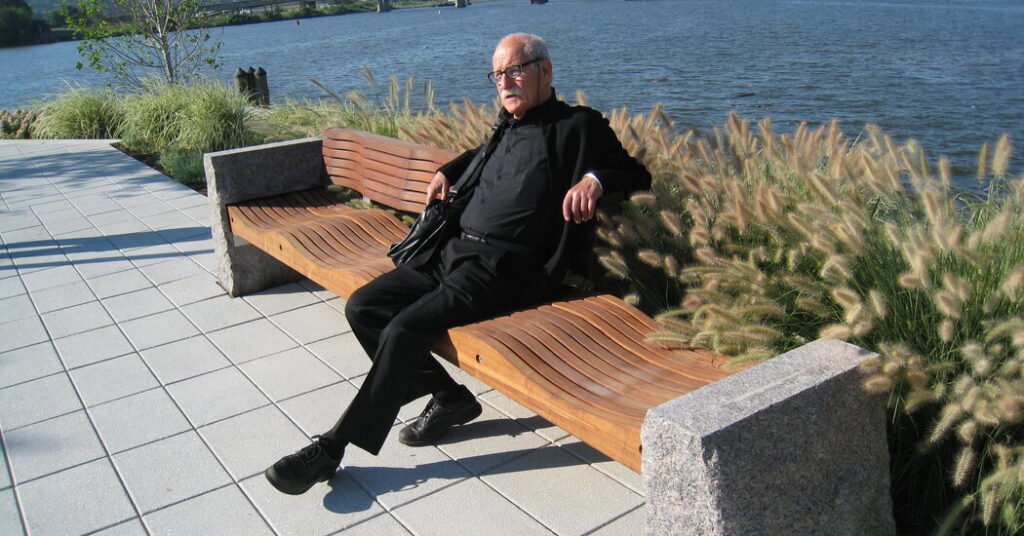

Mr. Friedberg cut a dashing figure in his signature uniform: black turtleneck, black pants and a silver bangle he was given by an Indian Sikh while working in India and Nepal in the late 1970s. (His colleague Michael Barnicle said, “In meetings, when he slammed his fist and that bracelet hit the table, you knew he meant business.”) For decades, Mr. Friedberg rode a motorcycle to job sites and meetings, terrifying colleagues who had to ride with him.

In addition to Ms. Shahar, a landscape architect with whom he opened an office in Israel, Mr. Friedberg is survived by their daughter, Maya, and his sons, Mark and Jeffrey, from his marriage to Esther Hidary, a social worker who died in 1982. He never retired.

Parks and playgrounds need care and maintenance, which requires money and civic will. Many of Mr. Friedberg’s projects have not survived, including the one at Jacob Riis. Over the years, its pyramids and mazes were replaced with play equipment that met contemporary safety standards; the trees and grass were deemed off-limits and corralled behind a high spike fence.

“I think what we do is we tend to destroy the creative side of human nature, and in play is where we are most creative,” Mr. Friedberg said in his oral history. “This is not a wasteful exercise. It is not a custodial period in life when you are waiting to get to somewhere else, but it is part of an ongoing process.”

He added: “There are people whose whole life is dedicated to play, and those are the people we call artists.”