The handshake is an honoured tradition of Kenyan politics. It signifies the coming together of seemingly intractable enemies into an agreement to share the spoils rather than fight over them. It has always been negotiated in secret between a party with state power and a rival claiming popular legitimacy and has always functioned as a ploy by the political elite to dent popular momentum towards any change that threatens to upend the country’s rigid political caste system.

It is a legacy of British colonialism. The first handshakes were doled out at the dawn of colonial rule as the British co-opted local potentates and pretenders as colonial officials, giving them the opportunity to “eat” as they sold out their people. Just prior to granting Kenya independence in 1963, the British executed another handshake, this time with the person they had scurrilously accused of leading the Mau Mau rebellion and jailed for seven years, Jomo Kenyatta. Despite labelling him a “leader unto darkness and death”, they nonetheless cut a deal with him to smooth his way into power in return for a promise to let them keep the land they stole.

In the years following independence, the handshake became the go-to tactic for managing elite contestation for power as well as popular dissent. Its cynical practicality – as veteran journalist Charles Obbo put it: “every politician has a chance to eat. Every deal is possible. No betrayal is unthinkable” – has paradoxically been responsible for preventing Kenya’s success as well as stopping the country from sliding into violence and anarchy. The handshake that ended the post-election violence in 2008 is a great example. It stopped a conflagration sparked by a dispute over the presidential election that had taken more than 1,300 lives and displaced hundreds of others. However, it also saddled the country with a regime whose first order of business was to institute a fake maize subsidy scheme that lined the pockets of politicians of all stripes and left a third of the nation starving.

One of the two protagonists in that particular episode was Raila Odinga, probably the most prolific practitioner of handshake politics. A permanent opposition doyen who has never officially won a presidential election – he was a controversial losing candidate in five of the last six elections, some of which were stolen from him – he has nonetheless succeeded in executing a power-sharing agreement with each of Kenya’s last four presidents.

These agreements have always been claimed to be in the national interest, but in reality have allowed him to leverage his popularity to access the trough. In 2000, he shook hands with former dictator Daniel Arap Moi in what many in the reform movement that was pushing for a new constitution saw as a betrayal. His 2008 handshake was with Moi’s successor, Mwai Kibaki. A decade later, in 2018, in the wake of more violence following yet another disputed election, he was at it again with then-incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta.

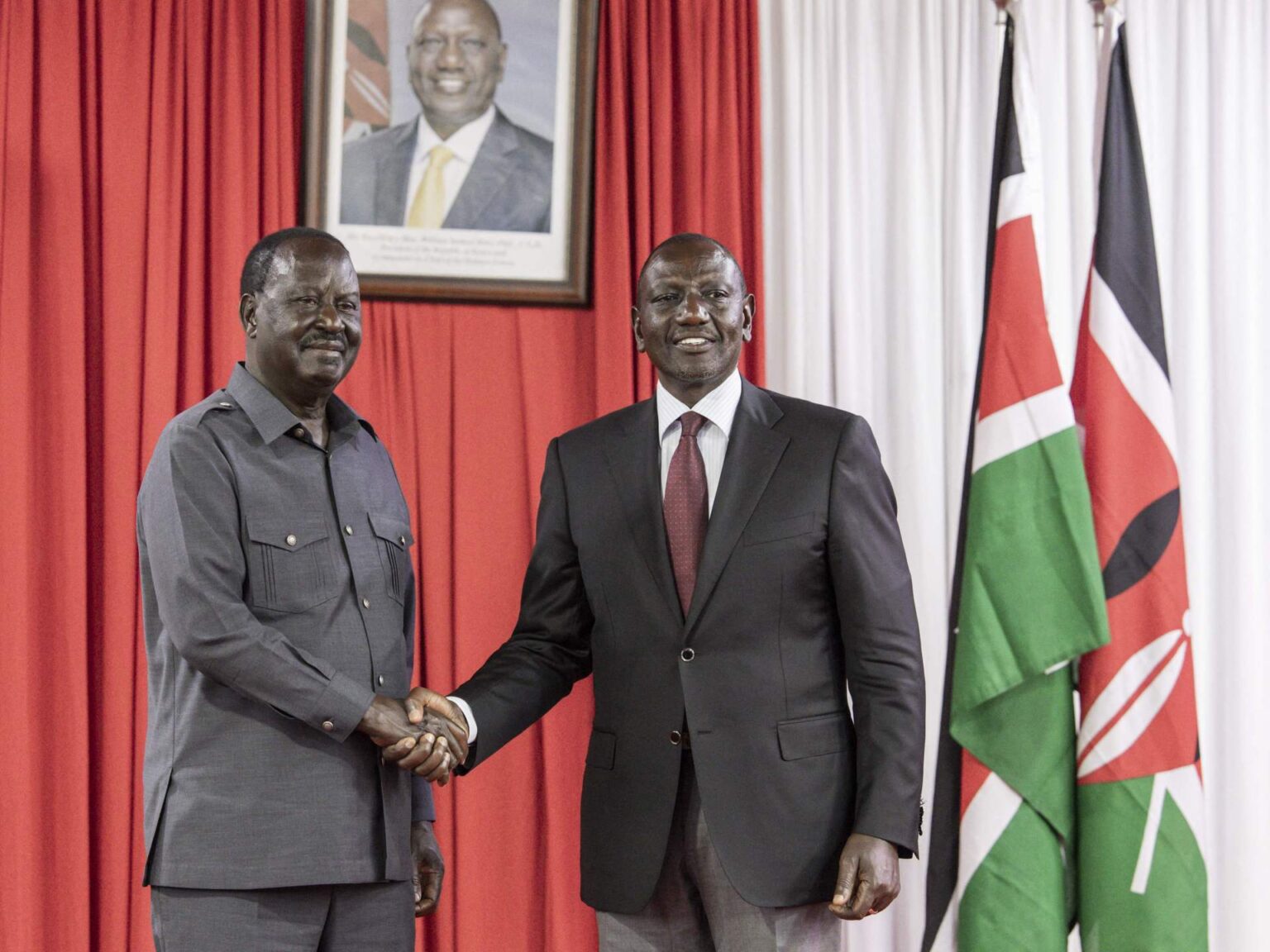

Two weeks ago came news of yet another handshake, this time in the shape of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) between Raila’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) party and current President William Ruto’s United Democratic Alliance (UDA). There are some interesting aspects to this particular deal.

First, Ruto, then deputy president, was the main casualty of the 2018 deal. At the time, it was widely perceived that Kenyatta was paving the way for the state to install Raila as his successor as president in return for quiet in his second term. In the process, he was sacrificing Ruto’s ambitions, despite having promised to support him since they got together in 2013 (that’s yet another handshake tale – the two were indicted by the International Criminal Court for being on opposite sides of the 2007 violence). However, Kenyatta eventually failed to deliver his end of the bargain.

Secondly, just like Kenyatta before him, Ruto had in 2023 ruled out a handshake with Raila, who had, following the 2022 election, been leading weekly protests to push a rather dubious case for the election having yet again been stolen from him. Despite initially gaining little traction, these protests were supercharged by the cost-of-living crisis, but still Ruto held firm.

It was not until last year’s youth-led protests, which completely sidelined the political elites, that Ruto relented, bringing members of ODM into his expanded government whilst backing Raila’s bid for the chairmanship of the African Union Commission. Following the failure of the latter effort, the MoU has now formalised the handshake.

Once again, the agreement is being framed as a response to national challenges rather than as a self-preservation measure. Odinga has claimed that a military coup was imminent if he didn’t sign on – hotly denied by the Ministry of Defence – as well as intimating that it was an opportunity to implement the report of the National Dialogue Committee.

That report, which was compiled in the aftermath of the Gen Z protests, itself illustrates just how politicians use handshakes to pad their pockets while undermining popular causes. It largely failed to engage with the issues advocated by the protesters and instead, like the National Accord and Building Bridges Initiative reports that followed the 2008 and 2018 handshakes respectively, it proposed a raft of new well-paid public positions for politicians – including prime minister and leader of opposition as a panacea to the country’s political problems.

It is unlikely that this handshake will buy Ruto the legitimacy he craves, however. Raila’s credibility as opposition leader has been eviscerated by these repeated accommodations, none doing more damage than the 2018 one. Today, he seems less like the political powerhouse of old and more like an old man desperate to cash in one last time. The real political power has shifted to a new generation that has loudly rejected the politics of handshakes, and they are gearing up for another fight.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2025/3/21/kenyas-handshake-politics-elite-self-preservation-disguised-as-compromise?traffic_source=rss