The history of slavery is filled with stories of momentous innovation and sheer resilience. One of these is how the slaves in Colombia devised ways to escape slavery through cornrows – a hairstyle resembling African pride and heritage. Cornrows, which have African origins, are now common all over the world. But this hairstyle is steeped in the history of rebellion and redemption.

Cornrows are a “style of hair braiding, in which the hair is braided very close to the scalp, using an underhand, upward motion to make a continuous, raised row.” In the Caribbean Islands, they are also known as “cane rows” to mean “slaves planting sugar cane”, and not corn.

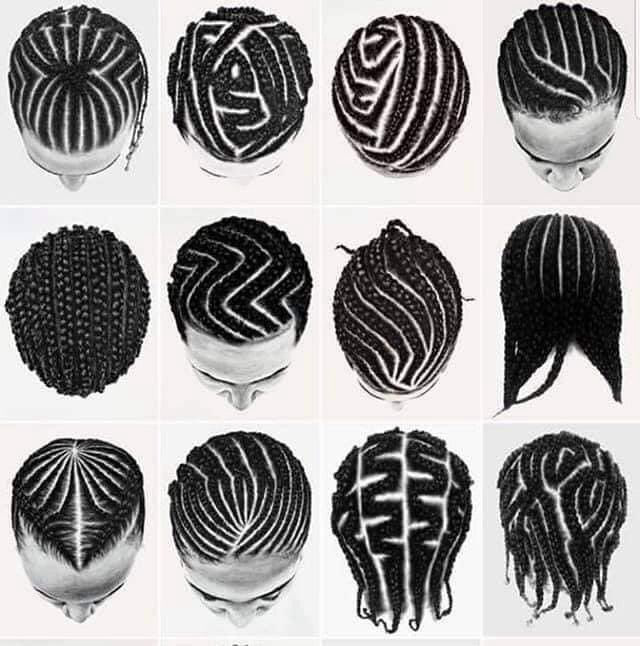

Although some cornrows are fashioned in neat linear rows, they can also be created in intricate geometric and curving designs.

They have a long history – as it is thought cornrows initially came from the Stone Age paintings in the Tassili Plateau located in the Sahara region. The usage of cornrows dates back to 3000 B.C. Another fascinating fact is that the usage of cornrows by men can be traced as far back as the early 5th century BC.

Modern depictions of males wearing cornrows occur in the 19th century Ethiopia through warriors and kings such as Tewodros II and Yohannes IV.

This hairstyle is frowned upon (even banned) in formal spaces – workplaces and educational institutions – especially in the Western hemisphere. But for people of African origin, cornrows are rich with cultural heritage and historical pride.

When millions of Africans were forcefully taken from their continent to be free labor in South America, they were subjected to brutal practices – practices created so that the enslaved African communities would feel distant from their motherland.

Many slaves were forced by their slave masters to shave their hair so that they would be more “sanitary”. The real intention was to divorce Africans from their cultural identity and heritage. These were acts done to alienate Africans from anything that resembled their identity.

Not all slaves would shave their heads. And this is how cornrows became popular among the enslaved Africans. Many would just braid their hairs tightly in cornrows. In that way, the enslaved Africans “maintained a neat and tidy appearance.”

The cornrows proved to be efficient and life-saving as they provided the African slave population with elaborate maps so that they could escape from the plantations. Cornrows were used to transfer and create maps with the intention to leave the home of the captors. Such a method for escaping was easy to hide from the slave masters. The act of using hair as a tool for rebellion was also spread to other parts of South America that had African slave populations.

Benkos Bioho, a king captured by the Portuguese from Africa, managed to escape and went on to build a new village and community. He built San Basilio de Palenque, a village in Northern Colombia around the 17th century. With the help of other slaves, they created their own language, formed their army, and created an intelligence network to find and get them to liberated areas.

In doing all this, Benkos came up with the idea that women had to create maps and deliver messages through their cornrows. Slaves were not allowed to be literate, so they had to pass information through cornrows.

Even if they had been able to read and write, there was a high risk that if the wrong information ended in the hands of the slave masters it would be catastrophic for them. With cornrows, the slave masters had no chance of deciphering the information passed among the slaves. It simply did not occur to them that entire maps could be hidden in hairstyles.

An Afro-Colombian woman, Ziomara Asprilla Garcia, explained to The Washington Post about how hair braiding was used to relay messages. For instance, women would braid a hairstyle called “departes” as a signal for escaping.

“It had thick, tight braids, braided closely to the scalp, and was tied into buns on the top,” she said.

“And another style had curved braids, tightly braided on their heads. The curved braids would represent the roads they would [use to] escape.”

“In the braids, they also kept gold and hid seeds which, in the long run, helped them survive after they escaped.”

She said that the message in the women’s cornrows “was the best way to not give back any suspicion to the owner. He would never figure out such a hairstyle would mean they would escape.”

The city of San Basilio de Palenque still exists. Being the first free African town in the Americas, it was declared a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2005. It has a population of about 3500 people.

The legacies of colonialism resulted in African hair being despised. Modern black women are barraged with notions that depict their natural hair as inferior. Africans should stand tall and be proud of their hair, for it is enriched with the history of self-assertion.