In the late 1950s, Norwegian toymaker Asmund Laerdal received an unusual brief: to design a life-like mannequin that resembled an unconscious patient.

Peter Safar, an Austrian doctor, had just developed the basics of CPR, a lifesaving technique that keeps blood and oxygen flowing to the brain and vital organs after the heart has stopped beating.

He was eager to teach it to the public, but had a problem – the deep chest compressions often resulted in fractured ribs, which meant practical demonstrations were impossible.

It was in his search for a solution that he was introduced to Laerdal, an intrepid innovator then in his forties who possessed extensive knowledge of soft plastics, honed through years of work with children’s toys and model cars. He had even begun to collaborate with the Norwegian Civil Defence to develop imitation wounds for training purposes.

Laerdal, who had rescued his son from drowning by applying pressure to his ribcage and pushing water out of his lungs just a few years earlier, was eager to help, and the two decided to create a training model.

The Norwegian toymaker had a vision: It needed to look unthreatening, and assuming that men would not want to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on a male dummy, it should be a woman.

So he went looking for a face.

The unknown woman of the Seine

It was on the wall of his parents-in-law’s home in the picturesque Norwegian city of Stavanger that he found it.

It was an oil painting of a young woman, her hair parted and gathered at the nape of her neck. Her eyes were closed peacefully, her lashes matted, and her lips curled in a faint, sorrowful smile.

This was a face which, in the form of a plaster cast, had adorned homes across Europe for decades.

There are many rumours as to how the original mask was created, but one story that has cemented itself as urban legend is that it was of a woman who had supposedly drowned in the Seine River in 19th-century Paris.

In the French capital at the time, it was common for the bodies of the deceased who could not be identified to be placed on black marble slabs and displayed in the window of the city’s morgue situated near Notre Dame Cathedral.

The purpose of this practice was to see if any members of the public would recognise the deceased and be able to provide information about them. Yet, in reality, it became a morbid attraction for Parisians.

As the story goes, a pathologist, struck by her beauty and serene expression, commissioned a sculptor to produce a death mask of her face, a plaster or wax mould of a person made shortly after death.

No documents survive in the Paris police archives, and it is impossible to verify the truth of this story.

However, a sculpture of the supposed death mask captured the public’s imagination, and reproductions of it began to circulate in the early 20th century.

Her face soon decorated Parisian salons and wealthy people’s homes.

The visage was known as L’Inconnue de la Seine – the Unknown Woman of the Seine – and it became a muse for writers, poets, and artists.

The French writer Albert Camus called her the “drowned Mona Lisa”, while the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke said of her serene expression, “It was beautiful, because it smiled, because it smiled so deceptively, as if it knew.”

Resusci Anne

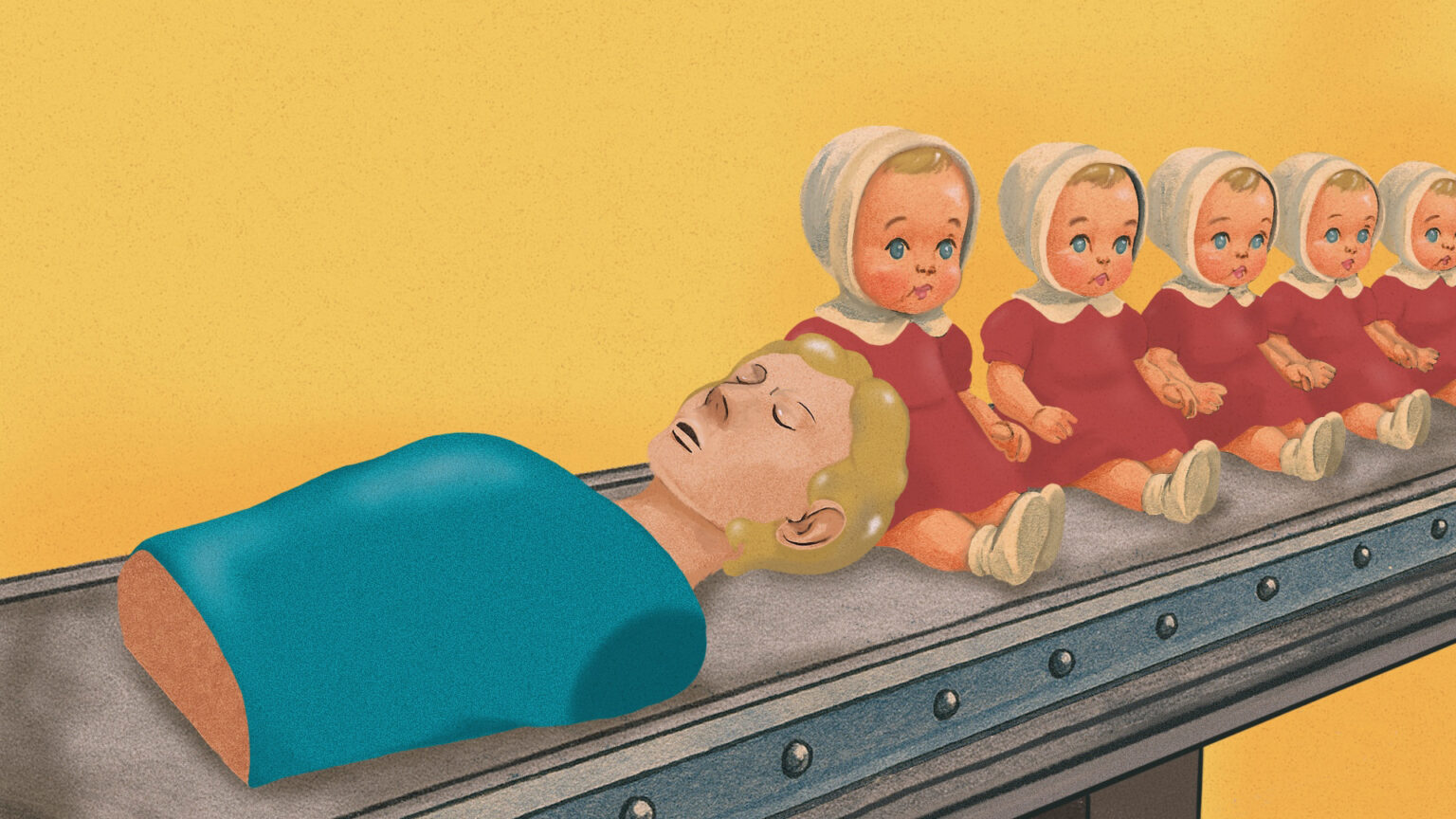

It is not known whether Laderdal was aware of the legend behind the painting in Stavanger, but in 1960, he gave it new life when the first CPR doll was officially launched with the subject’s face.

The doll was given a soft plastic torso – a compressible chest for practising CPR – and open lips for mouth-to-mouth rescue.

She travelled around the world, appearing in fire stations, schools, hospitals, scout groups, and airline training centres, where she was used for CPR training.

She was also finally given a name, “Resusci Anne,” by Laerdal, a shortening of the word “resuscitation”. Anne is a common female name in Norway and France, which suggests that by this stage, the toymaker was aware of the legend behind the face. In the English-speaking world, she became known as “CPR Annie”.

“Annie, are you OK?” became the go-to training phrase as people simulated how to check for responsiveness in the event of a cardiac arrest.

In the 1980s, about a century after Annie was reported to have been found in the Seine, Michael Jackson immortalised her in pop culture.

As the story goes, the superstar heard the phrase during a first aid training session and, struck by the rhythm and urgency of it, worked it into the chart-topping song, Smooth Criminal, repeating it like a heartbeat: “Annie, are you OK? So, Annie, are you OK? Are you OK, Annie?”

‘She would be proud’

Laerdal died in 1981, but the company he founded, Laerdal Medical, continues to be a juggernaut in emergency medical training and the development of cutting-edge healthcare technology.

Annie herself has received technological upgrades, including flashing lights, lung feedback, and sensors that indicated if compressions were off-rhythm.

But her face stayed the same.

Pal Oftedal, director of Corporate Communications at Laerdal Medical, says that regardless of whether the story behind Annie is true, she has had a positive impact on engaging people worldwide in the lifesaving practice of CPR.

He said that one in 20 people would witness a cardiac arrest in their lifetime, with 70 percent occurring outside the home.

The American Heart Association says that immediate CPR can double or even triple a person’s chance of survival after a cardiac arrest.

Annie has been joined by a new selection of mannequins featuring a range of ethnicities, ages, body types, and facial features as Laderdal seeks to diversify its product offerings.

Laerdal Medical estimates that Annie and her fellow resuscitation mannequins have been used to train more than 500 million people worldwide.

Oftedal says that he believes whoever Annie was, he is sure “she would be proud of the important contribution she has made to the world”.

This article is part of ‘Ordinary items, extraordinary stories’, a series about the surprising stories behind well-known items.

Read more from the series:

How the inventor of the bouncy castle saved lives

How a popular Peruvian soft drink went ‘toe-to-toe’ with Coca-Cola

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2025/8/9/how-a-drowning-victim-became-a-lifesaving-icon?traffic_source=rss