Xavier Becerra, the man President Biden chose to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, does not want to talk about Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the man President-elect Donald J. Trump has chosen to “go wild” in reshaping it. Nor does he have any regrets over the pandemic policies that helped seed the rise of his potential successor.

In a wide-ranging interview last week, Mr. Becerra said Mr. Biden’s coronavirus vaccine mandates, for federal employees, health care workers and large employers, were “absolutely” warranted. “Should we require people to wear seatbelts?” he asked.

That argument — that government has a right to intrude on personal liberty when the health of its citizens is at stake — lost out in last year’s elections. As a presidential candidate, Mr. Kennedy campaigned aggressively against vaccine mandates; the Supreme Court blocked the large employers mandate. Mr. Kennedy also sued Mr. Becerra’s department over its efforts to tamp down misinformation on social media. Voters responded enthusiastically when he merged his campaign with Mr. Trump’s.

On Friday, Mr. Becerra made what amounted to his farewell to Washington, announcing that Medicare, the government insurance program, will negotiate lower prices for the blockbuster weight-loss drugs Ozempic and Wegovy, and more than 20 other prescription medications. On a conference call with reporters, Mr. Becerra called the negotiations “a big deal.”

But in the interview, he acknowledged that voters did not reward Mr. Biden, or Vice President Kamala Harris, for their administration’s health care achievements, including lowering drug prices; expanding the number of Americans who have health insurance; starting a suicide-prevention hotline; and taking steps to protect abortion rights in the aftermath of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade.

“People put their attention where they need to — their family, their work, getting ahead,” he said, reflecting on the election. “They see the price of eggs. They see the price of gas. They don’t like it.”

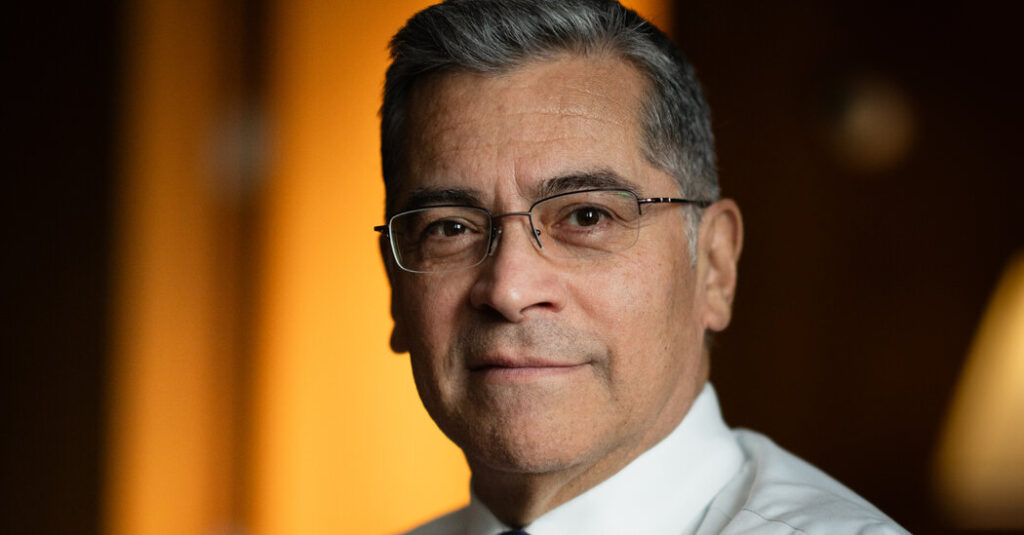

Seated at a long wooden conference table in his eighth-floor office overlooking the Capitol, Mr. Becerra seemed relaxed and at ease. A former congressman and attorney general of California, he was also the nation’s first Latino health secretary. He said he intended to return to his home state — and hinted that he may run for governor.

Without mentioning Mr. Kennedy by name, he delivered a warning to whoever sits next in his chair.

“If they contradict the science, whether it’s on vaccines or the value of public health or in reaching out to communities that have been underserved for the longest time, I think the consequences are going to be pretty clear,” Mr. Becerra said, adding, “We’ll have more unnecessary death, we’ll have more illness.”

Mr. Becerra did not make a splash as health secretary; he has cut an unusually low profile compared with some of his predecessors. Other health officials, notably Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, who retired in 2022, often eclipsed him — and became targets of Republicans in the process.

Mr. Becerra strongly suggested that Mr. Biden not give a pre-emptive pardon to Dr. Fauci, who has been the subject of Republican attacks and an unflattering book by Mr. Kennedy. Speaking as a former attorney general, Mr. Becerra said, he thought the pardon process should not be used “in a way that will follow the whims of whoever’s in the White House.”

As to Mr. Kennedy’s newly adopted slogan — “Make America Healthy Again” — Mr. Becerra said the nation is healthier than it was under Mr. Trump. He noted that on the day Mr. Biden took office, more than 4,000 Americans died from Covid-19.

“That’s like 10 jumbo jets going down a day,” Mr. Becerra said. “So when people ask me, at least when it comes to health care, ‘Are we better off today than we were four years ago?’ Absolutely. ‘Are we a stronger and healthier nation?’ Absolutely.”

But on one matter — the American diet — Mr. Becerra sounded a lot like Mr. Kennedy, who has railed against the agriculture industry and ultra-processed foods. Mr. Becerra said his department was working to address that issue through its Food Is Medicine program, aimed at reducing nutrition-related chronic diseases.

“We eat more processed food than any other nation per capita,” Mr. Becerra said. “I think we consider a Big Mac a meal. We put more salt in our snack food than they do in Europe. So you buy a bag of Lay’s potato chips here in the same bag, and Europe has about two-thirds the salt. So we need to do a lot of things to be healthier, including eating better foods.”

In some respects, Mr. Becerra may have been the right health secretary at the wrong time. His strong suit is health care affordability and access; he helped write the Affordable Care Act when he was in Congress. As attorney general, he sued the Trump administration more than 100 times over its implementation of the law, which created the insurance program known as Obamacare. Enrollment in the program roughly doubled during his tenure.

He has also been a fierce supporter of abortion rights. He is a father of three grown daughters, and his wife is an obstetrician-gynecologist who handles high-risk patients. On the day Roe was overturned, Mr. Becerra was at a Planned Parenthood clinic in Missouri, which immediately stopped performing abortions.

But Mr. Becerra became defined by the crises he inherited: a surge of unaccompanied minors crossing the nation’s southern border, and the coronavirus pandemic, which had already killed half a million Americans by the time he took office in March 2021.

His early tenure was rocky. His department was responsible for housing migrant children, whose emergency shelters — cold, detention-like facilities — became an embarrassment to Mr. Biden. Mr. Becerra took much of the blame. The response to Covid-19 was largely run out of the White House. Mr. Becerra was not often seen. Mr. Becerra said that arrangement was set by the time he was confirmed by the Senate.

He also conceded he faced challenges, in particular tamping down misinformation on social media. He sounded dismayed that Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive of Meta, Facebook’s parent company, has decided to end its fact-checking operation on social media posts.

“That’s the world we’re coming to, isn’t it?” Mr. Becerra asked. “Now you understand why it’s so tough to convince people to get vaccinated” He added: “I don’t have a budget, like a pharmaceutical company, to advertise what I do or to fight back against disinformation. It makes it very difficult, and its unfortunate.”

To critics who say he was an absentee leader, Mr. Becerra says he was simply keeping his head down, working on the “execution” of policies on an array of issues beyond Covid-19, including the high cost of prescription drugs and protecting the right to abortion.

“He hasn’t left a deep legacy of leadership on key questions,” said J. Stephen Morrison, director of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “There were major innovations that happened through White House leadership and legislative action and he was part of that, obviously, and he deserves some credit, but I don’t think he was the front edge of the spear. His leadership style was somewhat quiet.”

But Dr. David Kessler, a former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration who oversaw the Biden administration’s distribution of Covid vaccines, said Mr. Becerra’s contributions, often unheralded by the press and the public, were important.

He became a “very strong advocate of the president’s progressive health agenda,” Dr. Kessler said. “Another person would not have even survived. It was very intense, it was very rocky, it wasn’t of his making.”

Mr. Becerra was coy about his own future in electoral politics. The 2026 race for California governor is going to be wide open, with a hotly contested Democratic field that could include high-profile candidates like Ms. Harris and Katie Porter, a former congresswoman. Mr. Becerra demurred when asked about his plans.

“Ask me after the 20th,” he said, referring to Mr. Trump’s inauguration day. He was smiling.