When the biotech company Humacyte designed a study to see if its lab-grown blood vessel worked, it decided to measure whether blood was flowing freely through the high-tech tube 30 days after it was implanted in a person.

As those days passed, some of the 54 patients in the study ran into trouble. Doctors lost track of one. Four died. Four more had a limb amputated, including one who developed a clot and infection in the artificial vessel, Food and Drug Administration records show.

Humacyte, which is traded on the Nasdaq, counted all those patients as proof of success in talks with investors and in an article in JAMA Surgery.

At the F.D.A., though, scientists counted the deaths, amputations and the lost case as failures, records show, noting a lack of information to determine if the vessels were clear.

Still, the agency approved the vessels in December without a public review of the study. Top officials authorized it over the concerns of staff members who said in F.D.A. records that they found the study severely lacking or were alarmed by the dire consequences for patients when the vessels fell apart.

Now the company is ramping up its marketing efforts to hospitals and for use on the battlefield.

When a patient’s blood vessel is damaged, doctors typically find a blood vessel from another part of the body and graft it to repair blood flow. They turn to artificial vessels when patients are too badly injured to harvest a vein.

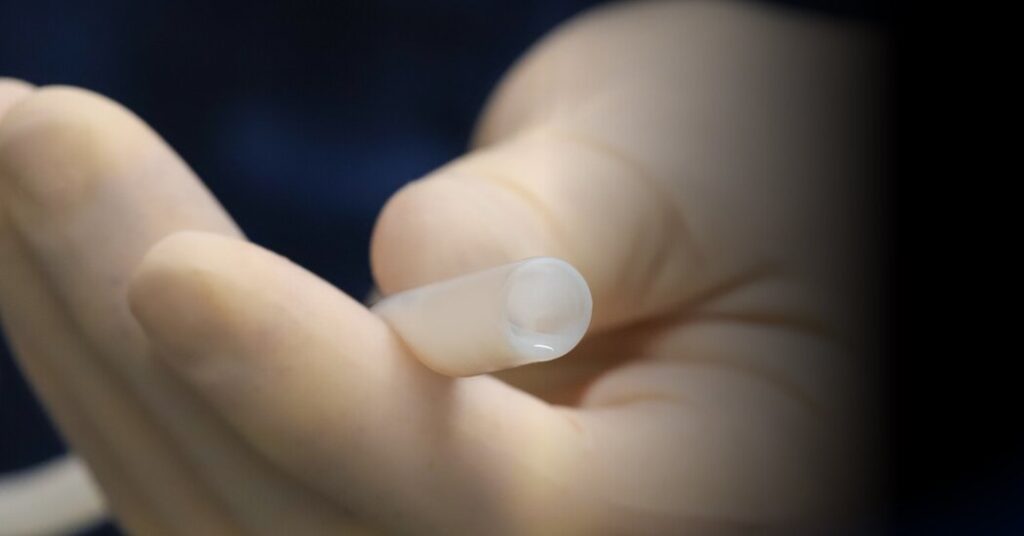

The Humacyte vessel is made from a mesh tube seeded with cells from the human heart. The cells grow over two months in a bioreactor, and at the end of the process, the human cells and genetic material are removed. A lab-grown tube, mostly made of collagen developed from the aortic cells, remains.

Before the vessel was approved, one F.D.A. medical reviewer pointed out that 37 of the 54 patients were not assessed in a safety check four months after getting the implant, with many dead or lost to follow-up. “There is significant uncertainty regarding the safety and effectiveness of this product beyond 30 days,” the F.D.A. report says.

Dr. Robert E. Lee, a vascular surgeon who cared for gunshot-wounded patients in Detroit for 30 years, retired in the fall from the F.D.A. in protest over the matter. In a review of more than 2,000 pages of company records conducted when he was an F.D.A. medical officer, Dr. Lee found that the vessel could rupture with no warning. Those events were “unpredictable, catastrophic and life-threatening,” he wrote in his F.D.A. review, parts of which were made public weeks ago.

“That’s an unacceptable risk for whatever slim benefit, if any, this product provides above the current standard treatments,” Dr. Lee, who had been a reviewer at the agency since 2015, said in an interview. He noted that doctors currently use the patients’ own vessel, if available, or tubes made of Gore-Tex.

An F.D.A. spokeswoman said the approval “was based on a careful evaluation of data from clinical trials that demonstrated a clinically meaningful benefit in restoring blood flow in the affected limb and ultimately limb salvage.”

Humacyte is also developing a graft for patients with dialysis, for those undergoing cardiac bypass surgery and for infants with a heart-related birth defect.

Dr. Laura Niklason, one of the company’s founders, said approval of the vessel, called Symvess, was a “milestone for regenerative medicine overall.”

She had begun work to create the lab-grown vessels decades earlier. In its 20 years, the company had logged no sales and accrued more than $660 million in debt, financial reports show.

In an interview, Dr. Niklason said the disagreement over how to label the patient deaths and amputations as successes or failures arose after the company decided to count cases as failures only when it was certain that blood flow was cut off. The F.D.A. took a more conservative approach to calculating the success rate for the product, she said. “Rational people can disagree,” she added.

The F.D.A. records do not indicate whether the problems with the vessels directly caused the deaths or amputations.

Dr. Niklason said that the company must use the agency numbers in marketing the product to clients but that it could present its more favorable figure to investment analysts. She also said the study was published before the F.D.A. reached its decision.

B.J. Scheessele, the company’s chief commercial officer, told investors this month that Humacyte was in talks with 26 hospitals to begin distribution. Mr. Scheessele also said the company was hoping to sell the vessels to the Defense Department for battlefield injuries. The U.S. Army gave Humacyte $6.8 million in 2017, embracing the product as an option for wounded soldiers.

Each artificial vessel costs $29,500, and Mr. Scheessele said the company hoped to market several thousand each year in the United States.

Dr. Niklason said in an interview that her interest in engineering a blood vessel was twofold. As young doctor, she had observed that arterial disease was devastating.

She described an experience as a medical resident in the late 1990s watching a senior doctor make incision after incision in a patient’s legs and arm, seeking a healthy vessel to use in a heart bypass surgery. She called the procedure “barbaric.”

“To provide a new blood vessel for a patient who needs one, we usually have to rob Peter to pay Paul,” she said.

Since Dr. Niklason first began meeting with the F.D.A. in 2015 about starting a trial in humans, the agency repeatedly found fault with the company’s efforts to study the vessel’s use. Its trial involved people suffering major trauma, such as gunshot or car crash injuries, took place in U.S. hospitals and in Israel. The participants had an average age of 30, and half were Black patients.

Humacyte also provided the vessels to doctors treating injured soldiers in Ukraine.

By Nov. 9, 2023, Dr. Niklason described results of the studies to investors on an earnings call in glowing terms. Initially, she said the rate of blood flow through the vessels at 30 days was 90 percent — beating existing products on the market.

And the results in Ukraine were “remarkable,” she said. “We’re proud to be able to help our Ukrainian surgeon colleagues save life and limb in this wartime setting.”

Over the ensuing months, though, reviewers at the F.D.A., including Dr. Lee, would examine the same studies and conclude that they did not look nearly as good.

As a vascular and general surgeon in Detroit, Dr. Lee had decades of experience with victims of gunshots, stabbings, car crashes and other accident victims who might receive such vessels.

He said he was alarmed by the account of a man in Ukraine who began bleeding at the site of his surgical wound eight days after the vessel was implanted. Doctors discovered a two-millimeter hole in the Humacyte vessel and repaired it with sutures, according to F.D.A. records. Four days later, the patient was bleeding again, requiring removal of the graft the next day. The review suggested that an infection could have played a role.

Of 71 cases that Dr. Lee examined for a safety review, seven people, or about 10 percent, experienced vessel failures that resulted in major bleeding, according to the F.D.A. review. Dr. Lee said that was unheard-of in his experience with Gore-Tex grafts.

“Plastic arteries, they don’t usually present with catastrophic hemorrhage, unexpected like this,” Dr. Lee said. “You know the patients are sick,” with a fever or other signs of an infection, he continued. “You know something’s brewing, and you usually have time to take care of it.”

Hoping to glean more information about the root cause of the mid-vessel blowouts — and to be sure doctors were aware of the possibility — Dr. Lee began seeking a public advisory hearing on the device.

Thomas Zhou, a biostatistician in the biologics division of the F.D.A., also flagged concerns from the U.S. arm of the study and the data from Ukraine.

“Neither study met the usual criteria for an adequate and well-controlled trial,” he wrote.

The study of 16 patients treated in Ukraine was retrospective and observational, meaning researchers could look back at a larger pool of data and select the best cases. It showed “limited support of efficacy,” partly because the injuries were “skewed to shrapnel injuries” and not the devastating wounds typically seen on the battlefield, he said.

The U.S. study was “poorly conducted” and underwent “multiple major changes” during the trial, the statistical review said.

The records also show that F.D.A. scientists dismissed as successful the patient deaths and amputations, citing a lack of information or imaging studies.

As a result, the F.D.A. concluded that the vessel’s success rate for that key study was 67 percent, rather than the company’s 84 percent, F.D.A. records show. In comparison, artificial grafts already had blood flow rates of 82 percent, the review said.

The company also reported an 84 percent success rate at 30 days in an article published in November in JAMA Surgery, which is widely read by surgeons. The article stated that the Humacyte vessel “demonstrates improved outcomes” over other artificial vessels.

It also said the Symvess “provides benefits” in “infection resistance.” The F.D.A. review said there was no clinical evidence demonstrating that extra effect.

Dr. Lee failed to persuade top F.D.A. officials to hold a public advisory committee meeting where the study results could be discussed and reviewed by independent experts. The agency decided instead to send records to three external reviewers, who in turn identified failure of the Humacyte vessels “as a serious risk,” but added that “the appropriate patient population” would benefit, according to documents.

In announcing approval of the graft on Dec. 20, Dr. Peter Marks, head of the biologics division, called the vessels “innovative products that offer potentially lifesaving benefits for patients with severe injuries.”

But the product is accompanied by a black box warning — the agency’s most serious — for failures that “can result in life-threatening hemorrhage.” The F.D.A. also is requiring the company to continue reporting safety data.

Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, co-director of the Amy J. Reed Medical Device Safety Collaborative at Northeastern School of Law, said the F.D.A. should not have approved a product that its scientists deemed inferior to existing options.

“If the graft falls apart,” he said, or if it disconnects to where it is attached to the vessel, “it is basically akin to the patient getting shot.”

Dr. Lee said he hoped the F.D.A., with new leadership under the Trump administration, would still hold a public meeting.

“Every surgeon who uses it needs to see the things that I did,” he said.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/24/health/fda-artificial-blood-vessel-trauma-humacyte.html