Among the plethora of art fairs this week in New York City, there is still only one dedicated to contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora. The 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair was founded in 2013 by Touria El Glaoui, a former telecom salesperson raised in Morocco by an artist father and a French mother, who noticed a gap in the market where local artists were being ignored by the mainstream. The exposition follows El Glaoui’s own trajectory, making yearly presentations in Marrakesh, New York and London.

It has also traversed New York in the last decade, from Red Hook to Harlem and Chelsea, and now to the financial district.

It has consistently rewarded me with surprising, inventive booths and installations. This year is a slightly more focused fair, with 28 galleries and two special installations (there are over 70 artists in all), compared to 32 galleries last year, but there is no less extravagance and panache.

One of the most exciting booths is the presentation by Tern Gallery, from Nassau in the Bahamas. It primarily shows Bahamian artists but is currently featuring a Jamaican-born expatriate artist: the painter Leasho Johnson. His paintings, including “Black and Up to No Good (Anansi #23)” from 2023, roil and twist around what may be a central figure on a yellow boat crossing a body of water. But this is guesswork. Johnson’s abstractions flirt ruthlessly with narrative and representation. I could spend hours trying to unpuzzle his visual paradoxes.

Kates-Ferri Projects (Booth 07)

This gallery presents three artists who all use texture in ways that are marvelously inviting. The Brooklyn-based Ashanté Kindle offers iridescent hues of acrylic paint to suggest the waves of Black hair and sometimes includes hair knockers, barrettes and beads to seal the deal. The Nigerian artist Samuel Nnorom uses small balls of brightly colored Ankara fabric to create constellations of celestial bodies that are much closer to the touch. Jamel Robinson applies paint in one of the most combative ways possible: He uses boxing gloves dipped in acrylics to punch and pummel the canvas, producing a visual record that’s a flurry of spent energy.

Kub’art Gallery (Booth 16)

At this gallery from the Democratic Republic of Congo, look for the manipulated photographs of Prisca LaFurie Munkeni Monnier, who adorns her subjects’ skin with ornate jewelry, ritual scars and wild animal limbs. The work is both excruciating and haunting. In a photo titled “Hostie Noire” (2022), the figure’s skin seems to be gathered in folds that are pierced by rusty nails.

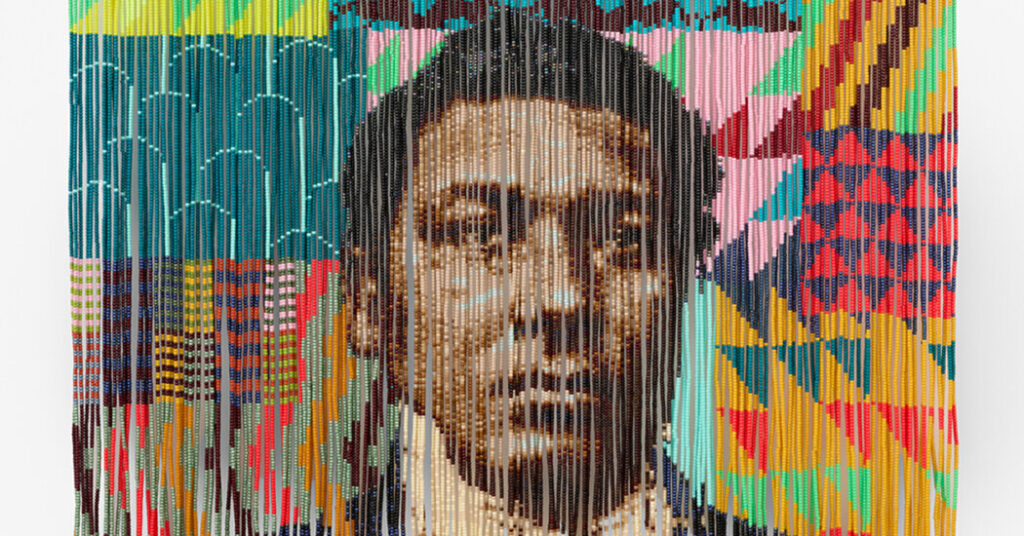

The body takes on other, poignant textures in the beaded curtain work of the artist Felandus Thames, who lives and works in New Haven, Conn., shown at this gallery based in Paris. The figures are vividly bright in these pieces, with fulsome lips and piercing gazes but also edging toward insubstantiality, as if a stiff wind could partly erase them. Thames’s “African King of Dubious Origins #6,” (2022) is both garish and beautiful. Also at 193, the Nairobi- born photographer Thandiwe Muriu makes images that are so stylistically evolved that it seems she is visiting us from a future moment when one’s dress, hair, makeup, jewelry and clothing are arranged for a daily red carpet stroll.

Fridman Gallery (Booth 26)

Wura-Natasha Ogunji, an American-born artist of Nigerian descent who is based in Lagos, shows her paper collages at the Fridman Gallery in New York. Typically, pastiches made by other collagists feature human faces with exaggerated eyes or mouth and distended jaws, but Ogunji makes the legs the central motif in “Bird” (2024), where bodies that are a mix of disparate colors and patterns bend almost Chagall-like, appearing to kiss another form while running from it at the same time. It’s just an elegant comment on the contradictory nature of the way we love other humans.

1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair

Through Sunday, the Halo, 28 Liberty Street (entrances are via Pine Street and William Street), Lower Manhattan; 1-54.com/new-york.