Amsterdam prospered as a banking center even as it declined as a center of manufacturing and commerce. By the late 18th century, Europe no longer wanted Dutch fabrics or Dutch fish, and it no longer needed Dutch ships. In 1783, a group of Dutch merchants sent a gift of salted herring to George Washington, requesting his endorsement and, presumably, seeking a new market. Washington responded that the herring was “undoubtedly of a higher flavour than our own,” but that America had plenty of fish. What remained in demand was all the money the Dutch had made from trade. The merchants and princes of Europe flocked to Amsterdam to negotiate loans. The following year, 1784, the fledgling American government joined them, arranging to borrow 2 million florins.

But prosperity increasingly was concentrated in the hands of an elite. Amsterdam, and its satellites, no longer needed as many workers. The population of Holland actually shrank in the 18th century, even as much of Europe experienced a population boom.

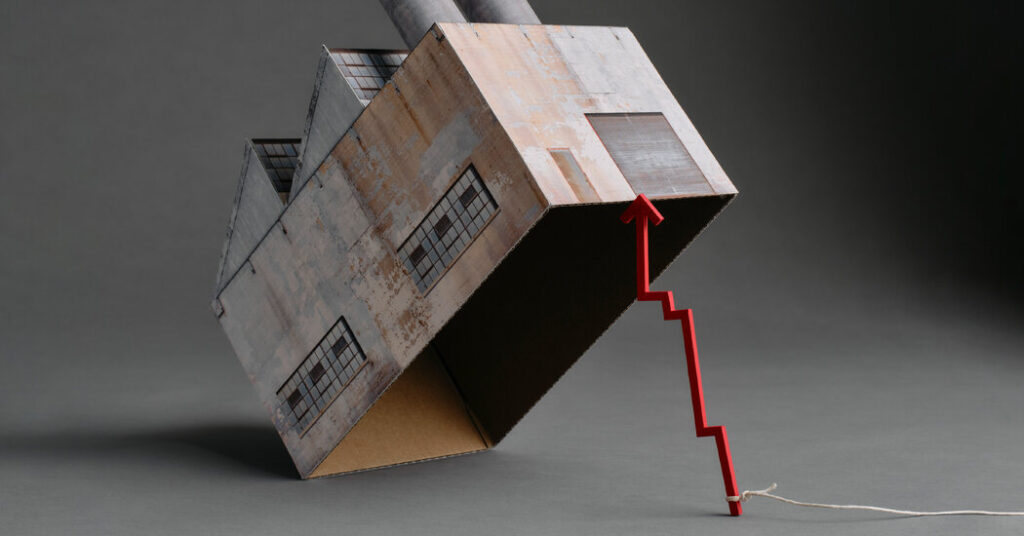

Moreover, Amsterdam’s pre-eminence as a financial center did not long survive the end of its hegemony as the center of European commerce. In the city’s heyday as a trading port, it shook off financial upheavals. Commerce was the main event; even the indelible spectacle of the tulip bubble in the 1630s was just a sideshow. But as the city’s economy became more dependent on finance, it become more vulnerable. One historian has calculated that by 1782, half of Amsterdam’s capital had been lent to foreigners. Instead of financing its own development, Amsterdam was betting on other countries, and it started losing too many of those bets. A culminating blow came in August 1788, when the French government of King Louis XVI, on the verge of collapse, defaulted on its debts. As Amsterdam’s economic power declined, so did its political autonomy. During the final two decades of the 18th century, the Dutch state descended into civil strife and endured humiliating defeats at the hands of the British and the French. In 1810, Napoleon annexed Holland to his empire.

Braudel focused on the long run of history precisely because he didn’t want to make too much of short-term pain or setbacks. It was an approach that he said he developed to maintain his equanimity during the five years that he spent in German prisoner-of-war camps during World War II, refusing to make too much of “daily misery” or the latest scraps of news. And in his view, what was most significant about Amsterdam’s life after hegemony was not the turbulence in the immediate aftermath, but the long-term resilience of the Dutch economy. Amsterdam never fell that far, and what Braudel wrote in 1979 remains true: “It is still today one of the high altars of world capitalism.”

The arc of London’s story is much the same. It is not a city anyone would think to pity. The United Kingdom and the Netherlands have plenty of problems, of course, but each remains among the most prosperous nations on Earth. It’s important to note, however, that Amsterdam had the good fortune to cede its supremacy to a city, and a nation, that shared many of its basic values. Indeed, Braudel observes that Amsterdam lost its supremacy in part because some of the richest Dutch merchants preferred to live in London, a Protestant, capitalist city they regarded as more fun. London, in turn, yielded to a city and society that even shared its language.