Caesarian sections (C-sections) were invented in Africa long before Europe, and the rest of the world fully mastered how to conduct them.

The procedure is said to have been started since time immemorial. When a baby could not be delivered vaginally, midwives and surgeons would turn to C-sections in order to deliver the baby safe and alive. In areas around Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria, midwives and surgeons would perform this procedure.

So when a baby could not be delivered vaginally, the midwives and surgeons would sedate the mother in labour with a lot of banana wine. Yes, banana wine. A knife would be sterilized using heat, while the mother would be tied to the bed for her safety. An incision would be made quickly by a team, and the quickness was to ensure that there would be no excessive loss of blood, and also that other organs would not be cut. A conflation of sterilized knives which are sharp and the sedation would make the experience less painful for the mother.

During these times women rarely developed infections because antiseptic tinctures and salves were used to clean the area and stitches were applied. Shock and excessive blood loss were uncommon. However the most reported problem was that it took longer for the mother’s milk to come in. But this would be resolved through friends and relatives who would nurse the baby instead.

Uganda, Tanzania and DRC were the countries where this was most practised; and in Uganda, C sections were normally performed by a team of male healers, but in Tanzania and DRC, they were typically done by female midwives.

It was in the Ugandan kingdom of Bunyoro that this procedure was most documented. The procedure was performed well such that Robert W. Felkin, a Scottish medical anthropologist documented all of this in the book, The Development of Scientific Medicine in the African Kingdom of Bunyoro Kitara.

He witnessed the procedure in 1879 and was captivated by it. What got his attention was that back in Europe, a C-section was considered to be an option only to be used in the most of desperate situations. At this time, “nearly half of European and US women died in childbirth, and nearly 100% of European women died if a C section was performed.”

To him, this was a marvel that needed to be spread to the rest of the world. And that was done.

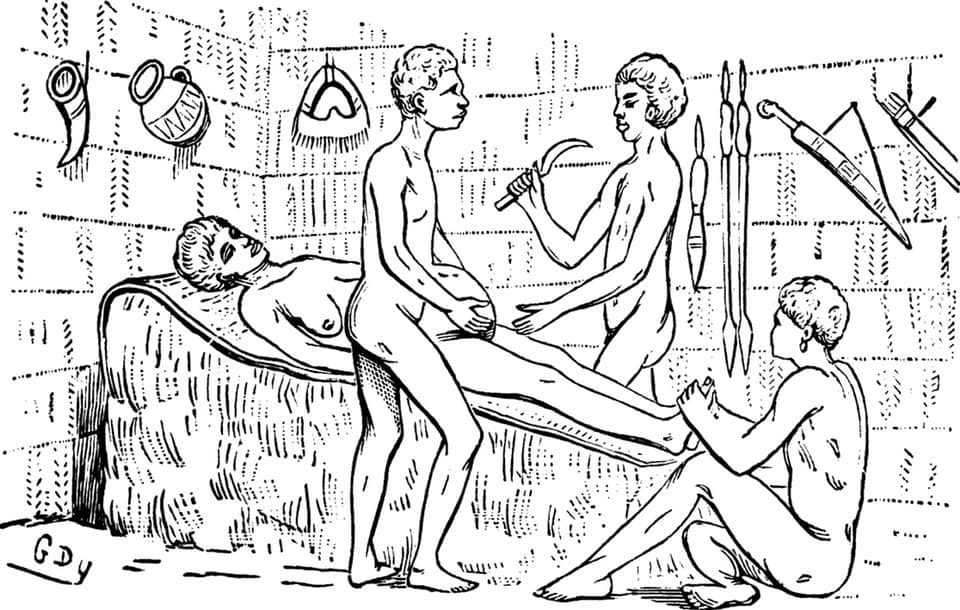

Part of his report read: “A 20-year old woman, carrying her first pregnancy, lay on an inclined bed. She was supplied with banana wine and was in a semi-intoxicated state. She was perfectly naked.

“A band of mbugu (bark-cloth) fastened her chest to the bed, while another mbugu band fastened down her thighs and a man held her ankles. A man standing on her right side steadied her stomach, while the operator stood on the left side holding his knife aloft and muttering an incantation.

“The operator washed his hands and the patient’s abdomen, first with wine and then with water. Then having uttered a shrill cry that was taken by the crowd assembled outside the hut, he proceeded to make a rapid cut in the middle line.“The whole abdominal wall and part of the wall of the uterus (womb) was severed by this incision, and the amniotic fluids (water which surrounds the baby) shot out.

“The bleeding points in the abdominal wall were touched with red-hot iron by an assistant. The operator then swiftly increased the size of the incision in the womb; meantime another assistant held separated abdominal walls with his hand, and proceeded to hold the separated wall of the womb with two of his fingers, but at the same time holding the abdominal wall apart.

“The child was rapidly removed and given to an assistant and the umbilical cord was then cut. The operator put his knife away and seized the contracting womb with both hands giving it a squeeze or two.

“He next put his right hand into the cavity of the womb and using two or three fingers dilated the part of the womb which connects to the vagina from within outwards.

“He then cleaned the uterus and uterine cavity of clots and lastly removed the placenta (afterbirth) which had separated by now.“His assistant was endeavouring but to no avail to prevent the intestine from escaping the incision. The red-hot iron was used once more to stop the bleeding from the abdominal wound, carefully avoiding the healthy tissue.

“The operator then lets loose the womb which he had been pressing the whole time. No sutures were applied to the wall of the womb.“The assistant holding the abdominal walls now let go and a porous grass mat was placed over the wound and secured.

“The mbugu bands were untied and the woman was brought to the end of the bed where two assistants took her in their arms and held her upside down so as to let the fluid in the abdominal cavity drain out onto the floor.

“She was then returned to the original position. The edges of the wound were brought together into close opposition, using seven well-polished iron pins which were fastened by a string made from mbugu.

“A paste prepared by chewing two different roots and spitting the pulp into a bowl was then quickly plastered over the wound and a warmed banana leaf was placed on top of the paste.

“A firm bandage was applied to the wound and dressing using mbugu cloth.

“During the whole operation, the patient never uttered a moan or cry. She was comfortable after the operation. Two hours later she was breastfeeding her newborn.

“On the third day after the operation, the dressing was changed and one pin was pulled out. This procedure was repeated on the fifth day after the operation but this time three pins were removed.

“The rest of the pins were removed six days after the operation. At every dressing new pulp was applied and pus was removed using foam from the same pulp.

“Eleven days after the operation the wound was entirely healed; the patient had no fever and was very comfortable. The secretions from the birth canal were normal.”

It has been said that what Felkin reported in his book is not very much different from what a modern C-section procedure done by modern doctors is like.

Header image credit -Face2face Africa