Over 95% of international data and voice call traffic travels through nearly a million miles of underwater communication cables.

These cables carry government communications, financial transactions, email, video calls and streaming around the world.

The first commercial telecommunication subsea cable was used for telegraphs and was laid across the English Channel between Dover, England and Calais, France in 1850.

The technology then evolved to coaxial cables that carried telephone conversations, and most recently, fiber optics that ferry data and the internet as we know it.

“About ten years ago, we saw the advent of another big category, which is the webscale players and the likes of Meta, Google, Amazon, etc., who represent now probably 50% of the overall market,” said Paul Gabla, chief sales officer at Alcatel Submarine Networks.

Alcatel is the world’s largest subsea cable manufacturer and installer, according to industry trade magazine Submarine Telecoms Forum.

Demand for subsea cables is increasing as tech giants race to develop computation-intensive artificial intelligence models and connect their growing networks of data centers.

Investment into new subsea cable projects is expected to reach around $13 billion between 2025-2027, almost twice the amount that was invested between 2022 and 2024, according to telecommunications data provider firm TeleGeography.

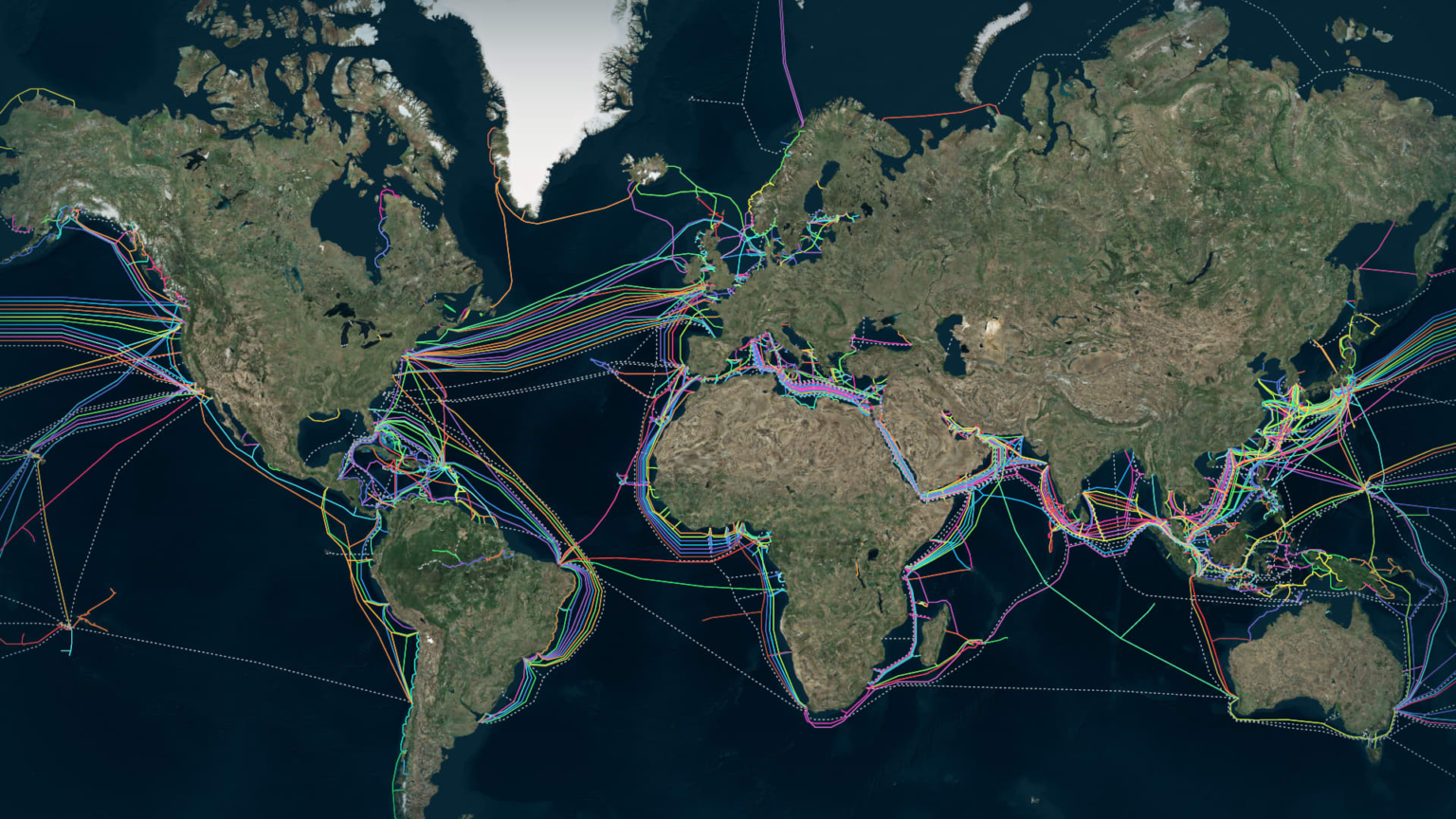

A map of the world’s undersea communication cables.

CNBC | Jason Reginato

Big Tech, big cables

“AI is increasing the need that we have for subsea infrastructure,” said Alex Aime, vice president of network investments at Meta. “Oftentimes when people think about AI, they think about data centers, they think about compute, they think about data. But the reality is, without the connectivity that connects those data centers, what you have are really expensive warehouses.”

In February, the company announced Project Waterworth, a 50,000km (31,000-mile) cable that will connect five continents, making it the world’s longest subsea cable project.

Meta will be the sole owner of Waterworth, which the company says will be a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar project.

Amazon also recently announced its first wholly-owned subsea cable project called Fastnet.

Fastnet will connect Maryland’s eastern shore to County Cork, Ireland, and capacity will exceed 320 terabits per second, which is equivalent to streaming 12.5 million HD movies simultaneously, according to Amazon.

“Subsea is really essential for AWS and for any connectivity internationally across oceans,” Matt Rehder, Amazon Web Services vice president of core networking, told CNBC in an interview about Amazon’s subsea cable investments. “Without subsea you’d have to rely on satellite connectivity, which can work. But satellite has higher latency, higher costs, and you just can’t get enough capacity or throughput to what our customers and the internet in general needs.”

A ship belonging to Alcatel Submarine Networks deploys a plow to install subsea telecommunications cables.

Alcatel Submarine Networks

Google is another large player, having invested in over 30 subsea cables.

One of the company’s latest projects is Sol, which will connect the U.S., Bermuda, the Azores and Spain.

Microsoft has also invested in the infrastructure.

“You’ve seen this huge growth in submarine cables over the past 20 years. And this is driven by just a voracious demand for data,” says Matthew Mooney, director of global issues at cybersecurity firm Recorded Future.

Cut cables

Disruptions due to cable damage can be quite significant, particularly in areas served by few internet connections.

“If you cut a cable, you can cut off multiple countries from internet access, and that includes financial transactions, banking, e-commerce and basic communications,” said Erin Murphy, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a nonprofit national security research organization.

That very thing happened to Tonga, an island nation east of Australia.

In 2022, debris from an underwater volcanic eruption severed the island’s only subsea communication cable, cutting the island off from the rest of the world.

In September, cuts to subsea cables in the Red Sea caused disruptions to Microsoft’s Azure cloud service. The company was able to re-route traffic, but users in Asia and the Middle East still faced increased latency problems and degraded performance.

Experts have said that the majority of subsea cable damage is accidental, usually due to fishing activity or a ship accidentally dropping its anchor on a cable. But lately, these cables are becoming the suspected targets of sabotage.

A subsea cable being manufactured at Alcatel Submarine Networks factory in Calais, France.

CNBC

“When you have so many vessels in international waters that are highly trafficked by lots of commercial vessels or fishing vessels, the likelihood of accidents is fairly high,” Murphy said. “But if you’re a hostile actor, you know that as well. So if you’re sending out the so-called Russian ghost fleet, or if you have a Chinese fishing vessel and a cable is accidentally cut, you could just say, ‘Oh, well, it was an accident.’ But it could be intentional. So it’s really hard to discern sometimes when an act of damage is actually intentional or accidental.”

Mooney and Recorded Future have been tracking some of these cases of suspected sabotage.

“I would say that we have seen a significant uptick in what we would consider intentional damages,” Mooney said. “In 2024 and 2025, [we] saw a notable increase in incidents that occurred in the Baltic Sea and around Taiwan. And so it is difficult to be able to determine with 100% validity that these are intentional. However, the fact patterns that emerge from these events does give you cause to be suspicious that they could all be considered accidental.”

Mooney said the increase in suspected sabotage has corresponded to increased tensions between Russia and Ukraine and China and Taiwan.

Despite there being a lack of concrete evidence of subsea cable sabotage, governments are taking the threat seriously.

In January, NATO launched the “Baltic Sentry” following several incidents of cable cuts in the Baltic Sea. The operation involves deploying drones, aircraft and subsea and surface vessels to safeguard the subsea infrastructure in the region.

“As a result, I don’t believe we’ve seen any instances of cable severing since late January 2025, in the Baltic Sea,” Mooney said.

A picture taken on February 4, 2025 shows a Helicopter 15 (HKP15) (L) on the flight deck of patrol ship HMS Carlskrona (P04) on open water near Karlskrona, Sweden, as part of the NATO Baltic Sea patrol mission, the Baltic Sentry, aimed to secure critical underwater infrastructure. The patrol ship HMS Carlskrona (P04) set off from the naval port in Karlskrona on February 4, 2025 to become part of NATO’s Baltic Sentry operation as one of several Swedish ships that are part of Standing NATO Maritime Group One (SNMG1). This is the first time the ship has hoisted the NATO flag on board. The purpose of NATO’s Baltic Sentry operation is to demonstrate presence and secure critical underwater infrastructure. (Photo by Johan NILSSON / TT NEWS AGENCY / AFP) / Sweden OUT (Photo by JOHAN NILSSON/TT NEWS AGENCY/AFP via Getty Images)

Johan Nilsson | Afp | Getty Images

U.S.-China tension

In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission, which is responsible for granting licenses to anyone wishing to install or operate subsea cables connecting to the U.S., has introduced tighter rules on foreign firms building this infrastructure, citing security concerns.

“One area we’ve been particularly focused on are threats that come from the Chinese Communist Party as well as from Russia,” FCC Chair Brendan Carr told CNBC. “So we’re taking actions right now to make it difficult or effectively prohibiting the ability to connect undersea cables directly from the U.S. to a foreign adversary nation.”

Carr said the FCC is also taking steps to make sure the hardware itself isn’t compromised, not allowing Huawei, ZTE or other questionable “spy gear” to be used in undersea cables.

In July, three House Republicans sent a letter to the CEOs of Meta, Amazon, Google and Microsoft asking if the companies have used PRC-affiliated cable maintenance providers.

In response to CNBC’s question about the letter, Meta’s Aime said, “We do not work with any Chinese providers of cable systems on systems that we’ve announced, and we are in full compliance with U.S. policy regulations around partners in the ecosystem and the supply chain.”

Amazon also told CNBC it does not work with Chinese companies.

Microsoft and Google did not return CNBC’s request for comment on the letter.

To understand how subsea cables work, CNBC visited Alcatel Submarine Networks subsea cable manufacturing facilities in Calais, France and Greenwich, England. We also spoke to government officials and tech giants to find out why subsea cables are crucial to keeping us connected and what we can do to protect this critical infrastructure.

Watch the video to get the full story.

https://www.cnbc.com/2025/11/08/big-tech-ai-underwater-cables.html