Brad Setser is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations

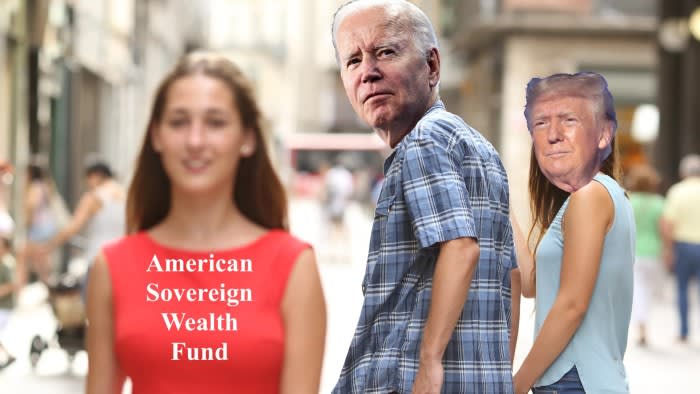

Everyone seems to want a sovereign wealth fund these days. Even countries that have more sovereign debt than sovereign wealth are hot on the idea.

It’s a hot topic. Over time, less and less of the growth of the foreign assets of the world’s governments has taken the form of traditional FX reserves, and more and more has taken the form of swelling sovereign wealth funds (see the chart below).

However, the SWF term has gotten stretched to the point where it has almost lost meaning. So here’s a short(ish) taxonomy of the different funds, what they do and where their money comes from, before turning to the suggestion that the UK and US should get their own SWFs.

The OG SWFs

The original sovereign wealth funds were basically mechanisms for investing excess foreign exchange reserves abroad in equities and other assets that were too volatile or illiquid for traditional foreign exchange reserve managers.

The bulk were set up by countries with huge oil revenues. The proceeds were initially simply parked at the central bank and basically managed as foreign exchange reserves — ie in safe fixed income like Treasuries and other high-grade debt.

That’s how Saudi Arabia long managed the more transparent portion of its oil wealth — the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority reported large deposits from the rest of the government that offset its large reserves — and how Russia generally managed its oil surplus.

But Abu Dhabi — the most oil-rich of the United Arab Emirates — Kuwait, and Qatar all set up “investment authorities” (ADIA, KIA, and QIA) to invest in equities, not just traditional reserve assets. Over time they started to invest in hedge funds and private equity, and became very big.

Norges Bank Investment Management, also fits this model. Norway found oil and gas after it was already fairly rich, and decided to channel almost all its energy income into an endowment managed by Norges Bank (this sovereign wealth fund is in effect a subdivision of the central bank). However, NBIM diverges from other similar hydrocarbon SWFs in its transparency, strict rules and avoidance of high-fee fund managers. It is in practice a giant index fund.

Singapore doesn’t have a lot of oil but it does intervene heavily in the foreign exchange market. That has allowed it to set up the Government Investment Corporation (GIC) with its excess foreign exchange reserves. Think of the Yale endowment model of investment, but for a country. The GIC now has so much money that it won’t disclose the amount.

Singapore continues to intervene so heavily in the foreign exchange market that it has transferred another $200bn to the GIC over the past few years, albeit with a bit more transparency than in the past.

There’s also a smattering of other smaller, resource-funded sovereign wealth funds, such as the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan/SOFAZ (which isn’t really a pure sovereign wealth fund, given its domestic activity) and Botswana’s Pula Fund, where the assets come from diamond rather than energy sales.

All told, “traditional” sovereign wealth funds likely have over $3tn in external assets, which is pretty significant relative to the world’s $12tn in traditional reserve assets.

SWFs with Chinese characteristics

China’s formal sovereign wealth fund, the China Investment Corporation (CIC), broadly follows the classic model. But the CIC is a SWF with many Chinese characteristics.

It was financed out of funds that were bought from the central bank using yuan, raised through a special bond issue that was bought by the state banks. Most of its external assets (reported to be around $318bn; see the “Financial assets at fair value through profit or loss” line on page 91 of its 2022 annual report) are invested in foreign equities and alternatives (it has a ton of private equity, see the reporting of MainFT itself).

But at times, it has dabbled in investments that support Xi Jinping’s policy objectives — for example, the Hong Kong-based Guoxin International Investment Co, which supports resource investment abroad. It’ also rumoured to have dabbled in supporting the domestic equity market at times as a part of the “national team” (it certainly can buy bank stocks).

Most importantly, the CIC bought (from China’s reserve manager) the stakes in the state banks that the People’s Bank of China received when its reserves were used as the “currency” of the initial recapitalisation of four of the big five state commercial banks. This, in fact, accounts for the majority of the CIC’s initial $200bn in seed capital. Those stakes are held by an entity that is fully controlled by the CIC — Central Huijin Investment — and now account for the bulk of its reported assets.

CIC is therefore probably best thought of as a bank holding company with a small traditional sovereign wealth attached to it. In fact, the CIC now also owns the “bad banks” that were set up to move the bad assets off state banks’ balance sheets prior to their recapitalisation with foreign exchange reserves. Red capitalism is full of ironies.

Amateurs often make the mistake of subtracting the CIC’s total reported assets — which include the $860bn (as of end 2022) stake in the state banks — from China’s reported reserves. That’s the wrong way to do the balance of payments maths. The right way is to add the CIC’s external assets to the State Administrator of Foreign Exchange’s reported reserves.

To make things more confusing, SAFE, China’s traditional reserve manager also invests a portion of its $3.2tn of foreign exchange in both equities and “alternatives”. As a result, some refer to its Hong Kong subsidiary, SAFE Investment Company Limited, as a sovereign wealth fund.

However, SAFE has used its reserves to recapitalise the policy banks (the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank) and thus created an entity — Buttonwood Investment — to manage that stake. It has also used reserves to capitalise some smaller Chinese SWFs that support the Belt and Road (The Silk Road Fund, the China-Africa Development Fund, the China-LAC Cooperation Fund, etc.).

Basically, China is so big, and the state so sprawling, that it ended up with multiple sovereign funds, almost all with Chinese characteristics.

Pensioner SWFs

There’s another type of sovereign wealth fund that has some of the attributes of a traditional one but typically isn’t funded out of reserve assets: sovereign pension funds.

Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), which reports to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, is the best example, followed closely by the Korean National Pension Service (NPS) which reports to the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Some include the North American subnational state pensions funds and Australia’s superannuation funds in this category, but they are typically one step removed from state government, and they have clear offsetting liabilities and thus don’t have a large net worth.

These sovereign pension funds typically start by taking pension contributions and investing them in domestic assets. Think of the US payroll taxes that were invested in the Social Security Trust Fund (which itself only bought government bonds).

But at some point, the big government pension funds have started to invest in external assets — typically bread and butter foreign equity indices and foreign bond funds rather than the real estate and trophy assets bought by the Gulf.

The numbers are big, given their size and the large international allocations. About 50 per cent of GPIF’s assets are invested abroad, and Korea aims to bring the foreign allocation of the rapidly growing NPS to 60 per cent. That means the foreign portfolio of the GPIF is about $750bn, and the foreign portfolio of the NPS now tops $400bn.

These funds are interesting because they can have a large impact on the foreign exchange market. For example, a few years ago the Bank of Korea’s governor Rhee Chang-yong (correctly) worried that the steady outflow from the NPS was undermining the Bank of Korea’s effort to prop up the won back in the summer of 2022, and responded with an innovative swap facility. The Koreans now are taking additional steps to minimise the market impact of the $2-3bn a month in foreign exchange the NPS typically buys.

Strategic wealth funds

There’s a final type of fund, one that is becoming increasingly common — you might call them strategic wealth funds, domestic development funds, public investment funds or perhaps even national development banks.

These “sovereign wealth funds” primarily manage the state’s domestic investments and typically invest in projects judged to be strategic for a country’s development plans (eg the “Saudi Vision 2030”).

One example is Singapore’s Temasek, which was set up to manage Singapore’s state-owned enterprises (for example, Singapore Airlines). However, lines get blurred: Singapore didn’t need to use the proceeds of the privatisation of many state firms to support its budget, so Temasek started investing abroad, just like a traditional sovereign wealth fund.

The Saudi Public Investment Fund is another good example. The PIF got its initial funding from Saudi Arabia’s foreign exchange reserves (it has received at least $40bn), but later on it received the proceeds from listing Saudi Aramco and money from PIF’s own external borrowing. The PIF’s 12 per cent stake in Saudi Aramco also gives it a new means of raising more funds for investment, but selling its stake would mean trading future income for cash now.

The PIF famously has taken some big risks abroad — sometimes in companies that agree to invest in Saudi Arabia in return for a PIF investment, and sometimes in companies that the Saudis want to court for other reasons (Jared Kushner’s fund for example).

But PIF also invests heavily in purely domestic projects, particularly those that have the personal backing of Mohammed bin Salman and play a part in the Saudi 2030 Vision. MainFT has done some very good reporting here as well — notably highlighting how the PIF is pushing into sectors traditionally controlled by Saudi business families, as MBS considers state capitalism a means of modernising Saudi business culture.

The United Arab Emirates has its share of sovereign wealth funds in this tradition as well — Mubadala, the Royal Group (which controls IHC), ADQ (which is building a new city in Egypt), the Investment Corporation of Dubai and the like. Many of these funds blur the line between domestic and foreign investment.

The Turkey Wealth Fund (TVF) received the government’s stake in number of domestic companies (the state banks, Turkcell etc) and calls itself an “asset-backed” development fund. It raised some more funds when it sold 10 per cent of the Istanbul Stock Exchange to the QIA in 2020, and a dollar bond earlier this year, leading to quips that it is Turkey’s sovereign debt fund.

Ethiopia’s sovereign wealth fund is similar. As its name implies, the Ethiopia Investment Holdings serves as the holding vehicle for a lot of state assets — Ethiopian Airlines, a big local bank, local sugar refiners and an apparently profitable spirits distillery. It also aspires to be a conduit for Gulf funds looking to invest across the Red Sea.

Anglo “wealth” funds?

These models don’t really work for the US or the UK, however. The US doesn’t have a tradition of public ownership, and the UK sold its national champions a long time ago. Both have twin budget and current account deficits, so there are no surplus to stash away either.

The US could potentially sell off the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to fund a sovereign fund, but that goes against the Biden Administration’s (correct, IMO) recognition that the salt caverns are in fact a critical strategic asset. There are substantial economic (and financial) returns from the ability of the US to use its immense storage capacity to buy low and sell high and stabilise such a crucial market.

Of course, both the US and UK could sell a bit of debt to fund strategic investment funds. After all, not all public investment funds originate out of foreign exchange reserves. If the returns are greater than the cost of borrowing it can make sense, at least in theory.

Indeed, the most relevant model may come from a country that prides itself on its distinction from “les Anglo-Saxons.”

France runs persistent budget and current account deficits but still has a long-established de facto sovereign wealth fund, the Caisse des dépôts et consignations. And the French government has a tradition of investing in strategic sectors. Indeed, the history of France’s climate-critical nuclear sector shows that state-backed engineering projects can succeed even in a democracy (though there are obviously also plenty of cautionary tales).

At least in the US, the creation of a strategic public investment fund shouldn’t be ruled out. In many respects, having some kind of vehicle like this makes sense. In fact, it might even have been helpful in the past.

For example, it wouldn’t have been crazy for the US to have gotten some warrants in return for the $465mn 2010 loan that helped Tesla finance its initial transition from making a few sports cars into manufacturing sedans (the model S). The loan was repaid early in 2013, but the US government didn’t get to benefit from Tesla’s IPO, or its ca 380x growth in market value since then (which could in theory alone have capitalised a US SWF).

These days the US government provides lots of direct grants and loan guarantees (for example, to support domestic semiconductor investments), but it doesn’t have a tradition of getting potentially valuable upside exposure in exchange. The US did get warrants for its investments in the big US banks through the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP), which generally proved valuable. It should probably do so more often, especially if it more openly embraces a more active industrial policy.

However, a clean and robust governance structure will obviously be essential for any state fund designed to invest in strategic domestic sectors. The temptations for misuse are enormous. The classic SWFs generally originated in autocracies, and any British or American ones shouldn’t be reliant on a benign king or queen.

https://www.ft.com/content/a65135e9-1fde-4aee-a422-b0d783c62e14