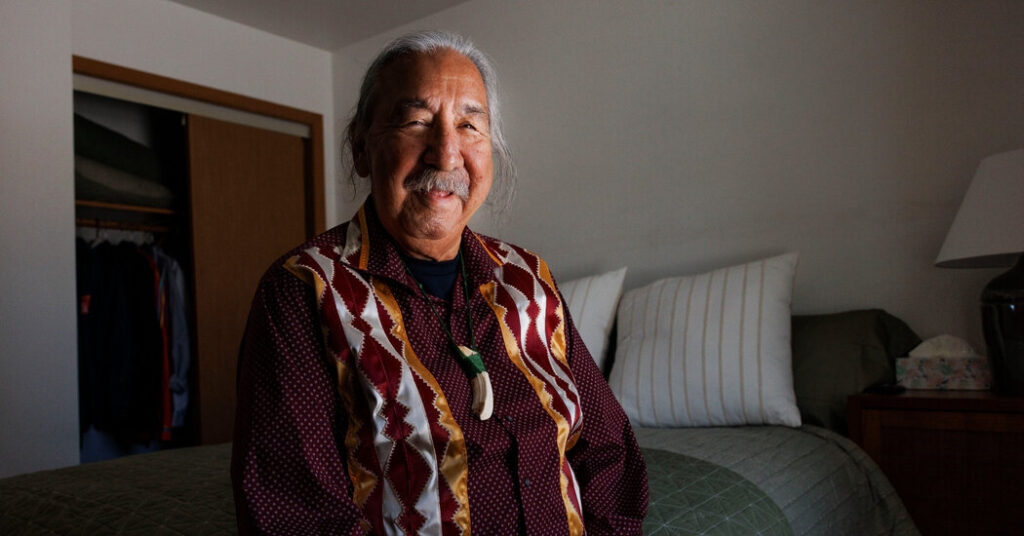

Leonard Peltier had waited five decades to do something he had increasingly doubted he would ever be able to: say thank you, in person, to the fellow Native Americans and others who had spent those years fighting for his freedom.

Addressing a raucous crowd of 300 supporters on his home reservation on Wednesday, Mr. Peltier, now 80, pumped his right fist repeatedly and displayed remarkable stamina for a partly blind man who needs a walker. A day earlier, he had been released from a federal prison in Central Florida, where he had been serving two life sentences for the killing of two federal agents.

Now he was back with his people, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, in North Dakota. There he will be allowed to serve the remainder of his sentence under house arrest after President Joseph R. Biden Jr. issued a clemency order in one of his final acts before leaving office.

“I’m proud of the position I’ve taken — to fight for our rights to survival,” Mr. Peltier said during an eight-minute speech in which he expressed gratitude, but also defiance. “I’m so proud of the support you’re showing me, I’m having a hard time keeping myself from crying,” he said. “From the first hour I was arrested, Indian people came to my rescue, and they’ve been behind me ever since. It was worth it to me to be able to sacrifice for you.”

It was a moment that seemed highly unlikely as recently as July, when Mr. Peltier was denied parole yet again in connection with the deaths of two F.B.I. agents during a shootout on a reservation in South Dakota in 1975.

To many law enforcement officials, Mr. Peltier is a remorseless killer whose appeals had been reviewed, and rejected, by more than 20 federal judges.

But to human rights groups such as Amnesty International, as well as to supporters who included the Dalai Lama, the former South African president and anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela and the musician Steven Van Zandt, Mr. Peltier had become a cause célèbre who had been wrongfully convicted as part of a history of Native American repression.

“Friends, relatives, strangers ached for Leonard, prayed for him, danced for him, fasted and suffered for him, cared for him, longed for him to walk the earth as a free man,” Louise Erdrich, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist who is also a member of the Turtle Mountain tribe, said in an email.

Ms. Erdrich attended Mr. Peltier’s trial in 1977, and has long contended that he had unfairly paid the price for the violent actions of other Native American activists.

“Leonard has been a living reproach to the idea of our greatness as a nation,” said Ms. Erdrich, who has saved her correspondence with Mr. Peltier and plans to visit him soon. “We confuse greatness with economic power or military might, but no. Greatness is justice, greatness is tolerance.”

Mr. Peltier was a member of the American Indian Movement, or AIM, an advocacy organization founded in 1968 that promoted civil rights, spoke out against police brutality and other abuses and sought to highlight the federal government’s history of violating treaties it had made with Native American tribes.

In the 1970s, militant members of the group clashed with federal authorities on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. They forcibly seized control of the Sioux village of Wounded Knee and fended off the authorities for 71 days.

Two years after the Wounded Knee standoff, with the relationship between Native American activists and federal law enforcement agencies still frayed, two F.B.I. agents — Jack Coler and Ronald Williams — tried to arrest a robbery suspect on the Pine Ridge reservation.

A shootout ensued, leaving the two agents and one activist dead. Mr. Peltier has admitted to firing his gun from a distance but has insisted that he acted in self-defense and was not the one who killed the agents. Of the more than 30 people who were present during the shootout, Mr. Peltier was the only one convicted.

Exculpatory evidence that had helped to acquit two other AIM members accused in the killings was excluded from Mr. Peltier’s trial — an issue that has frequently been raised by his supporters as an example of injustice.

But in a letter in June 2024 opposing Mr. Peltier’s parole application, Christopher A. Wray, then the F.B.I. director, noted that Mr. Peltier had repeatedly lost in court on several issues, such as his attempts to downplay ballistics evidence tying him to the killings.

The order freeing him to return to North Dakota met the vehement objections of many law enforcement officials.

“Peltier gets to go home — while neither Coler or Williams was afforded the same opportunity,” Michael J. Clark, president of the Society of Former Special Agents of the F.B.I., said in an email on Wednesday. “Peltier is a remorseless murderer and should have served out his life sentence in a federal prison.”

Mr. Peltier made it home to the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation late Tuesday, as the sun was fading and temperatures were a dangerously cold minus 15 degrees — a 90-degree swing from the temperature at the most recent federal correctional facility where he had been held, in Coleman, Fla.

Dozens of residents greeted him with signs that read “50 Years of Resistance” as he was whisked to his new home in the town of Belcourt. The house was purchased by NDN Collective, an Indigenous rights group based in Rapid City, S.D., whose leaders greeted Mr. Peltier when he walked out of prison in Florida and accompanied him on a private plane ride back home, according to Nick Tilsen, the group’s founder and chief executive officer.

At a homecoming lunch on Wednesday, as Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” played, banners and signs abounded. Some had clearly been used in previous protests — “Enough Is Enough: Free Leonard Peltier” — but there were also new ones, including a photo of Mr. Peltier with his Bureau of Prisons number, 89637-132, crossed out.

In his remarks, Mr. Peltier talked about how proud he was to call attention to Native issues, and described harsh conditions in prison, including being placed in sensory deprivation cells at some points.

Even in his new circumstances under house arrest, he said, he will have to deal with many restrictions. “But it’s a lot better than being in a cell,” he added.

He then held court for more than an hour, like a Hall of Famer at an autograph signing, as more than 100 people lined up to say hello, present gifts, pose for photos or get something signed.

Some supporters cautioned that he would encounter a different world — some things better, some things worse — than the one he last experienced 50 years ago.

State Representative Jayme Davis, a Democrat from the area who is also a member of the Turtle Mountain tribe, noted that many people had lost their jobs, and that there was deep anxiety about the future.

“Our people are facing immense challenges, especially as our state government moves forward with policies that make survival even harder,” said Ms. Davis, whose father attended school in Belcourt with Mr. Peltier. “But in the darkness of this moment, his homecoming, I feel, will be a beacon of light. His return carries a profound weight, almost as if there’s a message in the timing.”

Mr. Tilsen said that Mr. Peltier had expressed a desire to work on the issue of teenage suicides, having done some volunteer work as a young man on the Pine Ridge reservation. But he also said that Mr. Peltier — who has declined interview requests for the time being — would need some space.

“I think that everybody focuses on him being this iconic international human rights activist and leader, which he is,” he said. “But he’s also been institutionalized for 49 years. So he has to build a new normal.”

Kirsten Noyes contributed research.