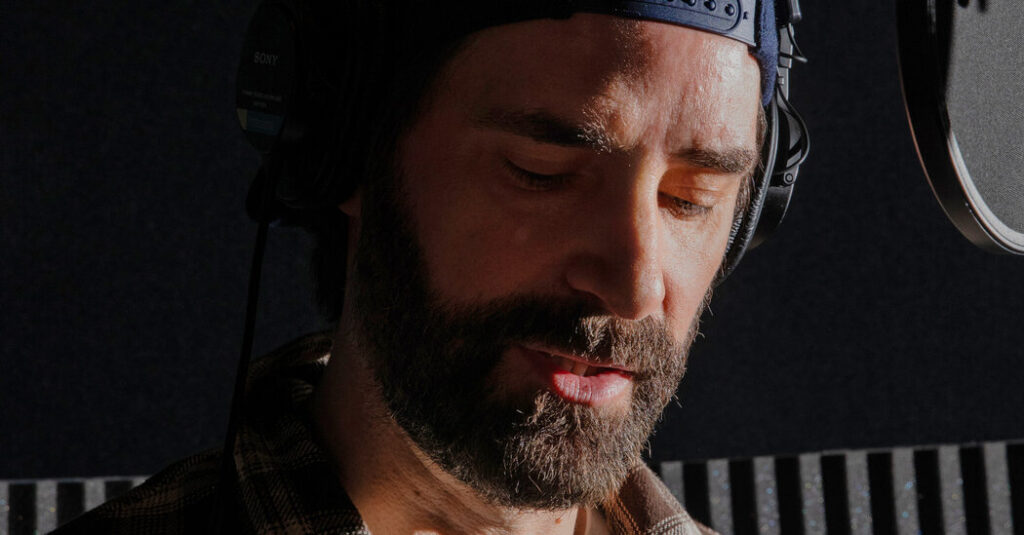

Phil Hanley stood in a womb-like studio, psyching himself up to record the final section of his memoir. Peppermint tea, check. Hands in meditation position, check. Sheaf of highlighted, color coded pages printed in extra large type, check.

But when Hanley leaned into the microphone to read from “Spellbound,” his candid account of growing up dyslexic, he sounded more like an anxious student than the seasoned comedian he is.

He eked out 13 words, then stumbled, exhaling sharply in triplicate, Lamaze style. He tried again, the same sentence with slightly different intonation. Puff, puff, puff. And again, making it through three more words. Puff, puff, puff. On his fourth attempt, Hanley choked up.

It was his 60th hour in the booth at his publisher’s office, not counting practice sessions at home. Most authors are at the studio for a fraction of this time; the average recording length for a 7.5 hour audiobook is 15 hours. But because Hanley has severe dyslexia, the process was protracted. And complicated. And emotional.

“The most traumatic moments of my life have been having to read out loud,” Hanley said. “I can’t even express how tiring it is to do the audiobook. It feels like chiseling a marble statue with a screwdriver and a broken hammer.”

Nevertheless, he was hellbent on reading his own story. What would it say to the dyslexic community if he handed off the mic?

Hanley was an unlikely candidate to write a book in the first place. He has a solid career as a comedian, with a special on Comedy Central, regular appearances at the Comedy Cellar and cameos on “The Tonight Show” and “Late Night with Seth Meyers.” But he’s not a huge reader.

Once in a while he’ll work his way through a novel — “The Road,” by Cormac McCarthy, or anything by Charles Bukowski — but, for the most part, books remind him of school. And for Hanley, who grew up in Oshawa, Canada in the 1980s, that’s where the trouble started.

“Kindergarten was great, but first grade was earth-shattering from the very first day,” he said. “I’d wake up every morning and think, ‘Oh NO.’”

While classmates learned to write, read and spell, Hanley drew lines and shapes that never quite made sense to himself or anyone else. He couldn’t sound out words, couldn’t match a letter with a sound. Letters were a chaotic jumble; a block of text might as well have been an abstract painting. Hanley’s teacher announced the creation of a special one-student spelling group, “because Philip can’t keep up.” She also shouted, “Philip, you can’t do anything right!”

Hanley only made it to second grade because his mother, a former teacher, insisted. He still didn’t know how to read, and he wouldn’t learn for a long time.

Thus commenced a decade of shame, humiliation and running out the clock on his own schooling. When Hanley was diagnosed with severe dyslexia at age 10, there was no customized curriculum or individualized learning plan. He was placed in a special education classroom alongside students whose myriad needs were addressed with a “one size fits all” approach. He spent one semester memorizing Christmas carols, another weaving a single place mat. He entertained himself — and others — by cracking jokes.

Hanley remembers this period in black and white, with color flowing in around summer vacations. His mother hid back-to-school circulars because she knew they would upset him. She volunteered at the school library to make sure he was receiving fair treatment.

But his family’s unflagging support could only carry him so far.

“I was told that I was dumb and lazy my whole life,” Hanley said. Then he started to cry.

He cried nine times over the course of an interview. He was also witty, self-deprecating and evangelical about the Grateful Dead. (Bob Weir is dyslexic, “and he owns it.”)

After graduating from high school — winning Most Improved Student because he finally had one-on-one help and the extra time he needed for exams — Hanley headed to Milan and London to model. His childhood friend, Shalom Harlow, had paved the way; he figured he could skate by without reading, although addresses and directions were challenging. Hanley posed for Dolce & Gabbana and Armani before returning to Vancouver, where his parents had moved.

Reeling from a breakup, and beginning to reckon with what he describes in the book as “body-quaking anxiety,” Hanley turned to comedy. First he took a class. Then he performed during improv night at a bar. He worked on a sketch with a friend. He hatched funny scenes for another friend who worked on the Air Bud movie franchise (think talking dogs).

Slowly, with stops at several outposts of Canada’s Yuk Yuk’s Comedy Club, Hanley made his way to the Comedy Cellar in Manhattan’s West Village, where dyslexia became go-to material.

“With standup, you examine anything that’s different about you,” Hanley said. “You take a terrible experience and you get something out of it. You make people laugh.”

When a literary agent broached the subject of a memoir, it was Hanley’s turn to laugh. He thought the idea sounded “insane,” like the worst “Shark Tank” pitch ever. His war with words hadn’t ended at graduation: He still struggles to read a menu, address an envelope and make sense of names he hasn’t memorized.

“Fundamental things that make functioning as a human easy, I lack those,” he said.

But Hanley was haunted by the questions he’d fielded once, at an event hosted by a nonprofit that supports neurodiverse students. After his set, several young people asked, in effect, how are you not ashamed of being dyslexic?

“Do you feel shame if you’re diabetic or have epilepsy?” Hanley said. “We have these challenges in life, but on top of that you’re going to feel shame?”

Hanley has come to think of dyslexia as a gift, one that spurred him to be creative and quick on his feet, to solve problems and connect with people. He even credits dyslexia for his move to New York City, where he finds the numbered streets easier to navigate.

Of course, it’s also ripe for comedy.

“I arrived in first grade, everyone started reading,” Hanley said on “The Tonight Show.” “I was like, ‘Meh, I’m gonna stare out the window for a decade. But you guys, you do your thing.”

He went on, “Tell a dyslexic child to sound it out? That’d be like if someone pulled you aside and said, ‘Hey, I can’t eat this, I’m deathly allergic to peanuts,’ and you’re like, ‘Chew slowly.’”

“Spellbound” took eight years to complete. Hanley started the proposal while staying in Amy Schumer’s apartment after another breakup. He made lists of people and places he remembered, watched YouTube videos on active writing and hired a freelance editor who gave him a crash course on punctuation. He committed to concise sentences — easier for dyslexic readers — and labored over the first chapter four months. Eventually he was able to write one in two weeks.

“It was cathartic,” Hanley said. “It was hard. But I’m used to things being hard.”

His team — agent, manager, editor at Holt — advised him that he could outsource the audiobook to a professional narrator. “It felt contrary to my whole point,” he said. “If the message is, you try really hard and you can do this thing, and then I’m like, ‘Oh, but I couldn’t do the audiobook?’”

The recording happened over 16 sessions of roughly four hours each.

“At first, it would almost be like holding my breath underwater,” Hanley said. “I would be in this praying position: You can do this.”

Guy Oldfield, who produced and directed the audiobook, said, “I knew Phil could do it because I’ve seen him do stand up. The challenge was, suddenly there was no audience: It was just Phil and the text.”

Oldfield and his colleagues at Macmillan Audio might not have been able to gin up the energy of a packed house, but they made Hanley feel heard, and safe.

Before each appointment, Sal Barone, the engineer and editor of the project, printed out a 50-page section of “Spellbound” in 20-point, dyslexic-friendly font. (At this size, the 257-page book ballooned to around 800 pages.) The packet was hand-delivered to Hanley’s apartment in the East Village. If Hanley was away — he was on the road for six weekends in a row — a member of the team deposited the packet at the Thai restaurant on the ground floor of his building.

Hanley took it from there. He highlighted quotes in yellow and punctuation in pink, so he knew when to take a breath. Using his air fryer as a podium for balancing pages, he practiced reading — memorizing, really — and doing accents for several hours.

On recording days, Hanley would order an egg and cheese bagel at his favorite deli, then eat it in a taxi en route to the studio. (He’d ask for permission, of course: “I’m still Canadian.”) Then, a cup of tea upon arrival and into the darkness he went.

Behind the microphone, Hanley was reminiscent of shaken-up bottle of soda — fizzy with pressure and words that didn’t always pour in an orderly fashion.

“There were moments early on where he couldn’t get a particular word,” Oldfield said. “He just could not say it.”

Barone said, “It seems counterintuitive, but taking a break wasn’t always the best option. We’d keep going, and return to the problematic part later.”

Oldfield encouraged Hanley to emphasize certain lines and words. He introduced the “schwa” sound, which smoothed Hanley’s over pronunciation of individual syllables. The concept was appealing to Hanley, whose hometown, Oshawa, is known as “The Shwa.”

“Phil just wanted to work without judgment,” Oldfield said. “He was severely judged as a child. We created an environment for him where he was not judged, and he delivered.”

On his final full session in the booth, the sentence Hanley kept stumbling on was about his mother. It read, “We have a bond that only two people who have been through something as a team and triumphed can share.”

Joan Hanley still remembers the feedback she received from her son’s teachers 40 years ago — that he was lazy, wasn’t trying hard enough and depended too much on her.

“He was doing his best,” Joan, 83, said in an interview. “It wasn’t his fault that he was learning differently. He was smart and artistic. He always had friends. We were always proud of him. We still are.”

For Hanley, that support made all the difference. He said, smiling, “I’ve never bombed with my mom.”

He hopes parents will hear this message in his book, which came out this week: “The qualities that you want to instill, you’ll have those by the end of first grade if your kid is dyslexic,” he said. “They’ll have character, tenacity, determination. They’ll have the grit of someone who’s been through two divorces.”

As if delivering his favorite punchline, Hanley added, “Just maintain their self esteem.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/19/books/spellbound-phil-hanley.html