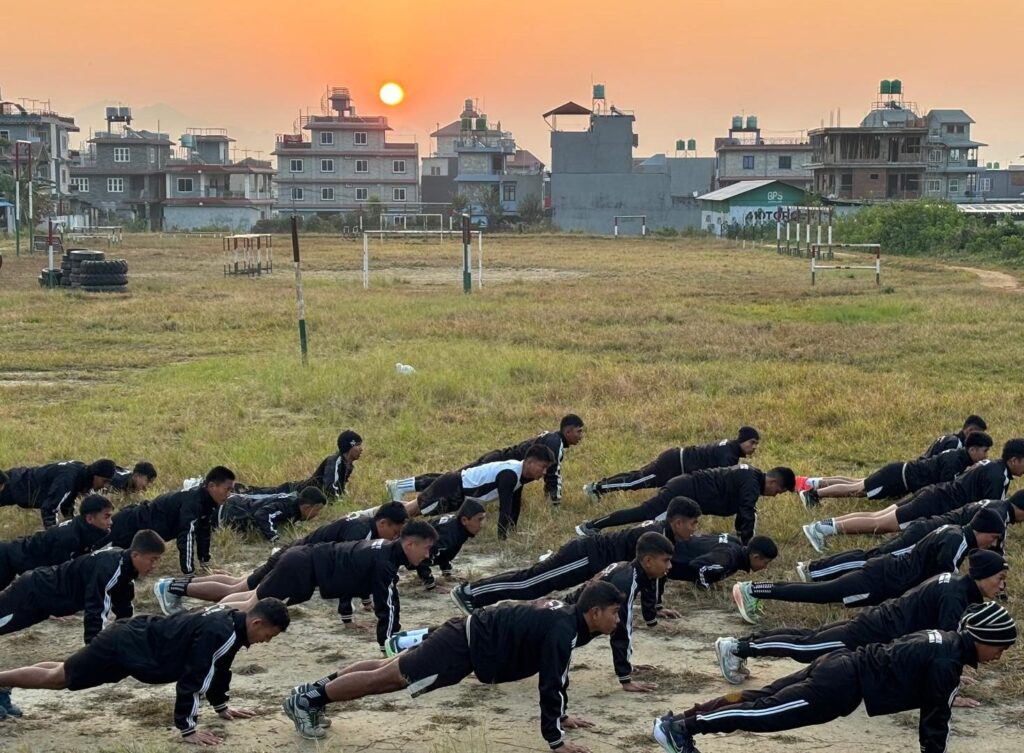

Pokhara, Nepal – The rhythmic thumping sound of about 60 young men doing jumping jacks to warm up fills the chilly late November air at a picturesque playground in Pokhara, a city in western Nepal.

The teenagers’ instructor is training them for the next round of the Gurkha recruitment programme which will admit them into the British Army or the Singapore Police Force.

Shishir Bhattari, 19, who hails from a town in central Nepal, is among the young men training at the ground owned by the Salute Gorkha Training Center.

“I’ve wanted to be a part of any army in the world since I was a child,” he tells Al Jazeera. “The credit for this dream goes to my mother who always encouraged me.

“When I was in the sixth grade a member of the British Army came to our school to give us a talk about how they function. I was impressed by their ‘free, fair and transparent’ selection process, making me aim to join the British Army.”

“Before training for the British Army, I had a dream to join the Indian Army. So many of the Gurkhas [soldiers primarily native to Nepal] have served in India and I’m also keen to uphold the legacy of our ancestors. I also loved the Bollywood movie Shershaah whose storyline is about the Indian Army and that motivated me even more,” he says.

But young men like Shishir no longer have the option of joining the Indian Army after Nepal’s government suspended that Gurkha recruitment pipeline in protest over changes in New Delhi’s hiring rules in 2022.

“It’s quite sad,” he says. “In the past if we didn’t get into the British Army or Singapore police, we at least had the option of trying out for the Indian Army. I hope India changes the rules. It will help many of us and give us more work options.”

‘World’s fiercest fighters’

Gurkhas, renowned for being among the world’s fiercest fighters, have been a formal part of the Indian Army for decades and have also fought for the country in key battles such as the country’s Kargil War in 1999 against armed groups from Pakistan.

Their presence in India goes back to the early 1800s when the subcontinent was under British rule. Back then, they were recruited by the British East India Company. Post-independence a tripartite agreement between India, the United Kingdom and Nepal was signed, allowing New Delhi to continue recruiting Gurkhas into the Indian Army.

But this recruitment agreement came to a standstill in 2022 when India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi changed the rules of the country’s armed forces’ recruitment scheme.

A new system, called “Agnipath”, which means “path of fire” in Hindi, was introduced in June 2022. Under this system, men and women between the ages of 17 and a half and 21 years old, are recruited for a fixed four-year tenure only. At the end of their tenure, only about a quarter of them – the best – are to be hired for regular service. The remaining cadets will have to leave and will not receive any pension.

Previously, Gurkhas have served for much longer – 10 to 17 years on average – in the Indian Army. In August 2022, Kathmandu paused Gurkha recruitment to the Indian Army. The government led by the then-prime minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal (now leader of the opposition) said that the tripartite treaty, which requires that Nepal be consulted about changes to the army hiring scheme, had not been upheld.

Retired honorary captain Krishna Bahadur, who served as a Gurkha in the Indian Army for about 30 years, and is currently the chief instructor at the Salute Gorkha Training Center, describes India’s Agnipath scheme as “all politics”.

“It has seriously impacted the employment prospects for young boys in Nepal,” Bahadur tells Al Jazeera. Without the option of joining the Indian Army, many will “end up unemployed”, he says.

“The salary in Nepal’s army is very low, so many of them prefer serving in the armed forces abroad,” Bahadur adds.

Some military analysts in India have pointed out that the Modi government’s Agnipath scheme is a means to save funds to modernise the country’s military.

But at a speech in July in which Modi paid tribute to the Indian soldiers who lost their lives during the 1999 Kargil War, the prime minister said that the Agnipath scheme was not for financial reasons and was the military’s project. He said the scheme “will increase the strength of the country and the capable youth will also come forward to serve the motherland”.

Indian opposition leaders including Congress party president Mallikarjun Kharge, however, accused Modi of “doing petty politics even on occasions like paying tribute to martyrs” and called for the scheme to be scrapped.

Overseeing his young men doing 50 push-ups each, Bahadur says joining the Indian Army financially benefitted him as well.

“While my father and grandfather were also in the army and that inspired me to join, I wanted to earn well, and India seemed like the best option,” he explains. “It also has good educational facilities and throughout my postings across the country, my son and daughter got to pursue their studies and are employed in well-paying jobs in India today. I wish the young boys I’m training today get such an option in the future.”

More than 32,000 Gurkhas currently serve in the Indian Army and, according to Bahadur, prior to Nepal pausing recruitment, between 1,300 and 1,500 young Gurkhas would be recruited into the Indian Army every year.

“We do some rigorous training programmes which prepare the young boys to join any army in the world,” Bahadur says. “The physical training includes the boys carrying the famous ‘doko’ a bamboo bag filled with 15kg of sand and sprinting uphill in the Himalayan ranges,” he said. “We also hold theory classes on all subjects ranging from mathematics to general knowledge, since they have written exams to pass to get recruited to armies abroad.”

“While training helps, we Gurkhas are natural fighters known to be fearless, loyal and disciplined, making us an asset to any army,” Bahadur adds.

Twenty-year old Ujwal Rai comes from the Okhaldhunga district in eastern Nepal, which is dominated by the Rai community, an ethnic group in Nepal known to send its sons to join armies around the world. He agrees with Bahadur.

“Our community resides in eastern Nepal and we are born fighters. Being Gurkha soldiers is in our genes,” he tells Al Jazeera.

Clad in a black and red jacket and shorts, and doing pull-ups, Ujwal reminisces about his conversations with his grandfather who served in the Indian Army.

“He would tell me about the kind of battles they trained for but also spoke highly about the food in the Indian Army mess. I would have loved to follow his footsteps but now since I don’t have that option, I’m training to join the Singapore Police Force,” he says.

Every year, there are about 20,000 Gurkha applications for the British Army with 200-300 hired. There are currently more than 4,000 Gurkhas employed in the British Army. Meanwhile about 2,000 Gurkhas currently serve in the Singapore Police Force with nearly 150 hired every year.

Lack of employment options in Nepal

Many young men from Nepal choose to go abroad to join armies as there are not enough employment prospects in the country, which had unemployment of 12.6 percent between 2022 and 2023, according to a June report from the country’s National Statistics Office.

“Serving in your country’s armed forces is an honour for all of us. But financially, there is not much money I can earn by serving in Nepal’s army. I’m training to join the British Army and serve the UK, with an aim to be able to financially support my family,” 19-year-old Priyash Gurung, who also attends the British Gurkha Training Centre in Pokhara, tells Al Jazeera.

According to Bahadur, the monthly starting salary for a soldier in Nepal ranges from 27,000 to 30,000 Nepali rupees [$199.34 – $221]. By comparison, the Singapore Police Service pays a starting monthly salary of just over $3,000 to a young soldier.

“That’s a lot of money in Nepal considering that many of the boys come from poor families and such a lumpy salary can go a long way in helping them,” he said.

Jaya Prakash Gurung, a former British Army Gurkha and managing director of the British Gurkha Training Centre, shared a similar view.

He added, however, that while there are benefits of joining armies abroad, cases of discrimination do exist.

“When I was in the British Army, the British soldier was paid more than Nepal’s Gurkha. The Gurkhas including former Gurkhas protested this discriminatory payment scheme and today reforms have been made to ensure there is equality,” he tells Al Jazeera while sipping a cup of tea at his training centre.

“I find India’s new army recruitment scheme discriminatory today. It is unfair and what will a young Gurkha do after four years of training? We have been a part of the Indian Army for decades and the government of Nepal and India should discuss a solution to resume recruitment, keeping the future of our young boys in mind,” he says.

Turning to Russia

The lack of options if they don’t get selected into the British Armed Forces or Singapore police, has also pushed some young men to try more dangerous alternatives – like joining the Russian army, with the hopes of earning more money.

Nepal and Russia do not have an agreement which allows Moscow to recruit soldiers from the country. While Kathmandu does not have details of the exact number of Nepali mercenaries currently in Russia fighting for it against Ukraine, CNN reported in February that Moscow has recruited about 15,000 men from Nepal. So far, at least 40 Nepali soldiers have been killed in Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Ramesh Bishwakarma, known to his friends as “Diamond”, says he decided to join the Russian army for financial reasons. He is currently fighting in Kursk.

“I had previously fought in the Maoist People’s War in Nepal and had risen to the position of battalion co-commander of the People’s Liberation Army,” Bishwakarma tells Al Jazeera.

Between 1996 and 2006, about 17,000 people were killed when the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) launched a “people’s war” against state forces, seeking to abolish the country’s monarchy. A peace accord was signed between the warring parties on November 21st, 2006, bringing an end to the war.

After the war, in 2008, the government led by then Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai decided to integrate the Maoist army into the Nepali Army.

“That’s when my wife, younger brother and I decided to return home on voluntary retirement. Since then we began subsistence farming, animal husbandry, and sold groceries to meet our family expenses,” the 38-year-old tells Al Jazeera.

But the income in Nepal was just not enough to cover their household expenses, according to Bishwakarma. This made him consider rejoining the armed forces, but this time in Russia.

“I paid for my ticket and visa to Moscow and as soon as I reached the city, I saw pamphlets advertising the process to join the Russian army … It also mentioned the address and location of the central military recruitment centre in Moscow and I took a taxi to the recruitment centre,” he says.

A man at the recruitment centre who spoke English was responsible for coordinating the recruitment of foreigners, he recalls.

“The basic monthly salary I get here is 210,000 roubles ($2,088), and I get an allowance between 25 to 100 percent which depends on the number of days I spend in the war. The salary is credited to my account in a government bank which is under the Russian army. I then transfer the money to my friend who works in Moscow and he sends it to my family in Nepal,” he says.

Bishwakarma adds that he was attracted by Russian history which resonates with him – after fighting for a communist army in Nepal.

“I could have gone to join the army of any other country to earn more money. I could have also joined the Ukrainian army, but Russia seemed suitable, because Russia (formerly the Soviet Union) is a country where Vladimir Lenin established a socialist system by carrying out an armed rebellion against the Tsarist regime in 1917.

“I, myself, read the history of the revolution in the Soviet Union, so it was natural for me to choose the path of joining the Russian army ideologically and emotionally. Where money, self-respect and self-satisfaction are being provided,” he adds.

Captain Bahadur says that while he has heard of cases of men from Nepal going to join the Russian army, he does not believe that many have trained at Gurkha centres.

While young boys may be facing a lack of options, he encourages them to study or try other jobs if they are not selected to join the British or Singapore army.

What do future prospects look like?

Talks between India and Nepal over the Agnipath scheme currently remain deadlocked.

India’s army chief, General Upendra Dwivedi, did not mention the subject during his recent visit to the country in early December for talks on improving military ties between the neighbours. Diplomatic relations between New Delhi and Kathmandu are currently tense since Nepal’s new Prime Minister, KP Sharma Oli, is seen by India as leaning towards China.

Nepal’s government did not respond to Al Jazeera’s request for comment on whether it plans to resume allowing recruitment to the Indian Army.

Meanwhile, at their training ground in Pokhara, Shishir and Ujwal say that irrespective of what decision and rules governments make in the years to come, “all armies are equal” in the eyes of a Gurkha fighter.

“We are Gurkhas. Our motto that says ‘it’s better to die than be a coward’ motivates us to fight, and we will fight with complete loyalty for whichever army we are selected into,” Shishir says, as he and Ujwal continue their army training, carrying their dokos.

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/12/30/why-nepals-gurkha-fighters-want-to-join-indias-army-again?traffic_source=rss