Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

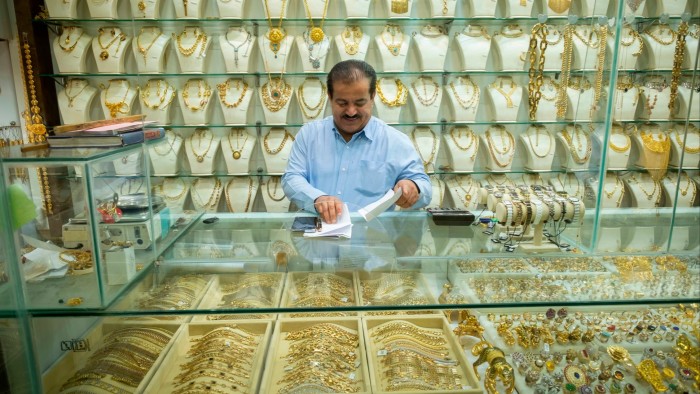

One morning in a labyrinthine Tehran bazaar, a salesman was pitching a hot investment to shoppers. “Your money is dead,” he said of the country’s beleaguered currency, the rial. “Buy gold.”

Local prices for gold in Iran have outpaced a worldwide surge over the past year, as businesses buy the metal to skirt sanctions and ordinary Iranians invest to protect their savings amid the threat of military confrontation with the US and Israel.

The price of gold coins in the country has risen more than 80 per cent over the past 12 months in rial terms, from IR401mn to IR735mn (approximately $900). This compares with a 45 per cent increase in the global benchmark over the same period.

Some analysts fear a precarious bubble has formed as the country’s economy becomes increasingly dependent on the metal, with some Iranians losing money after the start of nuclear talks with the US — and hopes of sanctions relief — sparked a correction from local record highs.

But as bullion enjoys a historic worldwide rally, the demand from Iran — which is the world’s fifth-largest consumer of gold bars and coins — has given the global market an extra boost.

Iran imported a record 100 tonnes of gold, worth about $8bn, in the 12 months up to late March, the end of the country’s financial year, according to government data. Analysts say the actual volume could be double that figure, with much coming from nearby markets such as the United Arab Emirates and Turkey.

Majidreza Hariri, head of the Iran-China Chamber of Commerce, likened gold to a weapon Iran could use to defend its economy. “If other countries run their economies like conventional armies, we operate like guerrillas,” he said. “Today it might be gold, tomorrow [cryptocurrency] Tether, and so on.”

Analysts also believe the Central Bank of Iran has built up sizeable gold reserves — possibly larger than ever before — to serve as a buffer against future sanctions. The bank declined to comment on the matter.

“No one in the world can stop Iran from importing gold,” said one economist, who asked not to be named. “The global gold market is opaque. Gold takes up little space and much of it arrives through neighbouring countries.”

Until recently, the government actively encouraged non-oil exporters to dodge banking restrictions by accepting payment in bullion.

But authorities appear to have quietly halted their support for this in recent months, reportedly suspending tariff-free gold imports around late March, though they have not explained why.

Extreme volatility has also hurt some savers. Prices for gold coins briefly surged above IR1bn towards the end of March, before the start of talks with the US sparked a correction.

Fatemeh, a 24-year-old housekeeper from Tehran, who bought 16 grammes of unworked bullion near the peak of the market, subsequently lost the value of her investment after selling at a lower price.

“I was not looking to make a profit,” Fatemeh said. “I just didn’t want to lose my family’s savings. But sadly we did.”

Yet with the obstacles to a nuclear deal with the US considerable, demand for gold continues, even if at a slower pace.

American officials have repeatedly said they want Iran to stop enriching uranium, something the Islamic republic has ruled out. As talks continue, President Donald Trump has maintained his “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran and has issued threats and further sanctions targeting crude exports — the country’s main source of foreign revenues.

Meanwhile, Tehran has increased its stockpile of highly enriched uranium to record levels in recent months.

Given the ongoing risks, many Iranians are believed to be stashing gold and US dollars at home, bypassing the banking system. “It’s like wine that just sits in storage,” said Mohammad Keshtyaray of the Gold and Jewellery Special Committee.

Local media frequently report thefts. Mina, 72, recently returned home from two weeks’ holiday to find that all the jewellery she had kept in her bedroom was gone. Nothing else was stolen.

This financial bubble around gold has not helped craftspeople and jewellers, who say demand for decorative gold — which has long played an important role in Iranian culture — is suffering like the rest of the economy.

“There was a gold market in Isfahan a thousand years ago,” said Ali, a gold trader in one of Tehran’s bazaars. “Now, it’s not that women have lost interest — it’s that they’ve lost purchasing power.”

Additional reporting by Leslie Hook in London

https://www.ft.com/content/b6b80ce7-6baa-4a72-837c-a0fd1db6128e