No place in Syria was more feared than Sednaya prison during the Assad family’s decades-long, iron-fisted rule.

Situated on a barren hilltop on the outskirts of Damascus, the capital, Sednaya was at the heart of the Assads’ extensive system of torture prisons and arbitrary arrests used to crush all dissent.

By the end of the nearly 14-year civil war that culminated in December with the fall of President Bashar al-Assad, it had become a haunting symbol of the dictator’s ruthlessness.

Over the years, the regime’s security apparatus swallowed up hundreds of thousands of activists, journalists, students and dissidents from all over Syria — many never to be heard from again.

Most prisoners did not expect to make it out of Sednaya alive. They watched as men detained with them withered away or simply lost the will to live. Tens of thousands of others were executed, according to rights groups.

The New York Times visited Sednaya several times, including the day after the regime fell. We interviewed 16 former prisoners and two former prison officials, and built a comprehensive 3-D model of the prison using more than 130 videos filmed on site by journalists for The Times who surveyed the vast complex.

We also spoke with prisoners’ relatives and a prisoner advocacy group to corroborate the details surrounding their arrests.

Former prisoners told The Times that they were tortured, beaten and deprived of food, water and medicine. Some of them saw prisoners or were themselves beaten by doctors responsible for treating them, leaving them swollen and often bleeding until they died.

Some of the former prisoners’ accounts included descriptions of violence that could not be independently verified, but that were largely consistent with one another and with rights groups’ reports on Sednaya.

Family members in search of missing relatives foraged through papers inside Sednaya.

Daniel Berehulak/The New York Times

Our reporting uncovered new details of the systemic torture and inhumane conditions the Assad government used to break anyone who dared to speak up against it.

Sednaya was so feared that few in Syria dared to utter its name. After rebels ousted Mr. al-Assad, the prison was suddenly open to the public for the first time.

The prison complex was constructed in 1987 and included a Y-shaped main building, which rose four stories above ground.

Over the course of the civil war, more than 30,000 prisoners died at Sednaya, many executed in mass hangings, according to rights groups. Amnesty International described it as a “human slaughterhouse.” The true death toll from Sednaya remains unknown.

Former prisoners who had been imprisoned in the past few years told us that every few weeks, guards rounded up dozens of prisoners to execute them.

“Every day we asked ourselves, ‘Will they execute us now?,’” said Mr. al-Diq, the former rebel. “‘What will they do with us today?’”

From Cage to Dungeon

The prisoners typically arrived at the Sednaya complex bundled in cargo trucks, blindfolded and with their wrists shackled, former prisoners told us.

When the back door of the truck swung open, guards corralled them into an intake area at the main prison building, barking at them to keep their heads down and beating them with batons.

Then, prisoners were forced to squat with their heads between their legs as guards registered their names.

The inmates were told to strip naked and forced into metal cages that lined the walls.

Cages about two feet deep and six feet tall lined the walls of the prison’s intake room.

Daniel Berehulak/The New York Times

When peaceful protests against the regime in 2011 turned into a civil war, Mohammad al-Buraidi, 32, a musician from the southern city of Daraa, was training on the oud — a pear-shaped string instrument.

He joined the rebel movement to defend his hometown from government forces. After a crackdown on the rebels, he laid down his arms, and in 2022, complied with a government mandate to join its military. Within months of doing so, he was arrested and accused of continuing to support the rebels, charges he denied.

By the time Mr. al-Buraidi arrived at Sednaya, he, like most former prisoners The Times talked to, had already endured months of torture in filthy dungeons and detention facilities across the country. Mr. al-Buraidi said he spent a month in prison in Damascus hanging from the ceiling by his hands for multiple hours a day before he was transferred to Sednaya.

The guards instructed the men that their lives now revolved around three rules, according to former prisoners. Do not ask for food or water. Do not touch the cell door or ask for help. If a cellmate dies, leave his body there.

The prisoners were given a few small pieces of bread.

Some men resorted to licking sewage water off the floor. They slept sitting up, Mr. al-Buraidi said, so their bodies would not be covered in feces.

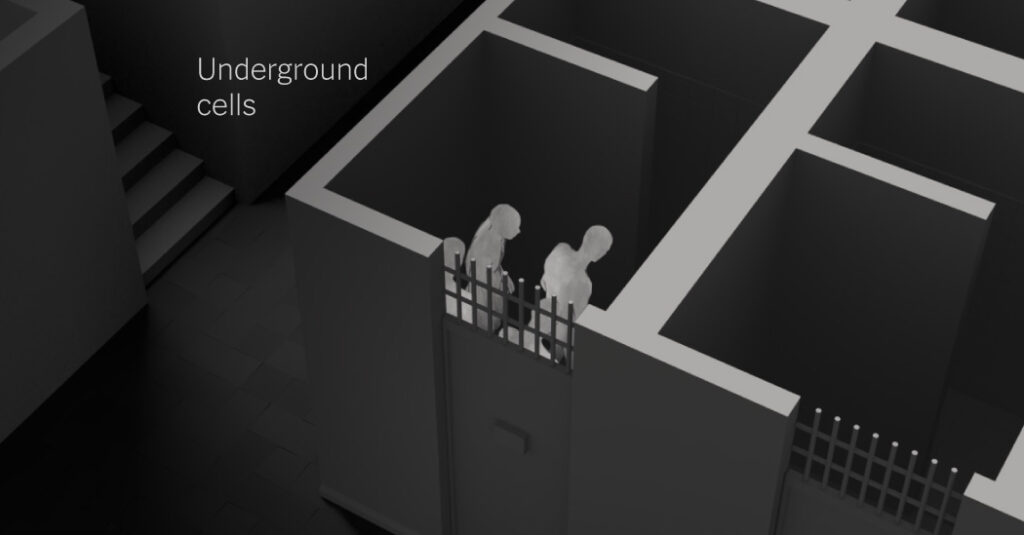

Mr. al-Uthman, 30, spent eight days in an underground cell after he was arrested in 2020. It was summer and the cell was suffocating, he said.

“It’s so hot and stuffy down in the underground cell that after a couple of days, you start begging — not for your freedom, but to at least be taken up to the group cells,” he said.

When one of his cellmates collapsed and lost consciousness, Mr. al-Uthman and the other inmates panicked.

A cellmate yelled out for help. The guards yanked open the door and dragged the collapsed man into the hallway, beating him with batons and pulverizing his hands and legs.

Then they tossed him back into the cell. For days, Mr. al-Uthman tried to revive the man, collecting his own urine in his cupped hands to try to get him to drink.

The man regained consciousness but died two months later, Mr. al-Uthman said.

Where Death Was Always Near

After a week or so in underground cells, prisoners were moved to group cells spread across three wings on the top three floors of the building.

Mr. Mouma, 33, who was arrested in 2018, spent six years in Sednaya. He moved to a new cell every few months, he said, as waves of cholera and tuberculosis seized the prison.

The days began around 6 a.m., when prisoners woke up to the sound of metal clanking, as guards did their daily rounds. Guards often ordered the prisoners to kneel at the back of the cell, facing away from the door, according to two former prisoners.

Then they asked if anyone had died.

“We had to tell the officers that we have a ‘carcass’ — not a ‘martyr’ or ‘someone who had died,’” Mr. Mouma said. “We couldn’t even say the word ‘body,’ otherwise they would kill you.”

A doctor accompanied the guards. The most notorious one was known to prisoners only as “The Butcher.” During rounds, his gruff voice bellowed across the prison, sending chills up Mr. Mouma’s spine.

If a prisoner asked for medical help, the Butcher typically yanked him out of his cell and beat him unconscious, Mr. Mouma and other prisoners said. The Butcher threatened to kill anyone who looked him in the face.

Prisoners received minimal food. A single bowl of yogurt to share among 20 people. Sometimes a bit of bread or some cheese. If they were lucky, they would get a few eggs.

The guards often taunted the prisoners, stepping on their food or purposely spilling it on the prisoners’ blankets as they delivered it.

“I can’t even describe the meals they’d bring us,” Mr. Mouma said. “Not even a dog would be willing to eat this.”

Clothes, bowls and blankets left inside a cell at Sednaya prison after the regime’s fall.

Daniel Berehulak/The New York Times

With every passing month in Sednaya, Mr. Mouma grew more gaunt, his skin pale and fragile, draped across protruding bones. He prayed he would not be beaten. He prayed he would live one more day.

Those who managed to survive the conditions still faced the prospect of death by execution after being sentenced in sham trials.

Every two weeks, guards banged on the iron gates of each wing and read out a list of names of those being summoned for executions, according to eight former prisoners.

In desperation, some who heard their names ran to the bathroom in their cells to hide. Others reluctantly stepped out, knowing their fate was sealed.

At the start of the civil war, prisoners were taken from the main building to a small room in the basement of another building 500 feet away.

A building where executions once happened is next to the main prison building.

Emin Sansar/Anadolu via Getty Images

There they were hanged in the presence of several people, including the prison director, according to two prison officials. The prison officials spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

An Unlikely Reunion

The only contact some prisoners had with the outside world came once every couple months when family members were allowed to visit for a few minutes.

In the visitation hall, the prisoners and their loved ones were kept several feet apart and separated by floor-to-ceiling bars. A corridor patrolled by a guard separated the prisoners from their visitors.

After the regime fell, family members looked for signs of missing relatives in the prison’s visitation area.

Daniel Berehulak/The New York Times

For some prisoners, the visits brought a different kind of pain. Mr. al-Uthman — the Homs native arrested in 2020 — recalled how his cellmate’s visit with his wife and newborn daughter for the first time since he was arrested was too much.

In the weeks that came after, his cellmate stopped eating and drinking. He sat in the corner of their cell, refusing to speak with anyone except a hallucination of his wife. Months later, he died, Mr. al-Uthman said.

Other prisoners found a glimpse of hope in the visits.

Sitting in the visitation room nearly two years into his incarceration, Mr. al-Abdallah, 27, heard the guards shout a name he recognized: Akram al-Abdallah, his younger brother.

Years earlier, Mohammad and Akram had given up their dreams of becoming doctors to join the rebels in their neighborhood in Homs, the brothers said.

In the waiting room, Mohammad looked up and saw Akram — gaunt, tired, a shell of the brother he knew. Mohammad could recognize him only by his voice.

“It was like I had died, and suddenly my soul came back to me,” Mohammad said. Until that moment, Mohammad had not realized that Akram was also in Sednaya.

The two later learned that Khalid, their youngest brother, had also been held there for years, only to die while incarcerated.

Mohammad al-Abdallah held a photograph of his brother Khalid.

David Guttenfelder/The New York Times

Around six months before the regime fell, Akram ended up being transferred to the cell next to Mohammad, the brothers said. Akram had fallen sick and was weaker than ever.

Every night, the two brothers would talk to each other through small openings in between their cells — the sound of their voices a rare comfort.

Freedom for Those Still Alive

Most of the prisoners could not imagine ever leaving Sednaya.

Then, on Dec. 8, 2024, the unfathomable happened.

In the middle of night, the prisoners suddenly heard a commotion and the prison staff yelling. A little while later, they could hear the whop-whop of a helicopter landing on the roof. Then gunshots, the rattling of iron bars and screams of “Allahu akbar,” “God is great.”

On the night they were liberated, some men left their cells on the first floor of Sednaya’s main building.

Source: Scopal, via Reuters

With little access to the outside world, most prisoners were unaware of the rebels’ lightning advance — and confusion and terror filled their cells.

Mr. al-Diq, who was grabbed at a checkpoint in 2019, thought that prisoners were rioting and flattened himself on the ground, too terrified to move.

Mr. al-Buraidi and his cellmates ran to the bathroom of their cell, as men forced open the door to their wing with the butt of a rifle. When they shot open his cell door, the men shouted: “Go, go wherever you want in Syria,” Mr. al-Buraidi recalled. “You are free now!”

When Mohammad and his brother Akram made it out of their cells, they embraced, Akram collapsing in Mohammad’s arms.

Mr. al-Uthman began running down the road from the prison, convinced for miles that his newfound freedom was a farce and that guards would appear out of nowhere to throw him back in Sednaya.

Mr. Mouma stumbled out of the prison complex in incredulity.

“We couldn’t believe it, and we had no idea what to do,” he said. “It was ecstasy beyond description.”

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/08/29/world/middleeast/syria-sednaya-prison-assad.html