Île d’Ambre, Mauritius – It is claimed to be the place the place the final dodo was sighted. Yet, immediately, Île d’Ambre, an islet off the northeastern coast of Mauritius fringed by vibrant inexperienced mangroves, stands as a logo, not of extinction, however of survival.

As information Patrick Haberland explains, huge swaths of mangroves had been destroyed proper as much as the mid-90s, ripped up for firewood or to clear the way in which for boat routes and lodge building tasks.

Cutting down mangroves is now forbidden by legislation. Following a nationwide conservation drive, websites like Île d’Ambre have since been restored. Now it’s a nationwide park, protected by the federal government’s forestry division.

Having escaped extinction, the timber at the moment are very important to the very survival of the nation. Their dense, tenacious roots are among the many island’s principal strains of defence, together with the coral reef and seagrass beds, towards rising tides which can be eroding its silvery seashores, gobbling up 20 metres of shoreline over the previous decade.

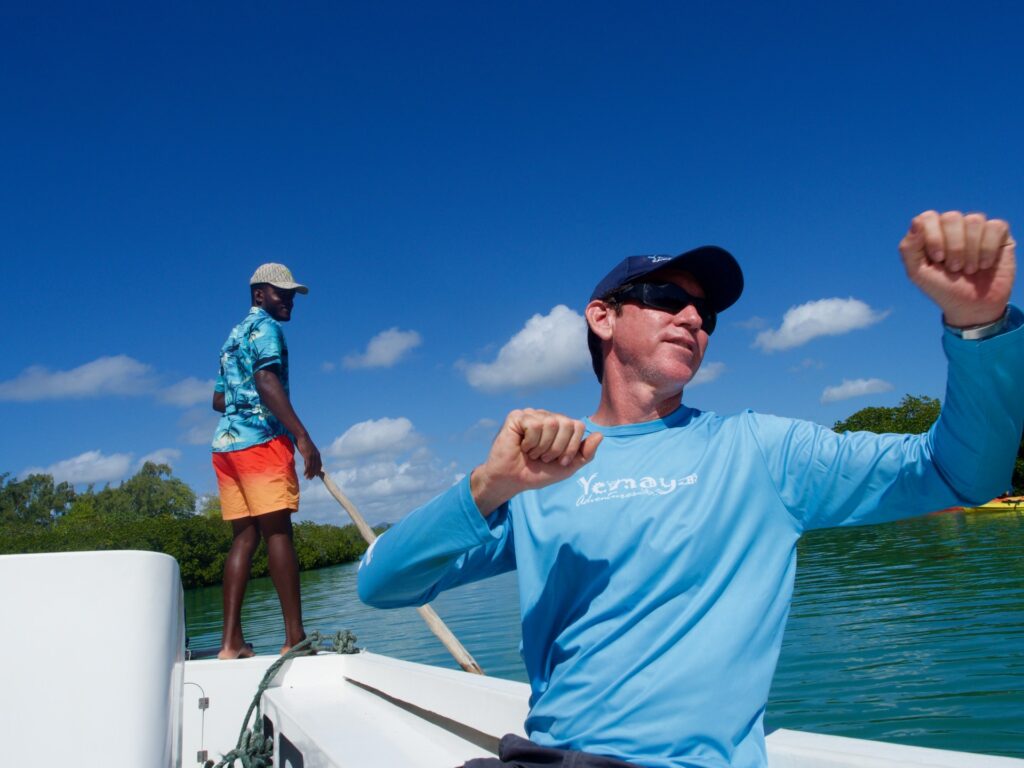

It’s a predicament that weighs closely upon Haberland, who runs Yemaya Adventures, a small firm taking vacationers on canoeing journeys by means of the mangroves. He is one among a rising variety of locals advocating a back-to-nature method to tourism. “The environment provides us with our livelihood. If we don’t respect it, we won’t have work,” he says.

‘Killing the golden goose’

As vacationers flock right here in ever higher numbers – up by almost 60 % throughout the first half of this yr – the island finds itself in a quandary. How can it maintain an trade that has not solely strained its fragile ecosystems but additionally contributed to international local weather change that’s in flip bleaching its reefs and inflicting sea ranges to rise by an alarming 5.6mm a yr?

“It’s killing the golden goose, destroying the environment,” says activist Yan Hookoomsing, of the nonprofit Mru2025. As Hookoomsing factors out, the lodge trade continues to be increasing. Back in 1997, the federal government’s “Vision 2020” plan for the trade set a “green ceiling” of 9,000 lodge rooms for the complete nation. Recently, tourism minister Steven Obeegadoo introduced 19 new lodge builds that can convey that whole near 16,000.

With tourism numbers on the rise, Hookoomsing and his companion, Carina Gounden, are campaigning to fence off the nation’s southern coast, proposing a geopark on the beautiful stretch of shoreline, which options sand dunes, sea cliffs, lava caves, swimming pools, waterfalls, estuaries, lagoons and open ocean.

Currently awaiting authorities approval, the “green lung” undertaking can be a logical transfer for a rustic attempting to offset its dependence on tourism with sustainable land use insurance policies – solely 4 % of native forest is left, the results of intensive cane cultivation going again to the mid-Nineteenth century.

Hookoomsing and Gounden fell in love whereas campaigning to kick lodge builders off Pomponette, a public seaside within the south – a battle they lastly gained in 2020. Like so many different lodge tasks, it will have seen locals excluded from their shores. “We need to think about how we share these spaces,” says Gounden. “You can’t just tell the public to move away.”

“Mauritians feel like second-class citizens,” she provides. “There’s a feeling of losing something that made them happy, the beauty of their country. This affects the way we welcome tourists.”

No extra greenwashing

“The baseline of what is acceptable is changing,” says Vikash Tatayah, conservation director on the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation.

He’s banking on vacationers serving to to drive the transfer in direction of sustainability. Right now, the inspiration is creating area of interest ecotourism actions that can permit guests to spend time with native researchers. Eco-volunteerism is one other potential development space, enabling vacationers to take part in conservation.

Nature is without doubt one of the island’s principal attracts, he says. “People come from the four corners of the globe to see the kestrels and the pink pigeons. Some come to see rare reptiles. Others come for the rare plants like the tambalacoque (dodo tree) or the mandrinette hibiscus.”

“One thing hotels and companies won’t be able to do in the future is greenwashing – we got rid of all our plastic cups, so we’re ecological,” he provides. “Tourists will want to know the environmental policy of the countries they visit. They will want to know hotels are working on conservation and that staff are locally employed.”

Aware of the altering temper, the posh market can be getting in on the act. Local group Rogers has repurposed the previous sugar property Bel-Ombre, relaunching the world as a form of ecotourism mecca. Its three inns supply carbon-neutral packages integrating solar energy and water repurposing initiatives, offsetting emissions by means of the African carbon credit scheme Aera.

The inns are positioned in a buffer zone on the UNESCO-recognised Black River Gorges National Park-Bel Ombre Biosphere Reserve. Covering greater than 8,500 hectares (32.8sq miles), the reserve is seen as a mannequin for eco-friendly growth, bringing again endemic timber such because the black ebony and offering a house for uncommon native species just like the Mauritian flying fox and the pink pigeon.

Equitable change

Change appears inevitable, but it surely must be equitable whether it is to be actually sustainable, analysts say.

“We need to change sea, sand and sun to restoration, recycling and respect,” says oceanographer Vassen Kauppaymuthoo. “The environment can be used as a transformative tool for tourism. If eco-tourism is presented as an opportunity where people can participate, giving them back confidence, then we can have this spark.”

To a sure extent, he thinks this transformation would require an extended, onerous take into consideration the nation’s identification, reversing current tendencies which have seen it copying glitzy locations like Dubai and Singapore. Failure to do that correctly may see the sector, which represents 1 / 4 of gross home product (GDP), going the way in which of the dodo, he says.

But if there’s something this small nation excels at, it’s survival. Back in 1968, when Mauritius took its first steps as an impartial nation, with solely sugarcane mono-crops to its identify, it was predicted to fail. By the 90s, it was being hailed as a mannequin for the African continent.

“At the end of the day, we are resilient,” says Kauppaymuthoo. “We’re used to radical change.”

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/12/6/we-are-resilient-mauritius-slowly-consolidates-ecotourism-gains?traffic_source=rss