An estimated 100,000 scores and parts by the groundbreaking 20th-century composer Arnold Schoenberg were destroyed last week when the wildfires in Southern California burned down the music publishing company founded by his heirs. The company rents and sells the scores to ensembles around the world.

“It’s brutal,” said Larry Schoenberg, 83, a son of the composer, who ran the company, Belmont Music Publishers, from his home in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles and kept the firm’s inventory in a 2,000-square-foot building behind his house. “We lost everything.”

Belmont’s catalog offered a wide range of Schoenberg’s music, from the lush, hyper-Romantic pieces of his youth to the challenging works he wrote after breaking from conventional tonal harmony and developing his 12-tone technique.

No original Schoenberg manuscripts were destroyed in the fire. But the loss of Belmont’s collection could create problems for orchestras, chamber music groups and soloists planning performances of Schoenberg’s works in the months ahead. Other Schoenberg memorabilia was also destroyed in the fire, including photographs, letters, posters, books and arrangements by other composers of Schoenberg pieces.

Leon Botstein, the president of Bard College and the music director of the American Symphony Orchestra, said that Belmont played an essential role in making Schoenberg’s music available to the public. The American Symphony Orchestra got its scores for a performance of Schoenberg’s oratorio “Gurrelieder,” which it performed last year at Carnegie Hall, from Belmont.

“It’s a catastrophe,” Mr. Botstein said. “It was an indispensable resource.”

He added that some ensembles could be forced to make changes to their upcoming programs because the scores they need will not be available from Belmont.

“They were the lenders, they were the ones who helped you out,” he said. “They made it as easy as possible.”

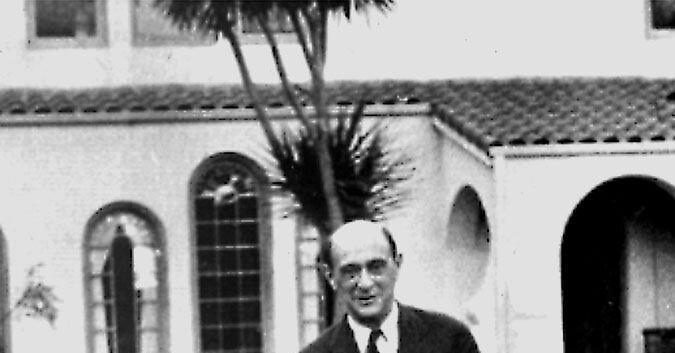

While Belmont, established in 1965, is not the only publisher of Schoenberg’s works, the firm was revered for the authority of its scores and its connection to the composer, who was born in Vienna, fled the Nazis and moved to America. He eventually settled in Los Angeles, where he lived until his death in 1951.

Belmont said it would work on creating digital versions of its scores, based on manuscripts by the composer, which are kept at the Schoenberg Center in Vienna. Belmont kept digital backups of scores at its offices, but they also burned in the fire.

“There’s a finality here which is astonishing,” said Larry Schoenberg. “There’s no hope left that you’re going to find or retrieve anything. And that’s a different kind of grief.”

Musicians said they were devastated by the loss of Belmont.

The cellist Fred Sherry, a noted Schoenberg interpreter, was a regular visitor to the outbuilding that became known as Belmont’s “garage.” He recalled perusing hundreds of scores, including some with old-school cover art and type. He took home as much music as he could carry.

“The loss of those beautiful scores is a tragedy,” Sherry said, “but meanwhile the music will last for as long as we have concerts.”

Larry Schoenberg, whose home was also destroyed in the fire, said he was still coming to terms with the scale of the loss. He recalled the example of his father.

“Whenever there was a difficulty, he would express his frustration, then get to work on a solution,” he said.

“Despite all that has happened, we are trying to be very positive,” he added. “There are no tears here.”