The writer is professor of economics at Harvard University and author of ‘Our Dollar, Your Problem’

US fiscal policy is running off the rails, and there seems to be little political will in either party to fix it until a major crisis occurs.

The 2024 budget deficit was a mind-blowing 6.4 per cent of GDP; credible forecasts suggest that the deficit will exceed 7 per cent of GDP for the rest of President Donald Trump’s term. And that is assuming there is no black swan event that once again causes growth to crater and debt to balloon. With US debt already exceeding 120 per cent of GDP, it seems a budget crisis of some sort is more likely than not over the next five years.

True, if markets trusted US politicians to prioritise fully repaying bond holders — domestic and foreign — above all else, and not to engage in partial default through inflation, there would be nothing to worry about.

Unfortunately, if one looks at the long history of debt and inflation crises, the overwhelming majority occur in situations where the government could pay if it felt like it. Typically, a crisis is catalysed by a major shock that catches policymakers on their back foot, when debt is already very high, and fiscal policy inflexible.

Certainly the One Big Beautiful Bill Act preserves the tax cuts from Trump’s first term, which in all likelihood helped spur growth. However, the evidence from several rounds of tax cuts going back to Ronald Reagan in the 1980s suggests that they do not nearly pay for themselves. Indeed they have been the major contributor to the steady run-up in debt during the 21st century. And Trump’s new tax bill contains a raft of highly distortionary add-ons — no tax on tips, overtime or social security — that are not helpful. Not surprisingly, the Congressional Budget Office concluded that the bill would add $2.4tn to debt over the next decade.

The real problem for politicians is that American voters have become conditioned to never having to deal with sacrifice. And why should they?

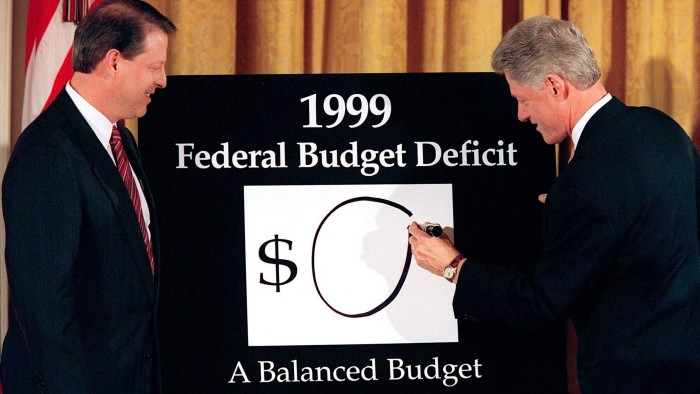

Since Bill Clinton last balanced the budget at the end of the 1990s, both Republican and Democratic leaders have tripped over themselves to run ever larger deficits, seemingly without consequence. And if there is a recession, financial crisis or pandemic, voters count on getting the best recovery that money can buy. Who cares about another 20 to 30 per cent of GDP in debt?

What has changed, unfortunately, is that long-term real interest rates today are far higher than they were in the 2010s. Between 2012 and 2021, the inflation-indexed 10-year US Treasury bond yield averaged around zero. Today, it is over 2 per cent and, going forward, interest payments are likely to be an ever-larger force pushing up the US debt-to-GDP ratio. Real interest rises are far more painful today than they were two decades ago, when US debt to GDP was half what it is now.

Why are real rates rising? One reason, of course, is record global debt levels, both public and private. This is only part of the story, however, and not necessarily the most important part.

Other factors — including geopolitical tensions, the fracturing of global trade, rising military expenditures, the prospective power needs of AI and populism — are all important. Yes, inequality and demographics arguably push the other way, which is why a number of prominent scholars still believe a sustained return to ultra-low real interest rates will ultimately save the day. But should the US, which aims to be global hegemon for another century or more, be betting the farm on this?

Indeed, although long-term interest rates may fall, it is equally possible they may rise with the US 10-year rate, now around 4.5 per cent, eventually reaching 6 per cent or more. The rise will be exacerbated if Trump succeeds in achieving his dream of a lower US current account deficit, the flip side being less foreign money coming into the US.

It will also be exacerbated if, as I argue in my latest book, US dollar dominance is now fraying at the edges as China continues decoupling from the dollar, Europe remilitarises and cryptocurrencies take market share in the massive global underground economy.

Trump’s tariff wars, threats to tax foreign investment and efforts to undermine the rule of law will only accelerate the process. Indeed, if he succeeds in achieving his dream of closing up the US current account deficit, the reduced inflow of foreign capital will push US interest rates up further, and growth will also suffer.

Just because the US debt trajectory is unsustainable does not mean it needs to end dramatically. After all, instead of allowing interest rates to continue drifting up, the government can invoke growth-stifling Japanese-style financial repression, keeping interest rates artificially low and thereby converting any crisis into a slow-motion crash.

But slow growth is hardly a desirable outcome, either. Inflation is the more likely scenario given the centrality of finance to US growth, with the government (whether Trump or a successor) finding a way to undermine the independence of the Federal Reserve. The US’s high debt and inflexible political equilibrium will be a major amplifier of the next crisis and, in most scenarios, the American economy and the dollar’s global status will be the losers.

https://www.ft.com/content/812a06b0-2819-4a75-abaf-455722cf63e8