In Summary

- Traditional African outfits such as agbadas, kente cloth, and Herero gowns reflect cultural identity, social status, and heritage.

- The bold colours, intricate patterns, and beadwork of African attires carry symbolic meanings tied to rituals, ceremonies, and community traditions.

- These garments preserve cultural memory, strengthen community bonds, and celebrate artistry across generations.

Deep Dive!!

Wednesday, 26 November 2025 – Africa’s traditional fashion carries centuries of history, identity, and artistry, expressed through fabrics, patterns, and colours that tell the stories of entire communities.

From bold handwoven textiles to intricately beaded garments, the continent’s cultural wardrobe stands as one of the richest in the world. These outfits do more than clothe the body, they preserve heritage, celebrate status, and reflect the creativity that defines Africa’s diverse societies.

This article highlights ten of the most colorful traditional dresses across the continent, each chosen for its cultural significance, craftsmanship, and visual appeal. Whether showcased at festivals, ceremonies, or everyday life, these garments reveal the beauty and pride woven into African culture. Through this list, readers can experience the vibrant spirit of African fashion and the traditions that continue to inspire designers today.

10. Maasai Shuka (East Africa)

The Maasai Shuka is more than a simple blanket; it is a vibrant, wearable flag representing one of Africa’s most iconic cultures. This large, rectangular cloth, typically a striking, solid red, is draped over the body and secured with a knot over the shoulder. While red is the most common and symbolic colour, representing courage, strength, and blood, which is essential to life, the Shuka also appears in bold blues, checkered patterns of purple and pink, and energetic stripes of orange and yellow. These colours are not chosen at random; they often signify specific age sets or social statuses within the complex Maasai warrior society, with younger moran (warriors) often favouring the most vibrant hues to display their vitality and energy.

The Shuka’s functionality is as important as its symbolism. Worn in the vast, open savannahs of Kenya and Tanzania, the thick cotton or polyester material provides protection against the harsh sun, thorny bushes, and chilly nights. Its simple draping allows for freedom of movement, essential for the Maasai’s pastoral lifestyle. In recent years, the Shuka has transcended its traditional role, becoming a powerful symbol of East African identity and a source of inspiration for global fashion designers and tourists seeking an authentic connection to the region’s cultures. It is a testament to a people who have fiercely maintained their traditions while sharing their distinctive aesthetic with the world.

What many may not know is that the ubiquitous red Shuka is a relatively modern adaptation. Historically, Maasai clothing was made from softened animal skins, which were durable but monochromatic. The shift to commercially produced cloth in the 20th century opened up a new world of color, which the Maasai enthusiastically embraced, incorporating their existing symbolic color code into this new medium. Furthermore, the way the Shuka is worn, the knotting, the layering, and the accessories paired with it, can convey subtle messages about the wearer’s mood, intentions, and current role in the community, making it a dynamic and communicative form of dress.

9. Toghu (Cameroon)

The Toghu (or Atoghu) is a regal textile from the Northwest Region of Cameroon, a garment so rich in symbolism and artistry that it is often referred to as the “African Tuxedo.” It consists of a heavy, black velvet background upon which intricate, elaborate patterns are embroidered with vibrant golden, red, and white thread. The designs are not merely decorative; they are a complex visual language featuring geometric shapes, stylized representations of animals like spiders (for wisdom) and crocodiles (for authority), and other cosmological symbols that speak to the history, philosophy, and social structure of the Bamileke, Kom, and other Tikar peoples.

Traditionally, Toghu was exclusively the attire of royalty, chiefs, and notables, with the density and complexity of the embroidery indicating the wearer’s rank and wealth. It is worn during the most significant life events: coronations, funerals of important figures, traditional weddings, and cultural festivals. The process of creating a single Toghu is incredibly labor-intensive, requiring a skilled artisan weeks or even months to complete the meticulous cross-stitch embroidery by hand, making each piece a unique and valuable heirloom passed down through generations.

A fascinating aspect of Toghu is its evolution into a modern symbol of Cameroonian national pride. While it retains its royal prestige, it is now worn with pride by everyday citizens, especially during national holidays and university graduation ceremonies, representing a unified cultural identity. Furthermore, the knowledge of the specific patterns is a form of intellectual property guarded by the communities. To the untrained eye, it is a beautiful pattern, but to the initiated, it tells a specific story about lineage, social standing, and ancestral blessings, making the Toghu a wearable archive of Cameroonian history.

8. Kente (Ghana)

Kente cloth is arguably Africa’s most famous and visually spectacular textile, a masterpiece of weaving that originates from the Ashanti Kingdom of Ghana. Woven on a traditional wooden loom, Kente is characterized by its dazzling, multicolored stripes and complex geometric patterns, each with a name and a deep philosophical meaning. The colours are intentionally symbolic: gold represents royalty, wealth, and spiritual purity; green signifies growth, harvest, and renewal; blue stands for peace, harmony, and love; and red evokes passion, political fervor, and bloodshed. A single cloth can contain over a dozen different colors, each carefully chosen to convey a specific message or prayer.

Originally, Kente was reserved for Ashanti royalty and was worn only during sacred ceremonies and important state functions. The Asantehene (the Ashanti King) and his court would wear specific patterns that communicated their status and power. Today, while still a symbol of prestige, Kente has been democratized and is worn by Ghanaians and the African diaspora for significant occasions like weddings, graduations, and religious ceremonies. It is not merely clothing but a source of immense cultural pride, a tangible connection to a glorious past and a statement of African excellence on the global stage.

What many may not know is that the true value of a Kente cloth lies in its patterns, not just its colors. Each design, such as “Obaakofoo Mmu Man” (literally “A king has many advisors”) or “Sika Fre Mogya” (“Money draws blood”), conveys proverbs, historical events, or ethical values. Furthermore, authentic Kente is handwoven in narrow strips that are then meticulously sewn together to form a larger cloth. The wearing of Kente is also governed by etiquette; it is traditionally draped over the left shoulder for men and worn as a wrap for women, ensuring that the beautiful patterns are displayed to their full effect, telling their silent, powerful stories.

7. Djellaba (Morocco)

The Moroccan Djellaba is the epitome of elegant, everyday modesty, a long, loose-fitting robe with long, wide sleeves and a pointed hood (qob). While often seen in neutral shades for daily wear, the Djellaba truly reveals its colorful soul during festive occasions.

For these events, women and men don Djellabas crafted from luxurious fabrics like silk, brocade, or fine wool, in a breathtaking palette of fuchsia, emerald green, cobalt blue, and sunshine yellow. The beauty is in the details: intricate embroidery, known as tarz, adorns the cuffs, neckline, and front opening, often using metallic threads in gold and silver to create dazzling floral, geometric, or calligraphic motifs.

The Djellaba’s design is a masterclass in practicality and cultural adaptation. The full sleeves and flowing cut allow for air circulation in the heat and modesty in accordance with cultural norms. The distinctive pointed hood, large enough to cover a traditional fez, serves as a pocket for small items or can be used for warmth.

Regional variations are pronounced; the Djellabas of cities like Fes are renowned for their elaborate, multi-colored embroidery, while those from Rabat might feature more subtle, white-on-white stitching. This garment seamlessly blends Berber, Arab, and Andalusian influences, reflecting Morocco’s rich history as a cultural crossroads.

A captivating detail is the role of the Djellaba in the modern Moroccan wardrobe. It is a unisex garment that transcends age and social class, worn by everyone from market vendors to government officials. The choice of a Djellaba for a specific event, a wedding, a religious holiday like Eid, or a family visit, is a careful decision, with the color, fabric, and intricacy of the embroidery communicating the wearer’s taste, social standing, and the importance of the occasion. It is a garment that allows for both personal expression and strict cultural conformity, making it a enduring and dynamic symbol of Moroccan identity.

6. Herero Gowns (Namibia)

The Herero gown, or Otjikaiva, is one of Africa’s most visually striking and historically poignant garments, a powerful symbol of resilience and cultural reclamation. Worn by Herero women in Namibia, its form is a direct, Victorian-style adaptation: a long, voluminous dress with a high neck, puffed sleeves, and an enormous, floor-length skirt supported by multiple petticoats. However, the Herero people have made this colonial import uniquely their own. The fabrics are vibrantly colored, bold prints, and the most iconic element is the headdress, a horn-shaped hat (otjikalva) made from the same fabric, which symbolizes cattle horns, the cornerstone of traditional Herero wealth and spiritual life.

The history of the gown is a complex narrative of conflict and identity. Introduced by German missionaries and colonists in the 19th century, the dress was initially imposed. However, following the traumatic genocide of the Herero people by German forces in the early 20th century, the survivors began wearing the gown as a form of quiet defiance and cultural preservation. They adopted the structure but subverted its meaning, choosing their own colorful fabrics and incorporating the symbolic headdress to assert their Herero identity. Today, wearing the gown is an act of pride, a way of honoring the ancestors who endured immense suffering.

What many may not know is the strict etiquette and significance surrounding the gown. It is primarily worn for ceremonial purposes, at weddings, funerals, and annual Herero Day commemorations, where thousands of women parade in these magnificent dresses to honor their fallen chiefs and ancestors. The number of petticoats, the style of the sleeves, and the pattern on the fabric can indicate a woman’s regional origin, marital status, and social standing. The Herero gown is thus much more than clothing; it is a walking memorial, a declaration of cultural survival, and a breathtakingly beautiful testament to a people’s unbreakable spirit.

5. Boubou (Senegal)

The Boubou (or Grand Boubou) is the quintessential garment of elegance and prestige across West Africa, with Senegal being one of its most celebrated homes. This majestic, flowing robe is a masterpiece of tailoring, consisting of a large, rectangular piece of fabric with a wide, often round, neckline and an open front. Its grandeur lies in its simplicity and the spectacular fabrics from which it is made. Men’s and women’s Boubous are crafted from vibrant, high-quality damask, bazin, or brocade, and are frequently adorned with intricate, matching embroidery along the neckline, front opening, and cuffs. The colors are deliberately chosen to impress, with rich indigos, shimmering whites, and deep purples being particularly popular.

Wearing a Boubou is an art in itself, conveying a sense of dignity, composure, and wealth. It is the attire of choice for the most important social and religious events: Friday prayers at the mosque, weddings, naming ceremonies, and major holidays like Korité. The swish of the fabric and the way it drapes the body commands respect. In Senegalese society, a beautifully embroidered Boubou is a significant investment and a key component of a family’s wardrobe, often gifted for special occasions and worn for years. It is a symbol of “Terranga” (Senegalese hospitality), as dressing impeccably for guests is a sign of respect.

A fascinating detail is the role of the Boubou in the Senegalese economy and fashion scene. The fabric, especially bazin riche, is a luxury item, and the embroidery work provides a livelihood for countless skilled artisans. Furthermore, Senegalese women are globally renowned for their fashion sense, and the Boubou is at the center of a dynamic and competitive sartorial culture. Women will have their Boubous tailour-made for specific events, and the style, color, and intricacy of the embroidery are closely watched and admired, making it a dynamic and ever-evolving tradition that perfectly balances deep-rooted custom with cutting-edge style.

4. Agbada (West Africa)

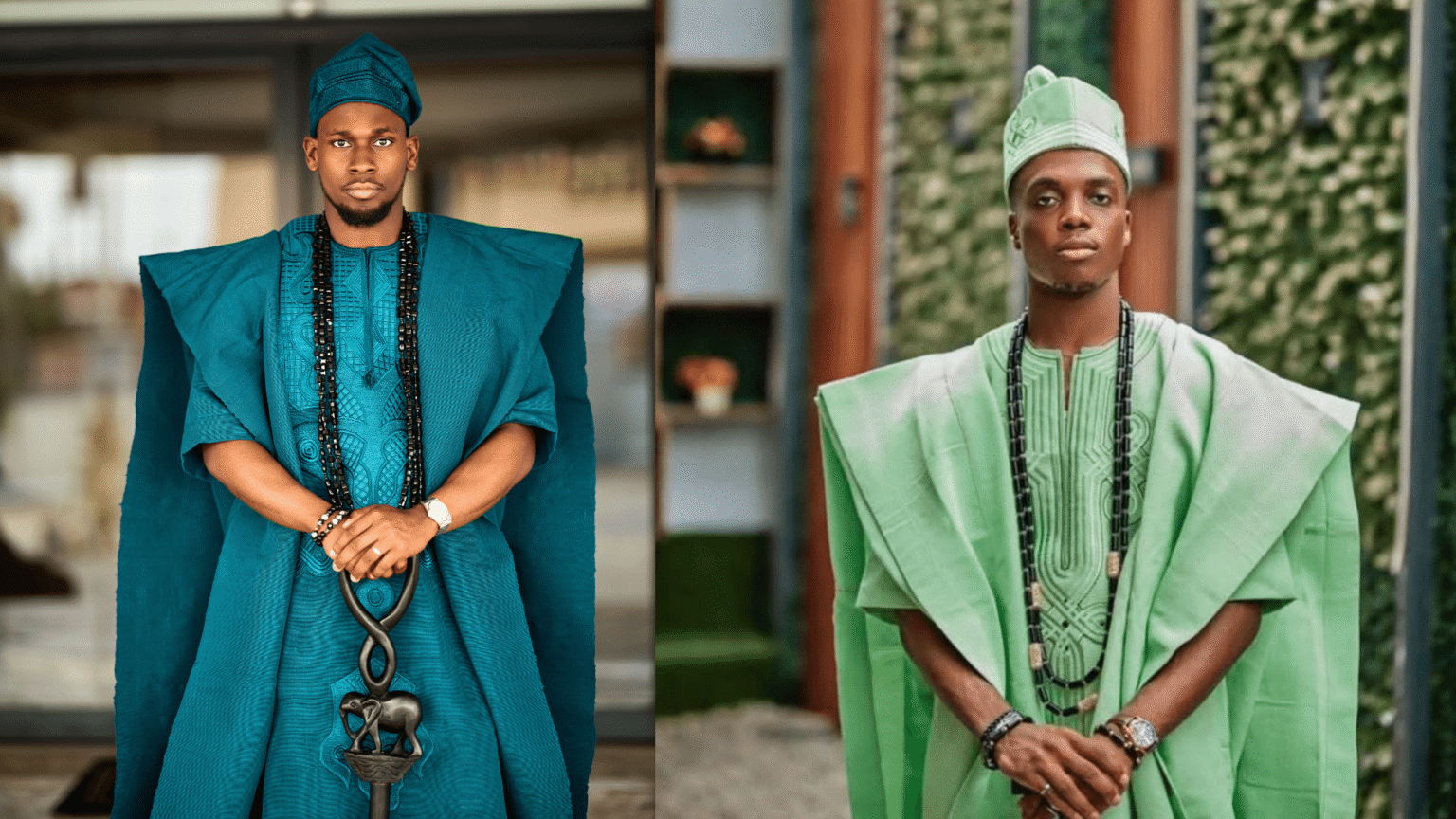

The Nigerian Agbada is a garment of immense presence and grandeur, a sweeping, wide-sleeved robe that exudes authority and sophistication. Worn primarily by men, it is a three-piece ensemble consisting of the large, flowing outer robe (agbada), a long-sleeved undershirt (awotele), and tailoured trousers (sokoto). The power of the Agbada lies in its volume and its decoration. It is made from richly coloured and often heavily embroidered fabrics, with the neckline and front panel serving as a canvas for elaborate, ornate patterns stitched in metallic or contrasting threads. The sheer amount of fabric and the complexity of the embroidery are direct indicators of the wearer’s wealth, social status, and taste.

Historically, the Agbada was the attire of kings, chiefs, and elders among the Yoruba, Hausa, and other ethnic groups across West Africa. It was a garment of state, worn in royal courts and during important judicial or political gatherings. Today, it remains the definitive formal wear for significant life events: it is the quintessential groom’s attire at a traditional wedding, the preferred dress for politicians on the campaign trail, and the ceremonial garb for chieftaincy title holders. When a man enters a room in a well-tailoured Agbada, it commands immediate attention and respect, signaling his importance and connection to tradition.

The sleeves are so wide that they can be thrown over the shoulder with a dramatic flourish, a practical adaptation for the heat that has become a stylish gesture. Furthermore, the choice of embroidery pattern is often deeply personal or symbolic, incorporating motifs that represent the wearer’s family history, profession, or aspirations. The Agbada is more than clothing; it is a performance of identity, a mobile piece of architecture, and a powerful, colorful statement of Nigerian cultural pride that continues to evolve while holding fast to its regal roots.

3. Shweshwe (South Africa)

Shweshwe (pronounced shwe-shwe) is a distinctive printed cotton fabric that has become a cornerstone of traditional and contemporary South African fashion. Known for its crisp texture and sharp, geometric patterns, Shweshwe is most recognizable in its classic indigo blue, brown, and maroon hues, though it now comes in a wide spectrum of colours. The fabric is named after the 19th-century Sotho King, Moshoeshoe I, who was gifted similar cloth by French missionaries, but its origins can be traced back to indigo-dyed fabrics traded by European settlers. Over time, it was wholeheartedly adopted and transformed by Xhosa, Sotho, and Zulu women into a powerful symbol of their own cultural identity.

The process of creating authentic Shweshwe is unique. The fabric is roller-printed, which gives the designs their precise, white outlines, and is then treated with a starch that gives it a characteristic stiff feel and a subtle, pleasant scent. This stiffness requires a special technique to work with, and the fabric must be washed before sewing to soften it. Shweshwe is used to create a variety of garments, from the elegant, high-necked dresses and aprons worn by Xhosa women for ceremonies and weddings to modern skirts, shirts, and even accessories, seamlessly bridging the gap between tradition and trendy urban style.

A fascinating aspect of Shweshwe is its status as a cultural unifier in post-apartheid South Africa. While strongly associated with specific ethnic groups, it has been embraced as a national fabric, representing the “Rainbow Nation’s” diverse heritage. Furthermore, the patterns themselves often have names and meanings, referencing everyday life, history, or natural elements. The production of Shweshwe is now a proudly South African industry, guarding its traditional methods fiercely. This humble, durable cloth has become a vibrant, wearable canvas for telling the story of South Africa’s past, present, and future.

2. Gomesi (Uganda)

The Gomesi, also called the Busuuti, stands as one of Uganda’s most recognisable cultural treasures, celebrated for its rich colours and graceful silhouette. Worn by women across several ethnic groups, particularly the Baganda, the dress blends tradition with elegance in a way that immediately captures attention. Its vibrant fabrics, often made from silk, satin, or polished cotton, shimmer beautifully in the sunlight and bring a sense of ceremony to any gathering.

What makes theGomesiespecially striking is its unique design. The broad, square neckline, the dramatic puffed sleeves, and the signature sash tied around the waist create a distinctive look that is both regal and expressive. Each element of the dress carries a cultural meaning, from the way it is wrapped to how it is accessorized. The result is a garment that not only enhances beauty but also communicates identity, respect, and social grace.

In Uganda, the Gomesi is reserved for important occasions like weddings, introduction ceremonies, and cultural festivals, where it serves as a powerful symbol of heritage. Its bold colours and intricate tailouring make it one of Africa’s most eye catching and meaningful traditional outfits. As African fashion continues to inspire global trends, the Gomesi remains a proud reminder of Uganda’s artistic legacy and the enduring strength of its traditions.

1. Ndebele Traditional Dress (South Africa)

The Ndebele people of South Africa claim the top spot with a traditional dress that is a breathtaking fusion of textile art, painting, and beadwork, creating one of the most visually spectacular and unique forms of adornment on the continent. The attire of married women is particularly magnificent, consisting of thick, beaded hoops (iporiyana) worn around the neck, arms, and legs, and large, stiff, geometric aprons (amajogolo) that are densely covered in intricate beadwork. These are complemented by blankets draped over the shoulders, all working together to create a powerful, colorful, and sculptural silhouette that is unmistakably Ndebele.

The artistry of Ndebele dress is intrinsically linked to their world-renowned mural painting. The same bold, geometric patterns, featuring triangles, diamonds, and sharp, linear forms, that adorn the exterior walls of their homes are meticulously replicated in their beadwork. The colour palette is equally vibrant, utilizing contrasting shades of blue, red, yellow, green, and white to create a striking visual impact. This cohesive aesthetic makes the Ndebele homestead and its inhabitants a living, breathing gallery of cultural expression, where art is not separate from life but is woven into its very fabric.

A crucial and often misunderstood element is the social significance of this dress. The different items of clothing and their specific patterns are a direct reflection of a woman’s stage in life. The most elaborate and heavy beaded pieces are worn by married women, with the iporiyana neck rings symbolizing the bond of marriage; a wife would only remove them upon the death of her husband. The knowledge of these patterns and the skill to create them are passed down through generations of women, making the dress a powerful symbol of female identity, creativity, and cultural continuity. It is not just clothing; it is a masterclass in geometric art, a map of social structure, and a vibrant, proud declaration of Ndebele identity.

We value your thoughts. If you have comments or feedback about this article, reach out to our Editor-in-Chief at [email protected].

https://www.africanexponent.com/top-10-most-colourful-traditional-dresses-in-africa/