The proliferation of documentaries on streaming services makes it difficult to choose what to watch. Each month, we’ll select three nonfiction films — classics, overlooked recent docs and more — that will reward your time.

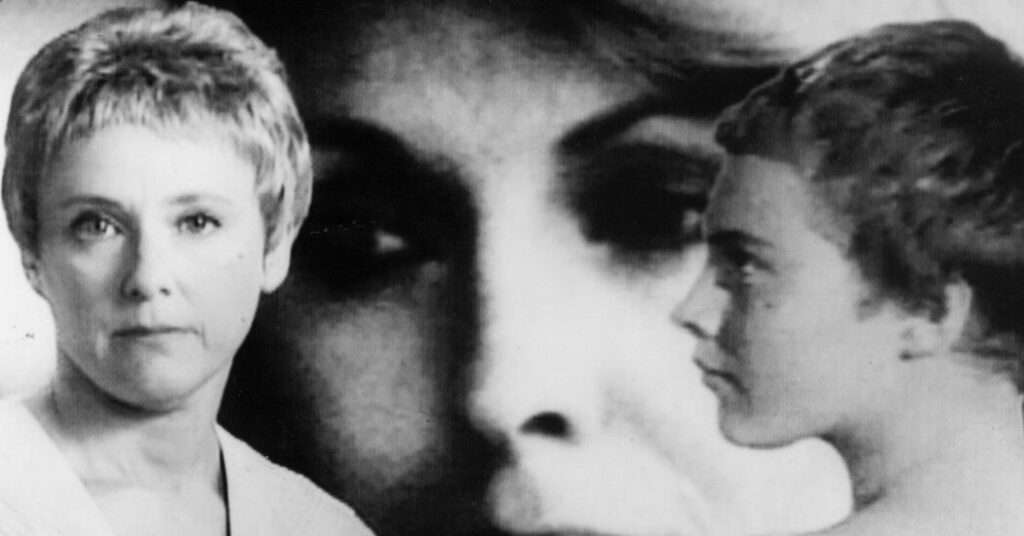

‘From the Journals of Jean Seberg’ (1995)

Rent it on Kanopy, Ovid and Vimeo.

Simultaneously a biography, a cultural history and an effort to see behind the images on the movie screen, Mark Rappaport’s visual essay on the actress Jean Seberg maintains the semblance of telling her story in her words. Seberg, played by Mary Beth Hurt, is the film’s narrator and, in effect, a monologuist, with an astounding assortment of film clips for illustration. Initially, Rappaport’s film appears to be telling a straight life story, as Hurt’s Seberg describes her background and how the director Otto Preminger selected her from countless auditionees to play Joan of Arc in “Saint Joan” (1957). “The bad news was, we made the movie,” Seberg quips. She muses on being miscast and on the curse that seems to follow Joan of Arc movies. “It was the first time I was burned at the stake,” she says as she speaks of catching on fire on set, “but not the last.”

Seberg relates the rest of her period of peak stardom: Preminger cast her more successfully in “Bonjour Tristesse” (1958); Jean-Luc Godard gave her what is almost certainly her most-remembered role, in “Breathless” (1960); and she played a schizophrenic in Robert Rossen’s underseen “Lilith” (1964). The Seberg of “Journals” cites “Lilith” as her “most gratifying work experience,” although she also sounds troubled by what she views as the film’s excessively masculine perspective, and how it emphasizes the way her character takes Warren Beatty’s down with her. Seberg — or “Seberg” — muses on how frequently she locked eyes with the movie camera, something that professional actors aren’t usually supposed to do.

Rappaport cites “Played Out: The Jean Seberg Story,” a biography by David Richards, in the thank-yous during the end credits, but at a certain point it becomes clear that his Seberg is as much an act of channeling — or of imagination — as of history. One through line of the film compares Seberg’s support for the Black Panthers to Jane Fonda’s anti-Vietnam War activism and Vanessa Redgrave’s outspoken advocacy for the Palestine Liberation Organization. Certainly by the time Seberg, who died in 1979 at 40, is talking about Fonda’s workout videos in the 1980s (“She assumes positions that make Barbarella look positively arthritic”), it is clear that “From the Journals of Jean Seberg” is also an act of speculation. Through Seberg, Rappaport poignantly muses on the double standards of history. (In a country “where even Richard Nixon can re-emerge as a distinguished elder statesman,” she says, “it is amazing that Jane’s so-called treasonous behavior is remembered 15 years later.”)

The visual quality of clips, apparently sourced from videotape, looks poor today; it is especially painful to see Otto Preminger’s masterful CinemaScope compositions in “Bonjour Tristesse” cropped for television. But the sharpness of the insights in “From the Journals of Jean Seberg” remains.

‘David Lynch: The Art Life’ (2017)

Stream it on the Criterion Channel and Max. Rent it on Amazon, Apple TV, Fandango at Home and Google Play.

David Lynch, who died earlier this month, really does play himself in this documentary, which is more of an origin story than a career overview: By ending with the making of “Eraserhead” (1977), his first feature, it keeps the focus on the factors that shaped Lynch’s creative world. “I had this idea that you drink coffee, you smoke cigarettes and you paint, and that’s it,” Lynch says of his youthful impression of what it would be like to be an artist. “Maybe, maybe girls come into it a little bit, but basically it’s the incredible happiness of working and living that life.”

The film often shows him working on his paintings, with Lula Boginia Lynch, his young daughter, hanging around. At one point, almost comically, he puts on an Angelo Badalamenti composition for her and bounces her on his knee. The mix of the wholesome and the disturbing seems to have existed for Lynch from an early age. “I never heard my parents argue ever, about anything,” he says. “They got along like Ike and Mike.” But dark clouds started to gather early. Lynch tells the story of, as a child, seeing a naked woman — with a possibly a bloodied mouth — wander out of the shadows and down the street. (This anecdote, often cited as an inspiration for “Blue Velvet,” won’t be new to the devoted Lynchian, but it’s still eerie to hear Lynch tell it.) The family moved from Idaho to Virginia, a place that Lynch says “seemed like always night.”

It was another artist, Bushnell Keeler, the father of a friend, who provided the crucial spark. Even hearing that Keeler was a painter, Lynch says, “blew all the wiring, and that’s what I wanted to do from that second.” He credits Keeler for giving him crucial pushes with both his father and with schooling.

How much comes from the artist’s mind, and how much comes from the way that mind interfaces with life experiences? You may find yourself pondering such heady questions as Lynch describes living in Philadelphia (where, at least back then, he felt a “thick, thick fear in the air”) and recalls the time that his father, horrified by his art experiments, told him he should never have children. California sunshine (“it was pulling fear out of me”) and film school were apparent antidotes. Lynch was known for his reluctance to explain his art, but for this winning and improbably sweet documentary, he was willing to explain his ethos.

‘Black Box Diaries’ (2024)

Stream it on Paramount+.

Of the five features nominated for an Oscar for best documentary this year, one of the most formally inventive is “Black Box Diaries,” directed by the journalist Shiori Ito, who went public with an accusation of rape against a television correspondent in 2017 and became a face of the #MeToo movement in Japan. In the documentary, she chronicles her own journalistic efforts to investigate the case, as well as to grapple with the personal and emotional fallout of what happened to her. (She won a civil suit in 2019.)

At one point, Ito speaks of how, at least initially, she felt the best way for her to revisit these events was from a kind of a third-person perspective. The film shows her in the process of completing a book, “Black Box,” which was published in the United States in 2021, as she tries to get subjects to go on the record, and as she deals with the editing process and with lawyers. There is horrifying security camera footage of her being dragged in a state of apparent semiconsciousness into the hotel on the night the assault was said to have taken place, and there is contemporaneous audio of an investigator at first pushing back on taking the case seriously.

But as its title implies, “Black Box Diaries” is also a first-person film: Ito includes video of herself in emotionally vulnerable states. She also has what would seem to be a justifiable amount of paranoia. (She is shown searching an apartment for wiretaps.) And the movie puts a spotlight on the way Japanese society has historically made it difficult for women to win in sexual-misconduct cases. In footage of the legislature, a lawmaker questions why the man Ito accused of rape was not arrested. “I ask that you stop discussing private citizens in parliament,” the chair says. “We talk about citizens all the time,” replies the lawmaker.