Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

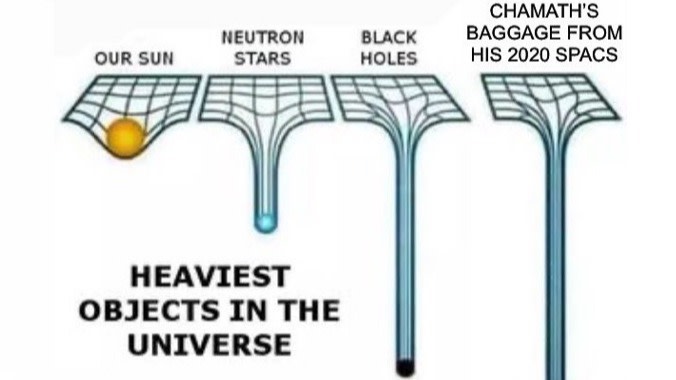

Chamath Palihapitiya is back! The self-styled “Spac King”, whose blank-cheque deals incinerated billions of investor dollars, has announced he’s “probably” launching another one.

That’s despite an abysmal record and the overwhelming thumbs-down verdict of a 58,000-person X (formerly Twitter) poll. “The last time wasn’t a success by any means,” he magnanimously admitted.

Incredible that almost 58k people voted. I hope everyone that voted “No” feels seen.

Now onto business.

I got calls from many Wall Street and Crypto Titans yesterday. They all want in and their vote matters a lot to me so…

I will probably do it.

Maybe this time it will… https://t.co/FXnxKXRTlB

— Chamath Palihapitiya (@chamath) June 19, 2025

That’s one way to put it.

Every investment prospectus includes the standard SEC-mandated health warning: “Past performance is not indicative of future results.” It’s meant to stop investors from blindly pouring money into the latest hot fund just because it’s been on a tear. In Palihapitiya’s case, however, the disclaimer reads less like boilerplate and more like a punchline. Just because nearly all of his previous Spacs have been dumpster fires doesn’t technically guarantee his next one will be too.

Palihapitiya’s timing couldn’t be better: Goldman Sachs is said to be re-entering the Spac business after three years away, and it seems other bulge-bracket investment banks won’t be far behind. And maybe investors are willing to bet on Palihapitiya’s redemption arc and wager that this intelligent, wildly rich man will turn over a new leaf and finally deliver value for others, not just to himself.

Palihapitiya certainly isn’t wrong about the risks. His Spacs have all lagged the S&P 500 since their first trading day, with most either losing a lot of money, a helluva a lot of money, or all of it. Investors in two Spacs that were wound down in 2022 without finding an acquisition turned out to have been fortunate.

Yet here he is, dusting off the old Spac playbook, perhaps on the assumption that collective memory fades like a one-star TripAdvisor review that scrolls out of view. Hope springs eternal, as Alexander Pope wrote. Judgment, less so

But we shouldn’t dismiss Palihapitiya’s latest musings entirely. In a follow-up X post, the former Facebook executive portrayed Spacs as a more transparent, virtuous alternative to traditional IPOs. Banks, he claims, quietly allocate IPO stock to their favoured clients who walk off with easy profits at the expense of employees and early investors.

He cites Circle’s IPO — where shares have soared since their debut — as proof that the process is rigged. According to Palihapitiya, the company left $3bn on the table. “Value is transferred to randoms, and it makes no sense,” he thundered.

This was what I was hoping to fix with SPACs. You may not like SPAC founder promotes or other forms of value transfer to intermediaries but you can never claim it wasn’t disclosed.

The Circle IPO, and ALL traditional IPOS, are the opposite. Value is transferred to randoms and it… https://t.co/3QGTCLxeIL

— Chamath Palihapitiya (@chamath) June 20, 2025

There’s just one teensy-weensy snag: Palihapitiya is the wrong messenger. It’s galling to hear Spac evangelism from someone whose previous blank-cheque (ad)ventures have burned investors so badly. And even when his points aren’t entirely wrong, his analysis is so reductive and self-serving that it’s hard to take seriously.

Yes, IPOs can be underpriced. Yes, banks allocate shares to institutional clients who sometimes flip them for quick gains (although in my experience the companies themselves get heavily involved in deciding allocations). And yes, a big first-day “pop” can mean some of the company’s value has leaked to a few well-connected investors.

But the idea that Spacs are the honest, straightforward alternative is derisory. Spacs have their own set of warped incentives, and Palihapitiya should know that better than anyone.

The core flaw with Spacs is that their structure can encourage bad deals. Spac sponsors get a juicy “promote” — typically 20 per cent of the equity — simply for finding a merger target and getting the deal done, regardless of how the stock performs afterwards. But if they don’t pull it off within two years, they lose the “at-risk capital” of around $5-10mn they put in initially. So the temptation is to do any deal, even a terrible one, just to cash in. Even if the share price later halves, sponsors still walk away with a windfall.

To be fair, Palihapitiya dissolved two of his Spacs in September 2022 with no deal, and investors got their money back, with interest. But by then, Palihapitiya’s Social Capital had already made $750mn in Spacs, and the vast majority of Spac stockholders were redeeming for cash anyway, making it difficult to consummate mergers.

According to Palihapitiya, if the sponsor promote rubs you the wrong way, “you can never claim it wasn’t disclosed.” This is a peculiar way of endorsing the Spac model. He’s openly admitting the flaws — even as he’s reminding you that if you lose money, that’s on you.

As for his IPO critique, it misses the mark. Most deals don’t explode like Circle’s, and when they do, it’s usually about tight supply (ie small free float) and hype, not some grand conspiracy to enrich FOBs (friends of bankers). And while the bookbuilding process has its flaws, at least it tries to discover a market-clearing price by testing demand.

Also, it’s ludicrous to pretend that issuers and their VC backers are helpless victims here. These are sophisticated players who know exactly what they’re doing and often drive the key pricing and allocation decisions.

Spacs, meanwhile, depend on backroom negotiations to set valuations — a process that can be just as subjective (if not more so) than traditional IPO pricing.

The only real market check on comes at two junctures: if Spac stockholders elect not to redeem their shares for cash before the merger, and/or if outside investors commit fresh capital to the merger through a PIPE (“private investment in public equity”, ie where institutions buy shares at a negotiated price).

While this isn’t completely detached from market reality, it’s a far cry from the broader demand-testing of a real IPO, where underwriters canvass orders across the full gamut of institutional and retail investors before setting terms.

Palihapitiya’s real talent isn’t Spacs or venture capital or even podcasting. It’s chutzpah. He has reframed his spectacular failures — from which he has profited enormously — as proof that he has learned the hard way. Because his Spac mergers have been mostly turkeys, you can trust him to know better this time.

It’s the kind of reinvention that could happen only in finance. Or maybe politics.

https://www.ft.com/content/e859c75e-26b0-41a3-a278-8c649178ec77