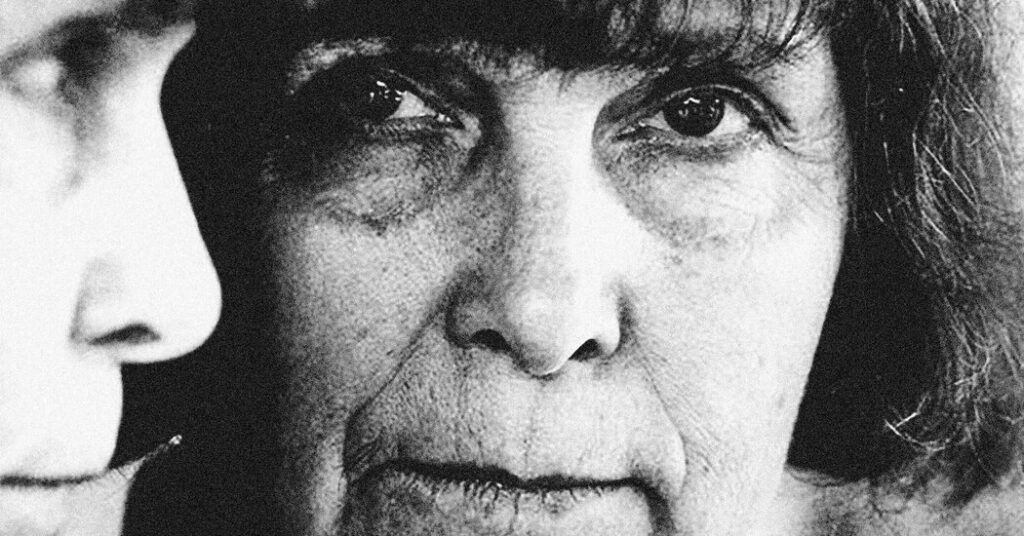

The Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina, who died on Thursday at 93, was that rare creature: an artist both fully modern and sincerely spiritual. “I am convinced that religion is the kernel of all art,” she said in a 2021 interview.

That is hardly a universal worldview these days. The era of Palestrina and Bach, who aimed to glorify God with their work, is centuries past. Music that is adventurous, religious and great is unusual in our secular time, and some of the most significant was written by Gubaidulina.

Hers was never a soothing or tuneful faith. Her music is darker and more bracing than that of, say, Arvo Pärt, whose minimalist spirituality has been co-opted for meditation playlists.

Gubaidulina’s work is not the kind of thing you put on during morning yoga. She makes sounds of struggle and disorder; of awaiting some signal from beyond with hushed anxiety; of the strenuous attempt to bridge the gap between humans and the divine. Transcendence, if and when it arrives, is hard won.

Inspired by Psalm 130, “De Profundis” (1978), a wrenching solo for the bayan, the Russian accordion she loved, begins in the instrument’s depths and rises to harshly radiant heights. Stark focus suffuses “The Canticle of the Sun” (1997), written for the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, a small choir and percussion, and based on a song by St. Francis praising God. Her grand St. John Passion (2000) has apocalyptic force.

She was baptized, as an adult, into Russian Orthodox Christianity, but her beliefs also took in strands from her Tatar father’s Muslim background and her Jewish music teachers. Her openness about her music’s religiosity — and her work’s thorniness — put her in an uncomfortable position with the government in the Soviet Union.

Born in 1931, Gubaidulina was part of the generation that came of age in the wake of Stalin’s death in 1953, allowing her a degree of freedom that musicians a bit older — including Shostakovich, who gave her crucial encouragement early on — were denied. But she still worked within a repressive state.

When her 1980 breakthrough piece, the violin concerto “Offertorium,” was performed a few years later by Gidon Kremer and the New York Philharmonic, John Rockwell, reviewing it in The New York Times, wrote that Gubaidulina “enjoys the good graces of the regime and supports herself writing film music.”

This was not exactly true. Not long before writing “Offertorium,” she was blacklisted by the leader of the powerful Composers’ Union after her work was played at a contemporary music festival in Germany without the state’s approval.

Her travel outside the Soviet Union had already been restricted, but her publication and performance opportunities were further curtailed, and she was closely watched by the KGB. She was physically assaulted at one point, an episode she linked to the limitations that had been placed on her.

Though oppressive, being criticized by the authorities was not the deadly affair it had been under Stalin. Years later, Gubaidulina recalled that “being blacklisted and so unperformed gave me artistic freedom, even if I couldn’t earn much money.”

By the 1980s, governmental disfavor made an artist like Gubaidulina into something of a cause célèbre, giving her more visibility than she might otherwise have had. As her international profile grew during that decade, she received more leeway in terms of travel, and a few years after the Soviet Union collapsed, she moved to Germany, where she lived the rest of her life. Her premieres continued into the 2020s.

It was a recurring criticism of Gubaidulina that her works were overlong. Her concertos were usually single sprawling movements; they could feel like labyrinths, especially given their mood of relentless solemnity. It’s true that most of her pieces don’t fit neatly into the 11- or 12-minute slot typically reserved for contemporary composers at the start of orchestral programs. But I’ve always found her music taut and riveting.

Part of this may be her pieces’ structures, which could be obscure — she had an esoteric method of shaping forms using the Fibonacci sequence of numbers — but can be felt as intention and rigor. Her works go on and on, but you feel as if you’re being led through them by a confident guide.

Few composers have had a more evocative mastery of texture. “Offertorium” — a true masterpiece, especially when Kremer played it with his virtuosic intensity — begins with harsh swoops of violin, redolent of both modernist astringency and a countryside fiddler.

Gubaidulina goes on to offer chilling, diving waves of orchestral sound and screams of trumpet, but also intricate moments of quiet: the solo violin quivering as bells create softly reverberating halos, a flickering violin line that melts into flickering flute.

Later in the piece, the soloist seems unable to stop playing — exhausted yet restless — as a mellow earthiness builds in the orchestra, a slight hint of consolation. A brooding elegy in the violin’s low register gradually travels higher, into a stirring aria with the orchestra glowing around it and a piano slowly charting scales up and down. After 35 minutes, we have moved from raw severity to something close to grace.

Gubaidulina made music that manages to be both uncompromising and accessible. Its strange colors are so alluring and changeable, its sense of drama and timing so sure, its desire to communicate — even if enigmatically — so evident that it’s irresistible. She kept on writing until a few years ago; her 90th birthday was celebrated with recordings and performances around the world.

But she didn’t need a round-number anniversary to be assured of her secure place in the repertory. Last October, the New York Philharmonic played “Fairytale Poem” (1971) just five months after her seething Viola Concerto — unusual frequency for a living composer.

“Fairytale Poem” is not one of her most famous works. The piece was inspired by a Czech children’s story in which the main character is a piece of chalk that wants to draw gardens and castles but is stuck in the classroom doing schoolwork. Then a boy takes it home and finally gives it free imaginative rein.

“The chalk is so happy,” Gubaidulina wrote, “it does not even notice how it is dissolving in the drawing of this beautiful world.”

Hardly a religious subject, but the atmosphere of mysterious vibration gives it a kind of spiritual luminousness. Whether the chalk is a metaphor for the life of an artist — particularly a life under authoritarian rule — is left ambiguous to the vaporous end.