Scott Boras maintains the base of his agenting empire in an office complex in Newport Beach, Calif., but in the afternoons during the baseball season the headquarters shifts location. Sometimes Boras holds court in a suite before games at Angel Stadium. When the Los Angeles Dodgers are in town, as they were throughout October, he stands behind the backstop as a procession of current and future clients, plus suitors for those players, pay him visits.

The rules of Major League Baseball forbid Boras, or any agent, from stepping onto the field. So people come to him.

In the hours before Game 1 of the World Series, Juan Soto made the short pilgrimage into the seats to chat with his agent and several Boras Corporation lieutenants. About half an hour earlier, New York Yankees general manager Brian Cashman had made a similar trip. And two weeks prior, before Game 1 of the National League Championship Series, New York Mets owner Steve Cohen left the diamond to gab with Boras.

The tableau offered a symbol of this winter’s most prominent free-agent contest, the battle between the two New York clubs for the services of Soto, “the Mona Lisa of the museum,” as Boras described him. It also offered a symbol of a question that could define baseball’s next few months: After an offseason viewed as unsuccessful by his rivals, can Boras still make the industry come to him?

During the past four decades, no agent has been more effective at extracting money from baseball’s ownership class than Boras, even in an era where more and more teams are emphasizing austerity. His clients netted more than $1 billion in free agency after the 2019 season. He figures to easily surpass that number this winter. Boras represents eight of the top 16 free agents, according to The Athletic. Soto will command the highest price tag, with a present-day value expected to exceed Shohei Ohtani’s heavily deferred $700 million deal. But the rest of his client list includes former Cy Young Award winners (Corbin Burnes, Blake Snell), a former home run derby champ (Pete Alonso) and a crucial cog on two championship teams (Alex Bregman).

“It’s the talent that runs the sport,” Boras said last week at the General Managers meetings in San Antonio, Texas.

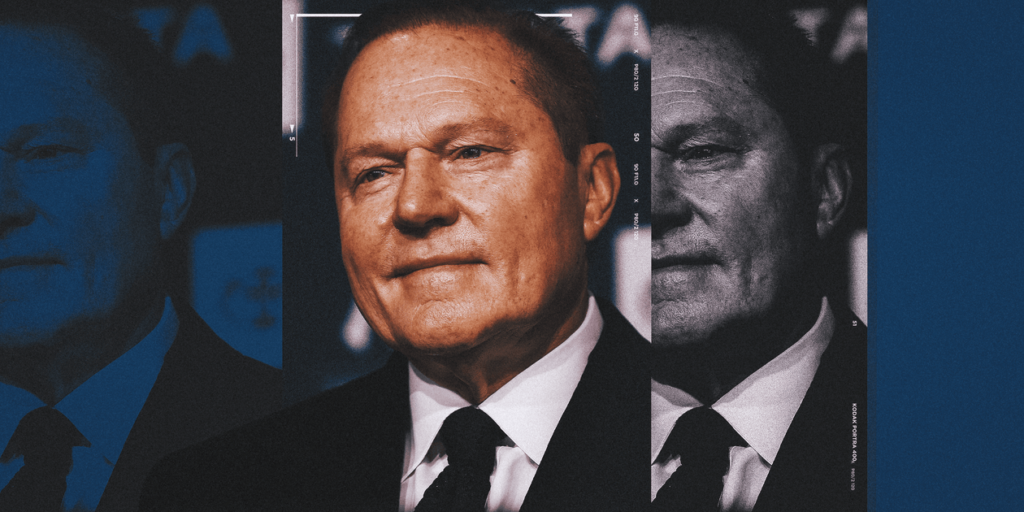

Scott Boras and Juan Soto spoke on the field before Game 1 of the World Series. (Kevork Djansezian / Getty Images)

No agency has more available talent than he does this winter. He will take the group to the market facing a gale of headwinds not dissimilar to the challenges he faced last winter, according to interviews with MLB executives and rival agents, who requested anonymity to speak freely. Some teams continue to grapple with the uncertainty about television deals. Some owners are wary of spending when the expanded postseason offers easier access to a championship. And some executives are increasingly skeptical about the value of long-term contracts for pitchers.

This winter will test the ability of Boras, still spinning out linguistic gems and advocating for his clients at 72, to sell the commodity around which he has built his business — and his influence.

It is not uncommon for Boras to enter the winter as the representative for the best players available. His agency targets high-profile talents before they enter the draft. He also excels at persuading established big leaguers to dump their agents for his services, as he did in recent years with Alonso, Bregman, Burnes, and Snell. With notable exceptions, like Bregman’s Astros teammate Jose Altuve, Boras clients tend to pursue their perceived value on the open market.

In the winter after 2019, Boras brought three former first-round picks to free agency. He had little trouble finding suitable deals for pitcher Gerrit Cole (nine years, $324 million with the New York Yankees), third baseman Anthony Rendon (seven years, $245 million with the Los Angeles Angels) and pitcher Stephen Strasburg (seven years, $245 million with the Washington Nationals). The Strasburg contract set a record for the largest sum ever awarded a pitcher — a deal smashed by Cole days later. The $814 million trio formed the core of Boras’s $1 billion winter.

Last offseason, Boras had less success. He was pursuing new contracts for four major clients: former National League MVP Cody Bellinger, third baseman Matt Chapman, pitcher Jordan Montgomery and Snell. The terrain had changed since 2019. The pandemic tempered some of the owners’ enthusiasm for spending. The expanded postseason reduced the incentive for building a truly great team. The collapse of the regional sports network model handcuffed teams like the Texas Rangers. Boras found himself trying to sell clients to owners ready with excuses and executives jaded about the value of long-term contracts for aging players.

It is not hard to find examples. Beset by injuries, Strasburg made only eight appearances during his new Nationals contract. He retired in April. Rendon rarely plays for the Angels. Even Cole, a smashing success in pinstripes, hurt his elbow this past spring, which triggered worries about his long-term health.

“There’s definitely a recognition in the industry that these type of deals don’t always work,” one executive said.

When spring training opened last February, Boras had not yet found deals for his four prominent clients. Bellinger became the first member of “the Boras Four” to sign when he returned to the Chicago Cubs on Feb. 27 with a three-year, $80 million contract that featured opt-outs after the first and second seasons. The others all took similar pillow contracts, short-term deals designed as a springboard for a brighter future. Chapman signed a three-year, $54 million deal with the San Francisco Giants; Snell became his teammate on a two-year, $62 million contract; Montgomery received a two-year, $47.5 million deal from the Arizona Diamondbacks.

Because it took so long for the players to sign, and because none received a nine-figure contract, the perception among team officials and other agents was that Boras had overplayed his hand. Several executives suggested Boras underestimated the severity of the television collapse, which affected 14 teams as Diamond Sports Group, the Bally Sports operator, went through bankruptcy restructuring. The situation has not been totally rectified a year later, but Boras remained dismissive about its effect on spending.

“I think that’s last year’s news,” Boras said at the GM Meetings. “They’ve had time. I think it’s something that they are aware of what the next generation of distribution for their product is.”

Boras has defended the quartet’s contracts by citing the elevated average annual value of each deal and the ease with which each player could return to the market. But only Snell will test free agency this winter. Montgomery left Boras after a wretched season that ended with Diamondbacks owner Ken Kendrick calling the acquisition a “horrible decision.” Bellinger decided to stay with the Cubs. Unlike Montgomery, he remained loyal to his representative. “What stands out to me is how much he cares,” Bellinger said. “He really does care. He cares about me, he cares about my family. And he eats, breathes and sleeps baseball.”

Giants new president of baseball operations Buster Posey, who is also a member of the Giants’ ownership group, had negotiated directly with Chapman to finalize a six-year, $151 million extension in September. The contract demonstrated that owners were still willing to pay a premium for elite players.

Yet Boras had less success with his first gambit of the 2024 offseason. Three days after the World Series concluded, Cole informed the Yankees he was opting out of the final four years and $144 million of his contract. The Yankees could void the opt-out by triggering an additional fifth season at $36 million. A 48-hour standoff ensued. Yankees general manager Brian Cashman relayed the team’s disinterest in adding another year. The team banked on Cole’s zeal to remain with the Yankees and the market’s concern about a 34-year-old pitcher with an elbow injury. Rival executives did not believe Cole could find a new club willing to beat his current deal. In the end, the two sides agreed that Cole could remain on his original contract and take a mulligan on the opt-out. “The Yankees didn’t blink,” one rival agent said.

Cashman declined to puff out his chest when asked about the unusual outcome. He framed the situation as mutually beneficial. “We wanted our player and our ace back, and he certainly didn’t want to go,” Cashman said.

Even so, the opt-out bluff prompted some chuckling last week among attendees in San Antonio, a collection of colleagues who harbor some combination of amusement at Boras’s bombast, grudging respect for his results and irritation at his methods. One executive described Boras as “a little out of touch,” and unwilling to adjust his tactics to the particulars of the market. Of course, Boras heard similar criticism in the winter after the 2018 season, when only two of his clients inked multiyear deals. He responded with the bonanza built around Cole, Rendon and Strasburg. Which is why another executive described Boras’ lack of success last winter as “a one-off shooting star.”

“He’s also got millions of people paid,” the executive said. “He’s one of the best at what he does. I mean, (Los Angeles Dodgers president of baseball operations) Andrew Friedman doesn’t win the World Series every year, and he’s one of the best at what he does.”

Last Wednesday morning, as a crowd of reporters gathered outside conference rooms at the J.W. Marriott San Antonio Hill Country Resort and Spa, Boras stood on a riser. He is the only agent to schedule regular media briefings at both the GM Meetings and the Winter Meetings. The performance even includes a Boras Corporation backdrop. During events often mired by procedural tedium, these events qualify as mandatory, with Boras riffing out metaphors to groans and guffaws.

On Snell, returning after last year’s dry winter: “There’s no doubt that the Snelling salts have created a lot of whiffs. The market has definitely awakened to Blake Snell.”

On Bregman, a veteran of seven postseason teams: “He’s provided the Astros with that infusion of championship blood. I’d say everything about him is AB-positive.”

On Alonso, nicknamed after a certain ursine mammal: “We hear a lot about the bear market for power-hitting first basemen. For Pete’s sake, it’s the polar opposite.”

And then, of course, there is Soto.

“You can really see that owners, general managers, they’re called upon to be championship magicians,” he said. “It’s what they’re asked to do. It’s hard to do, to put together that magic of a championship run. Behind every great magician, obviously, is the magic Juan.”

As Boras spoke, a meeting of executives let out, sending across the carpeted hallway a parade of men in quarter-zip pullovers and athleisure chinos. Some pointed at the scrum and chuckled. A couple snapped pictures. The majority just went about their day, able to learn about Boras’ latest attempts at whimsy on social media.

Scott Boras media sessions have become a spectacle all their own. (Daniel Clark / USA Today)

Boras does not need flights of rhetorical fancy to sell Soto, who turned 26 in October. He is already one of the most accomplished, feared and revered hitters in the game. He offers power, patience and theatrics, along with a championship pedigree. He helped the Washington Nationals win a title in 2019 and demonstrated his vitality in the Bronx this past fall as the Yankees returned to the World Series. In his only season as a Yankee, Soto posted a .989 OPS, hit 41 home runs, drove in 109 runs and led the American League with 128 runs scored.

Soto was projected by The Athletic’s Tim Britton to secure a 13-year, $611 million contract. Given Soto’s importance to the Yankees and Cohen’s endless trunks of money, that estimate may prove low. And the market may not be limited to New York. The Dodgers intend to move Mookie Betts back to the infield, which creates a convenient opening in the corner outfield. Even if the Dodgers only linger around the proceedings, their presence could drive up Soto’s price. “He’s going to get everything he wants, and more,” one executive said.

Boras explained Soto intended to meet personally with interested owners as part of a “very thorough process.” Some bystanders pronounced themselves curious about how quickly Boras would act. “He’s got to get Soto off the board,” one rival agent said. “You can’t have Corbin Burnes and all these other guys waiting around in January.” Others indicated Soto’s perceived price tag will only tie up a handful of big-market teams. “I don’t think it matters,” one executive said. Boras was guarded when asked if Soto needed to sign ahead of the other clients. “That is a great question,” he said. “Unfortunately, it’s not one that I can answer. It’s one that they can.”

The general expectation, coming out of San Antonio, was that Boras would approach a resolution when the industry reconvened in Dallas on Dec. 8 for the Winter Meetings. The Soto sweepstakes will be the most ravenously followed storyline of the offseason. But the results for the other clients may be a better gauge of Boras’s effectiveness.

Bregman, 30, saw his on-base percentage dip more than 50 points below his career average of .366 this past season. He just underwent surgery to remove a bone chip from his elbow. He has not made an All-Star team since 2019. Alonso, who turns 30 in December, also experienced a significant power outage in 2024, with his slugging percentage falling to a career-worst .469. Despite Boras’s pithy line, the market tends to be cautious about first basemen whose production shows evidence of decline.

The pitchers — a group that for Boras also includes Yusei Kikuchi and Sean Manaea — may also need to practice patience. Only two starting pitchers in last year’s class, Yoshinobu Yamamoto and Aaron Nola, signed contracts longer than five seasons. The shorter-term deal with a higher average annual salary has become closer to the norm. Snell experienced that fate last winter despite winning a Cy Young Award in 2023.

Burnes, though, may be good enough to buck that trend. He has surpassed 190 innings in each of the past three seasons and thrived in 2024 while transitioning to the American League East after the Baltimore Orioles acquired him from Milwaukee. He continues to generate outs despite a declining strikeout rate. “These are talents that don’t exist,” Boras said. “We haven’t had anyone on the market like him since Gerrit Cole.”

In the world of Boras’s remarks, his clients often only exist in the context of his other clients. He can create his own reality. Then again, he can often make it manifest.

On the final day in San Antonio, as executives scattered across the country, the New York Post reported that Boras and Soto would soon host a visitor in Newport Beach: Steve Cohen. Hal Steinbrenner, the Yankees owner, was scheduled to pay his own visit soon after. The baseball world is still willing to come to Boras. The rest of the winter will determine the strength of his gravitational pull.

(Illustration: Meech Robinson / The Athletic; Photo: Mike Stobe / Getty Images)

https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5910061/2024/11/12/scott-boras-mlb-offseason-free-agency/