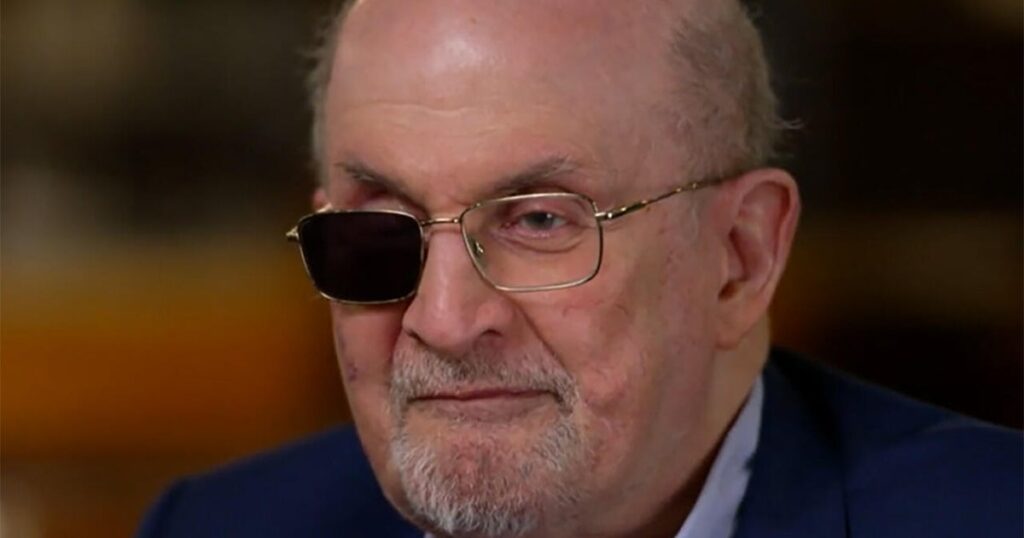

Salman Rushdie recently turned up at a McNally Johnson bookstore near South Street Seaport in Manhattan. “It’s actually not particularly close to where I live, but I come here a lot,” he said.

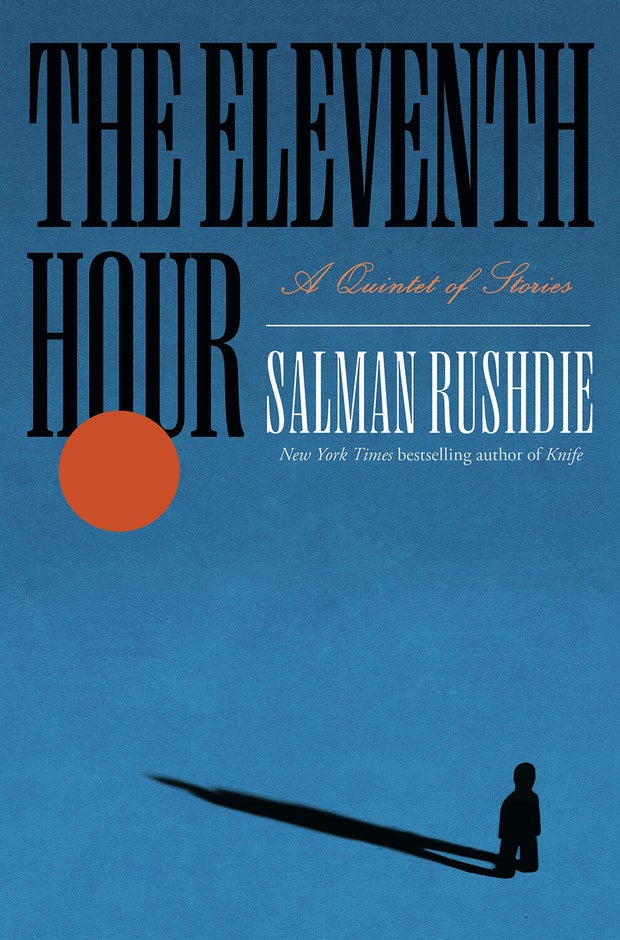

He was browsing for his own books. His newest one, “The Eleventh Hour,” is his 23rd – a collection of short stories and novellas.

Life has changed since the 2022 attack that nearly killed him. “I think what has changed is, for public-facing things, then there has to be security in a way that there wasn’t for 20 years,” he said.

CBS News

On August 12, 2022, Rushdie was on stage in Chautauqua, N.Y., ready to speak, ironically about America as a safe haven for writers. A man lunged at him with a knife.

His account of the attack, “Knife,” was published in 2024: “I raise my left hand in self-defense. He plunges the knife into it. … After that there are many blows, to my neck, to my chest, to my eye, everywhere. I feel my legs give way, and I fall.”

Rushdie lost the sight in his right eye. “I can still read,” he said, “but I do find that I use iPads in a way that I never used to. Because there’s light, and because I can adjust the size of the type. So, I never, ever, read a book on an iPad, but now I do.”

His left hand and liver were badly damaged, but he lived, which he considers “a miracle.”

In May of this year, Rushdie’s attacker, Lebanese-American Hadi Matar, was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Prosecutors argued he was acting on the fatwa, the 1989 order by Iran’s leader, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, to kill the author, claiming passages in his fourth novel, “The Satanic Verses,” insulted Islam.

Recognized just for his fiction before, suddenly Rushdie was world famous (to some, infamous) for the fatwa. After nearly a decade in hiding, protected 24/7 by British security, Rushdie emerged and moved to New York, thinking times had changed. But he was wrong.

Yet the author does not seem bitter or angry. “I think that’s who I am,” he said.

I suggested, “Most people would say, well, this is a clear recipe for a life with PTSD.”

“Well, I do have a therapist,” Rushdie said, “and I asked him at one point to list for me the symptoms of PTSD. And I said, ‘But I don’t seem to be having those symptoms, so what’s wrong with me?’ And he said, ‘Well, it’s because you’re a bad-ass, that’s the technical term.'”

The new book is the first fiction he’s published since the attack.

So, why “The Eleventh Hour”? “Well, for a start, I’m 78,” he said. “For another thing, I had a fairly intimate encounter with death, you know, and got away with it. But it makes you think, you know? So, I thought this idea of running out of time was something I had on the brain.”

“It’s a hard time in America”

“Now you have entered the magic space of my childhood,” the fictional narrator of one story says, as he takes a last walk up the hill to the neighborhood where the real Salman Rushdie grew up, in Mumbai, India (which he still calls Bombay). “My relationship with the place is kind of elegiac now,” Rushdie said. It’s a relationship about something that has passed.

He left India for an English boarding school at the age of 13. He left Britain after nearly 40 years there. He became an American citizen in 2016. Rushdie sees his place in the world through the eye of an immigrant.

Asked what he felt after becoming a U.S. citizen, Rushdie said, “I remember getting into a cab, leaving the office where I’d been sworn in, and being driven back through the streets of the city, and it felt different. I thought, Oh, I can belong. And it felt very good.”

I asked, “Did the feeling that you had when you were sworn in as a citizen become fractured or altered based on what’s happened since, both in public life in the United States, and to you?”

“It’s a hard time in America, but it’s a hard time all over,” he replied. “If you think of countries as people, there is their better self and their less-good self. And it would be nice if this country were to remember its better self.”

Random House

“The Eleventh Hour” includes a ghost story, characters who get even, a writer who disappears. But the book is also political. He writes: “Words such as good and bad or right and wrong are losing their effect, emptying of meaning, and failing anymore to shape society.”

The meaning of words matters to Rushdie, who has spent his entire career advocating for free speech, even though exercising it nearly got him killed.

He said, “The final story in the collection, ‘The Old Man in the Piazza,’ is kind of an allegory of that. In fact, free speech, to my great surprise, language itself, turned into a character, a female character. She just walked into the story and sat down in a corner, and I hadn’t expected her at all.”

“She is in fact a very old language, one of the oldest and richest…” he writes, in a story about what happens when speech is restricted. “It’s even possible, though it’s hard for her to admit this, even to herself, that she may die. Nobody’s listening. Nobody cares.”

Language abandons her corner, leaving people no longer able to speak: “We are at a loss to know how things will proceed. Our words fail us.”

“That’s pretty startling and scary,” I said.

“Yeah,” Rushdie agreed. “It’s supposed to be.”

READ AN EXCERPT: “The Eleventh Hour” by Salman Rushdie

WEB EXCLUSIVE: Watch an extended interview with Salman Rushdie (Video)

For more info:

Story produced by Amol Mhatre. Editor Jason Schmidt.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/salman-rushdie-on-the-eleventh-hour-and-free-speech/