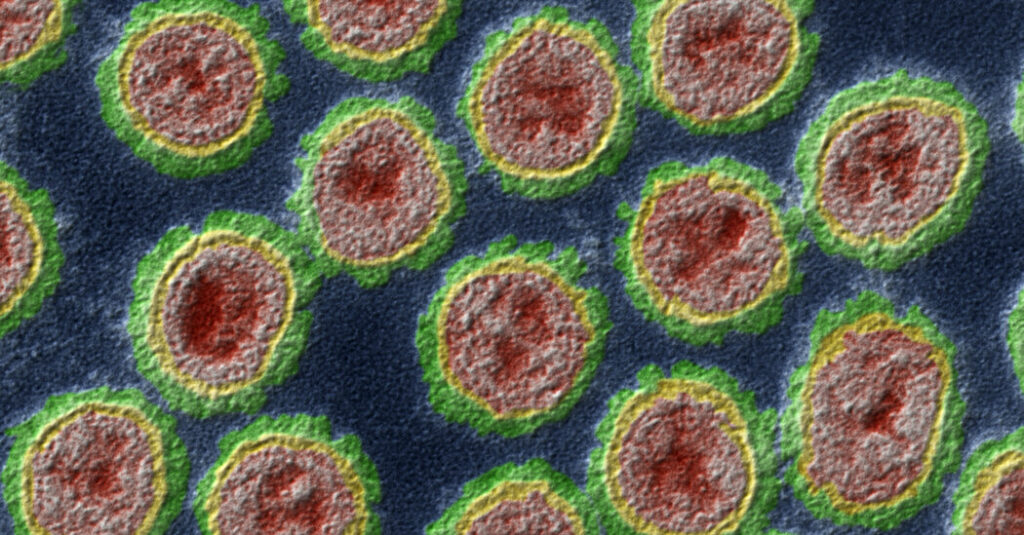

The bird flu virus sweeping across dairy farms in multiple states has acquired dozens of new mutations, including some that may make it more adept at spreading between species and less susceptible to antiviral drugs, according to a new study.

None of the mutations is a cause for alarm on its own. But they underscore the possibility that as the outbreak continues, the virus may evolve in ways that would allow it to spread easily between people, experts said.

“Flu mutates all the time — it’s what, sort of, flu does,” said Richard Webby, an influenza expert at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, who was not involved in the work.

“The real key would be if we start to see some of these mutations getting more prevalent,” Dr. Webby said. “That would raise the risk level.”

The virus, called H5N1, has infected cows in at least 36 herds in nine states, raising fears that milk could be infectious — concerns now largely put to rest — and highlighting the risk that many viruses might jump across species on crowded farms.

The study was posted online on Wednesday and has not been peer reviewed. It is among the first to provide details of a Department of Agriculture investigation that has been mostly opaque until now, frustrating experts outside the government.

The outbreak most likely began about four months before it was confirmed in late March, and spread undetected through cows that had no visible symptoms, the researchers found. That timing is consistent with estimates from genetic analyses by other scientists.

The virus has been detected in some dairy herds with no known links to affected farms, the authors said, supporting the idea of transmission from cows without symptoms and suggesting there may be infected herds that have not yet been identified.

The widespread nature of the outbreak also suggests efficient spread among the cows, according to the new paper. That may pose significant risks to the people who interact closely with those animals,

“The fact that this has been transmitting in cows for a while is definitely concerning,” said Louise Moncla, an evolutionary biologist who studies avian influenza at the University of Pennsylvania and was not involved in the work.

“I’m very much worried about making sure that we find cases in people,” she said.

In the new study, the researchers collected samples containing virus from 26 dairy farms in eight states. Cows are not typically susceptible to this type of influenza, but H5N1 appears to have acquired mutations in late 2023 that allowed it to jump from wild birds to cattle in the Texas Panhandle, the researchers said.

The virus then appears to have spread on dairy farms from Texas to Kansas, Michigan and New Mexico. In at least a dozen instances since then, H5N1 has also spilled from cows back into wild birds, and into poultry, domestic cats and a raccoon.

The findings should prompt large-scale surveillance not just of affected farms but also those without reported infections, said Dr. Diego Diel, a virologist at Cornell and an author of the study.

Many of the other species were probably infected after coming into contact with contaminated milk, which can contain very high levels of the virus, Dr. Diel said. A separate study published earlier this week reported that about a dozen cats that were fed raw milk had died.

It is not uncommon for dairies to dump discarded milk into manure pits or lagoons. That “could definitely serve as a source of infection to other susceptible species,” he said.

Researchers are closely monitoring H5N1 genetic sequences from cows for mutations that would allow the virus to infect or spread among mammals, including humans, more easily.

The only person to have been diagnosed with bird flu during the current outbreak carried a virus with a mutation that allowed it to infect people more efficiently. One cow in the study also carried H5N1 with that mutation. More than 200 others were infected with versions of the virus bearing a different mutation that offers the same advantage.

Veterinarians began observing unexplained drops in milk production in cows in late January and sent samples in for testing. The Department of Agriculture did not confirm infections until March 25.

“The more widespread H5N1 becomes, the more chance there is that it could hit upon a combination of mutations that could increase its risk to humans,” said Jesse Bloom, an evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle.

“On the other hand, H5N1 has been circulating in various species and causing added human infections for over two decades, and so far we haven’t had a pandemic,” he said. “It’s one of those situations where it could happen next week, but it also could never happen.”