Nairobi, Kenya – On June 7, Albert Ojwang was visiting his parents in his home village of Kakoth in Kenya’s Homa Bay County. His mother had just served him ugali (maize meal) and sukuma wiki (kale) for lunch when police officers on motorbikes arrived at the family’s compound.

Before Ojwang could take a first bite, they arrested him, taking him to the local Mawego police station before transporting him 350km (200 miles) to the Central Police Station in the capital, Nairobi.

The officers told his parents he had committed an abuse against a senior government official and was being arrested for publishing “false information” about the man on social media.

Ojwang, a blogger and teacher, had no criminal record and was just a month shy of his 31st birthday. But it was a celebration he would not live to see because less than a day later he was dead.

Police said he died by suicide after “hitting his head” against the wall of a cell where he was being held alone. But after an uproar from the public and rights groups and further investigation, the claim did not hold up. Eventually, two police officers were arrested.

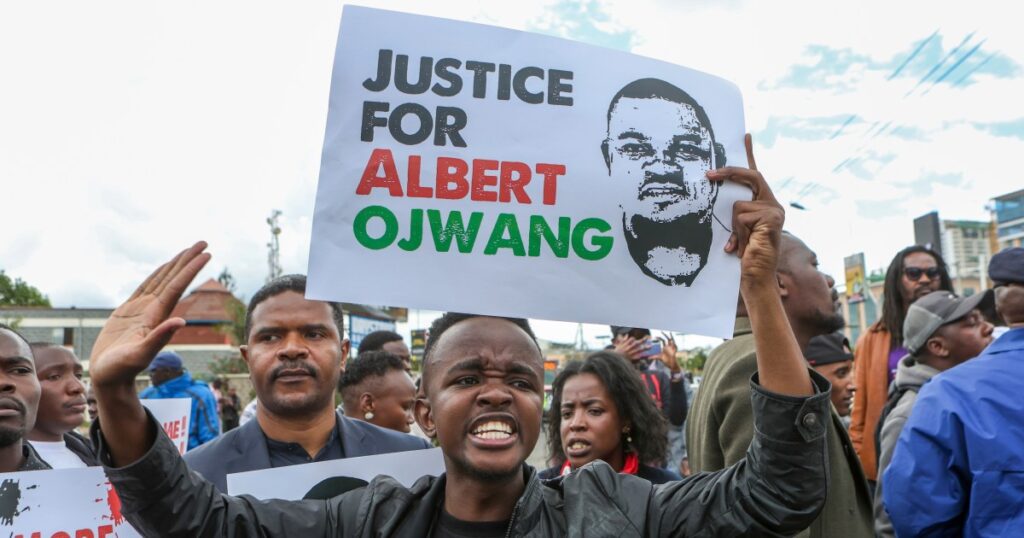

Still, the public anger that erupted after Ojwang’s death did not abate.

Kenyans have been on tenterhooks since mass antigovernment protests erupted across the country a year ago – first against tax increases in a finance bill and later for the resignation of President William Ruto.

In the time since, police have been accused of human rights abuses, including allegations of government critics and activists being abducted and tortured.

Ojwang was seen by many as yet another victim of a system trying to silence those attempting to hold the government to account.

And in the month since his death, angry protests have soared; state violence – and deaths – against civilians have continued; and young people seem determined not to give in.

‘False and malicious information’

Ojwang was the only child of Eucabeth Ojwang and Meshack Opiyo, a retired quarry worker who had endured hard labour for 20 years in Kilifi County to send his son to school.

Opiyo left the back-breaking job after Albert Ojwang had secured a job as a teacher, hoping his son would help take care of the family after earning a degree in education.

“I had only one child. There’s no daughter. There’s no other son after him,” he told Al Jazeera. “I have suffered … while [working] in a quarry in Timbo for 20 years so that my child could go through school and earn a degree,” he added, saying Ojwang left behind a three-year-old son.

Ojwang was a promising teacher at Kituma Boys’ Secondary School in the coastal Taita Taveta County, about 700km (435 miles) southeast of his childhood home, his family said.

Media reports said he was linked to an account on X that several people used to publish news about Kenya’s government and politics. That’s what drew the attention of the authorities who came to his father’s house that June afternoon.

That day, the arresting officers assured Opiyo his son would be safe when they took him into custody. Overnight, the father left for Nairobi – taking his land title deed with him to use as a surety to bail his son out because he had no other money. But the news he received was of his son’s death.

“I thought we would come and solve this issue. I even have a title deed here in my pocket that I had armed myself with, so that if there were going to be need for bail, we would talk with a lawyer to bail him,” Opiyo told journalists the Sunday morning after his son’s death, having just learned what had happened to him.

Despite police claims that Ojwang died from self-inflicted injuries, his family and the public were sceptical. Human rights advocates and social media users alleged foul play and an official cover-up by police.

As public pressure mounted on the police to offer clarity, Inspector General of Police Douglas Kanja confirmed that his deputy, Eliud Lagat, was the senior official who had made a “formal complaint” that led to Ojwang’s arrest.

“The complaint alleged that false and malicious information had been published against him [Lagat] in the X – that is, formerly Twitter – social media platform. The post claimed that he was involved in corruption within the National Police Service,” Kanja said before Kenya’s Senate and the media on June 11.

At first, Kanja repeated to the media that Ojwang had hit his head on the wall, killing himself in the process. But when questioned by lawmakers in the Senate, he admitted that was incorrect.

“Going by the report that we have gotten from IPOA [Independent Policing Oversight Authority], it is not true; he did not hit his head against the wall,” Kanja said. “I tender my apology on behalf of the National Police Service because of that information.”

A team of five government pathologists also released a report that revealed severe head injuries, neck compression and multiple soft tissue traumas. The cause of Ojwang’s death, they determined, was a result of the injuries, not a self-inflicted incident.

Meanwhile, Ann Wanjiku, the IPOA vice chairperson, told senators that preliminary findings showed Ojwang was alone in the cell but two witnesses who were in the next cell said they heard loud screams from where Ojwang was held.

The IPOA report also suggested there was foul play at the Nairobi Police Station because CCTV cameras had been tampered with on Sunday morning after Ojwang’s death.

Subsequently, several people were arrested and investigated, including two police officers who have been charged.

Police Constable James Mukhwana, an officer arrested and arraigned in court over Ojwang’s death, told IPOA investigators that he had acted on orders of his boss.

“It is an order from the boss. You cannot decline an order from your superior. If you refuse, something may happen to you,” he said in a statement to the IPOA. He added that his superior told him: “I want you to go to the cell and look at those who have been in remand for long. Tell them there is work I want them to do. There is a prisoner being brought in. Take care of him.”

Mukhwana pleaded not guilty in court but said he was sorry about the death in his statement, adding: “Ojwang was not meant to be killed but to be disciplined as per instruction.”

Who is ‘sanctioning’ these killings?

Since Ojwang’s death, Kenyan rights organisations have condemned what they say is his “murder”, calling the failure by authorities to hold accountable those responsible for police brutality as disrespect for human rights.

“The savage beating to death of Albert Ojwang and the subsequent attempts to cover this up shatter once more the reputation of the leadership of the Kenyan Police Service,” Irungu Houghton, the executive director at Amnesty International Kenya, told Al Jazeera.

“Amnesty International Kenya believes the failure to hold officers and their commanders accountable for two successive years of police brutality has bred the current impunity and disrespect for human rights,” he said.

Houghton also called for all those implicated to step aside and allow for investigations to take place.

“To restore public confidence and trust, all officers implicated must be arrested. … Investigations must be fair, thorough and swift. This moment demands no less.”

Amnesty has previously called out police abuses, including “excessive force and violence during protests”, and reported abductions of civilians by security forces. Rights groups said more than 90 people have been forcibly disappeared since June 2024.

“Albert Ojwang’s killing in a police station comes after persistent repeated police denials that the normal chain of police command is not responsible for the 65 deaths and 90-plus enforced disappearances seen in 2024,” Houghton said.

“Who are the officers abducting and killing those who criticise the state? Who is sanctioning or instructing these officers? Why has the government found it so difficult to trigger deep reforms to protect rather than stifle Kenyans’ constitutional freedom of speech and assembly as well as act on public policy opinion?” he asked.

Speaking in an interview with Kenya’s TV47 on June 24, the National Police Service Spokesperson Michael Muchiri acknowledged police brutality within the service, saying it was wrong.

“We accept and we acknowledge that within our ranks, we’ve gotten it wrong multiple times,” he said. But he added: “An act by one of us, and there have been a couple of them many times over, should not in any way be a reflection of the whole organisation.”

Al Jazeera reached out to Deputy Inspector General of Police Lagat to comment on the allegations against him, but he did not respond.

Shot at protests

Many of the Kenyans reportedly targeted by police and other “state agents” were young, vocal participants in the antigovernment protests that engulfed the capital and other cities last year.

After Ojwang’s death, the Gen Z protesters once again erupted in anger.

On June 17, they staged a demonstration in Nairobi to demand justice for their fallen comrade. Things soon got out of hand as the police used force, resulting in fatalities among the young people.

Boniface Kariuki, a mask vendor in Nairobi, was caught between the police and protesters, and the police fired a rubber bullet at his head at close range, sending him to an intensive care unit at the Kenyatta National Hospital. He was declared brain dead after a few days and died on June 30.

An autopsy report released on Thursday said Kariuki “died from severe head injuries caused by a single close-range gunshot”. It further revealed that four bullet fragments remained lodged in his brain.

Two officers who had been caught on camera firing the deadly bullet have been charged.

This came about the time Kenyan youth also marked a year since the antigovernment protests began on June 25, 2024.

In line with the anniversary, many young people across the country took to the streets to express their anger against the government.

Those protests also became violent. Many businesses were destroyed in Nairobi, and some police stations in other places were set ablaze.

That same day, three 17-year-olds, among others, were shot dead in different parts of the country. While the police have not commented on the deaths, the victims’ families and rights groups say all three were killed in crossfire during the protests.

Dennis Njuguna, a student in his final year of secondary school, was shot in Molo, Nakuru County, as he headed home from school for his mid-term break.

In Nairobi’s Roysambu area on the Thika Superhighway, police reportedly also shot dead Elijah Muthoka, whose mother said he had gone to a tailor but did not come back. That evening, she would receive the news that he was hospitalised at the nearby Uhai Neema Hospital. He was then transferred to the Kenyatta National Hospital and pronounced dead the next morning.

Outside Nairobi in Olkalou, Nyandarua County, Brian Ndung’u was shot twice in the head, according to an autopsy report released by pathologists at the JM Kariuki County Referral Hospital. Margaret Gichuki, Ndung’u’s sister, said her brother had just completed his secondary school education and learned photography so he could help raise his college fees together with their mother, who is a daily wage labourer.

“He had gone out to do street photography, which was his passion, and that is where he got shot. I was home and learned about his shooting through Facebook images that were shared by friends,” Gichuki told Al Jazeera.

Gichuki described her brother as a hardworking young man who had a lot of dreams, but which were cut short by the bullet. “After the autopsy, we could not get further information about the identity of the bullet that was removed from his head, as the police took it,” she said, explaining that one bullet was fragmented in his brain while another was removed by doctors and handed to the police during autopsy.

Together with their cousin Margaret Wanjiku, Gichuki then called to inform their mother that Ndung’u was missing – not wanting to immediately shock her with the news that her son had died.

“Ndung’u had been pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital, but this was news that carried weight for [our mother], and we wanted to have her come home before we could break it other than tell her over the phone,” Wanjiku said.

‘Surge’ in harassment

Less than two weeks after that, Kenyans again took to the streets in demonstrations that once again turned deadly.

On Monday, they rallied for “Saba Saba” meaning “Seven Seven” in Kiswahili to mark the date on July 7, 1990, when people demanded a return to multiparty democracy after years of rule by then-President Daniel arap Moi.

This year, the protest turned into a wider call for Ruto to resign and also a moment to remember Ojwang.

Four days earlier, Ojwang’s body had arrived at his home in Homa Bay for a nighttime vigil before his burial the next day.

When it arrived, angry youth took hold of the coffin and marched with it to the Mawego police station, where he was last seen alive before he was taken to Nairobi.

At the station, the youth set the station ablaze before making their way back to Ojwang’s home with his body.

The next day at the funeral, Anna Ngumi, a friend of Ojwang’s, told mourners: “We are not going to rest. We are not going to rest until justice is done. Remember we are still celebrating Seven Seven here. We will do Seven Seven for Albert Ojwang.”

But at the rallies, police were once again heavy-handed. In Nairobi, they fired live rounds and water cannon at the protesters. Eleven people were killed.

The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights said people were also abducted and arrested, adding that it was “deeply concerned by the recent surge in harassment and persecution of Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) accused of organizing the ongoing protests”.

‘Why did you kill my child?’

Within his circles, Ojwang is said to have been a humble person who never quarrelled with anyone and instead sought peace whenever there was a conflict.

His university friend Daniel Mushwahili said Ojwang was modest and sociable.

“I knew this person as a very cool and outgoing person. He had many friends. … He was not an arrogant person, not a bully, and did not even participate in harassing anybody,” Mushwahili said. He was “a person who seeks peace”.

Ojwang’s mother Eucabeth, speaking at a reception by comedian Eric Omondi, lamented her son’s killing, saying she had lost her only child and did not know how the family would cope without him.

“I had hope this child would assist me in building a house. He even had a project to plant vegetables, so we could sell and make money. Now I don’t know where to start without him,” she said.

“I feel a lot of pain because there are people who came home and took my son. … I feel a lot of pain because he is dead.”

Meanwhile, as the investigation into Ojwang’s death continues, his father says he misses his “trustworthy” son, who he relied on to take care of the family’s most valuable things, even with the little they had.

Opiyo said that when the officers came to their house to arrest his son, they saw how little the family had and knew they would not fight back. In his grief, he said he now wants answers from the police and in particular Deputy Inspector General Lagat, who made the complaint against Ojwang.

“Today, my son is dead from injuries inflicted through beating. I need you to explain to me why you killed my child,” Opiyo said.

“My son did not die in an accident or in war. He died in silence in the hands of those who were supposed to protect him.”

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2025/7/9/killed-by-those-meant-to-protect-kenyans-outraged-by-police-violence?traffic_source=rss