As Lehman Brothers hurtled towards bankruptcy in September 2008, the executives at the world’s largest derivatives exchange found themselves in a race against time: find a new home for the failed bank’s trading book or face more cascading chaos.

In an early harbinger of a new era for markets, the winner of the bidding war for Lehman’s bets on currencies, agricultural commodities and interest rates was not one of Wall Street’s big banks, but a secretive Chicago trading firm called DRW whose founder exuded a quiet but unshakeable confidence.

“Call me any time, any day or night, I will give you a price on whatever portfolio you want,” Don Wilson told a senior CME executive multiple times ahead of the crisis.

Wilson’s willingness to take on positions worth hundreds of millions of dollars as crisis-ridden markets gyrated would come to embody the ascent of a breed of younger, privately held trading firms which first challenged Wall Street’s bulge bracket — and then surpassed it.

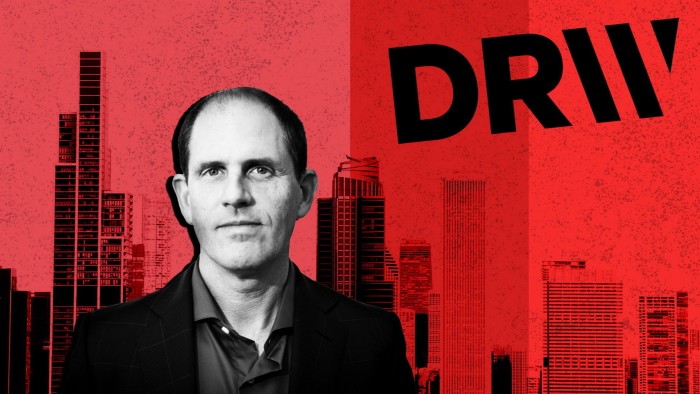

As banks have found their risk-taking abilities hamstrung by ever-greater regulation, Wilson has built one of the world’s largest trading firms by headcount behind Susquehanna and Jane Street. From its founding in 1992, DRW now has about 2,100 staff trading across bonds, commodities, equities, derivatives and cryptocurrencies.

In the process the 56-year-old billionaire’s sharp trading instincts have become revered within Chicago’s boisterous futures world; his intense competitive spirit underlined by his success as a catamaran sailing champion.

Wilson’s career mirrors the trends that have reshaped trading over the past four decades, from the 1980s ‘open outcry’ pits of Chicago, to electronic trading in the 1990s as telecoms and computing networks exploded, to outcompeting big banks with algorithms that could trade market events in microseconds compared to the seconds it took for rivals.

“Markets are Darwinian,” Wilson told the Financial Times in an interview. “They constantly become more efficient and if you can’t evolve at a rate that is at least equal to the market then you become irrelevant.”

As the founder and controlling shareholder of DRW — named for his initials — Wilson wields enormous influence in markets, unburdened by the constraints of shareholders or investors.

Part of DRW’s business involves liquidity provision, where it executes large block trades with counterparties who want to take a market position without moving market prices.

But the biggest component of its revenues is from directional bets, taking on positions where it thinks it has understood the market mechanics and risks better than others. More than half of its income comes from fundamental bets on the markets.

That makes it more akin to a hedge fund or a highly sophisticated family office such as Michael Platt’s BlueCrest Capital Management. But Wilson also retains a controlling stake, unlike rival firms such as Jane Street.

That gives him freedom from the demands of outside investors who may demand their money back in times of stress.

“If there is a bad quarter, no one is pulling money out of DRW,” said the head of a rival Chicago trading firm.

Wilson has used this flexibility to take opportunistic bets — not all of which have been smooth sailing. Wagers on property in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and on Bitcoin were savvy; ventures to tokenise property and apply blockchain technology to financial markets have yet to pay off.

Now he sees potential in trading graphics processing unit (GPU) power, the fuel of the artificial intelligence boom.

“DRW is different, it’s Don’s shop; he’s the guy that sits in the room and makes things happen,” said one executive at a large exchange who knows Wilson.

Wilson’s training for his trading career started with a family card game. He grew up playing a fast-paced version of competitive solitaire called “pounce”, with players frantically racing to place their cards on an eligible deck across the table before their opponents.

“You have to take in a tremendous amount of information and make risk-reward decisions on how to allocate your focus because you can’t possibly take it all in,” Wilson said. “[It was] great training for the trading pit.”

Wilson landed his first job in the pit as a University of Chicago graduate in 1989, with the trading firm Letco. At the time, the trading culture in Chicago was such that firms would take a punt on talented college graduates, granting them a small allocation of capital to see how they fared — $100,000 in Wilson’s case. Like the multi-manager hedge funds of today, success would be rewarded with more capital and failure could mean a swift exit.

New titans of Wall Street — an FT series

This is the last in a series on the secretive trading giants that now dominate a key part of Wall Street.

The first instalment told the story of how the big banks, hamstrung by regulation, lost a technology arms race — and their trading superiority.

The second covered Jane Street and how it rode the ETF wave to ‘obscene’ riches.

Third was XTX: the London-based firm through which the Russian-born billionaire Alex Gerko conquered the foreign exchange market.

The fourth explained how Jeff Yass’s obsession with odds spawned Susquehanna — and shaped the industry’s approach to markets.

The fifth looked at hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin’s money machine: Citadel Securities.

Find all the articles here

A few weeks after Letco allocated him his capital to trade, Wilson took a big bet that eurodollar futures would fall — only for a unexpected stock crash to send the prices soaring and landing Wilson with a loss of about $30,000.

“I was sick to my stomach, it was just so scary,” he said. “There are a lot of people who start off and have a good run and then their heads get really big . . . That event certainly made sure that it didn’t happen [to me].”

He recalls how he loved the chaos of the CME trading pits, where traders in brightly-coloured jackets used a combination of shouting and hand signals to communicate prices and quantities they wanted to buy and sell.

But he suspected it was only a matter of time before electronic trading took off, with blinking screens and humming server rooms hosting the drama of market rallies and crashes. In 1992 Wilson set up his own firm, DRW, hiring people with a quantitative background, software developers and “kids out of college” to become traders.

“Don Wilson and Ken Griffin were the Steve Jobs-type brilliant people who could see the future,” the head of the rival trading firm said.

DRW started off as an interest rate derivative specialist, stemming from Wilson’s expertise in the eurodollar option trading pit, gradually expanding to other asset classes including foreign exchange and physical commodities.

The firm now operates in every major asset class and is one of the world’s biggest derivatives traders: over the past 12 months DRW says it accounted for 29 per cent of options and 13 per cent of futures volumes on NYSE parent company Intercontinental Exchange, and 12 per cent of options and 5 per cent of futures on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

Its revenue and profit figures are private. A single London-based subsidiary made almost $1bn in revenue over the course of 2017 and 2018, but stopped filing accounts after that date. A small subsidiary in Singapore with roughly 70 employees set up in 2017 brought in $312mn in net revenues last year, according to company accounts. A network of smaller subsidiaries of the Singapore branch in the Netherlands, Israel and India, had a net book value of $282mn, filings said.

Wilson has a controlling equity stake in the firm but has doled out equity to 15 partners. He said he has tried to engineer a “perpetual partnership structure” where big money makers and contributors to the firm’s success are rewarded with equity.

“The goal is to create a kind of ongoing renewable living, breathing organism,” he said.

But Wilson has used the flexibility of his private ownership to take risky bets on assets that other large trading firms have avoided, including property and cryptocurrency.

He even launched a real estate arm called Convexity in the wake of the financial crisis — its name a reference to the mathematical relationship between interest rates and bond prices, and one it shares with Wilson’s catamaran racing team.

That diversification has had its downsides, with the property portfolio dragging down DRW’s credit outlook with rating agencies Moody’s and S&P.

His bet on Bitcoin proved more prescient, as a fragmented and nascent ecosystem meant there were enormous price discrepancies between exchanges for years, something DRW could take advantage of.

Wilson discussed a potential investment in the cryptocurrency with staff as early as 2012, calculating there was a 10 per cent to 20 per cent chance “the majority of the world population” would agree Bitcoin was “digital gold”. With Bitcoin’s price then around $12 or $13, they were good enough odds.

He launched cryptocurrency trading firm Cumberland in 2014, then doubled down on the bet in the years that followed, winning 70,000 Bitcoin in US government auctions of holdings seized from the online illegal drug market Silk Road. Now that stash would be worth about $5bn.

“These guys made crazy money because the spreads were huge . . . they were arbitraging all day long,” said one former broking executive at a large bank that worked with DRW.

DRW said it did not comment on specific trades or assets it held.

In his efforts to stay ahead of his competitors, Wilson has sailed close to the wind, attracting unwanted attention from regulators.

In 2013, the US derivatives regulator, then helmed by Gary Gensler, who is now chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, sued Wilson and his firm for allegedly manipulating the price of an interest rate futures contract. Unlike most firms, Wilson refused to settle and took the regulator in court.

DRW won a decisive victory in 2018, with a judge ruling Wilson’s trading strategy was based on a “superior knowledge” of the market rather than manipulation.

“It is not illegal to be smarter than your counterparties in a swap transaction, nor is it improper to understand a financial product better than the people who invented that product,” the judge said at the time.

Last month, Gensler came for round two, charging Cumberland DRW with operating as an unregistered securities dealer because it sold more than $2bn worth of cryptocurrencies that the SEC argues are under its jurisdiction.

Cumberland said it will fight the case, and said it tried in good faith to operate a registered business but was told by the SEC in 2019 that it could not use its broker-dealer to trade the cryptocurrencies referred to in the regulator’s complaint.

“We have proven before our firm’s willingness to defend ourselves against overzealous regulators wielding their power in ways that harm rather than benefit the market,” Cumberland said. “We’re ready to defend ourselves again.”

Gensler’s SEC has adopted new rules to more closely regulate trading firms such as DRW and hedge funds, broadly arguing that as these groups become more powerful players in the market, they should come under closer supervision of the regulator.

Wilson argues instead that piling additional regulations on to the sector would hamper its ability to provide liquidity during market panics.

“It’s funny, regulators were concerned that deposit-taking institutions were taking too much risk and they wanted them to take less risk [after the financial crisis],” he said. “So you would think that when private organisations wind up picking up the slack then that would be a good thing.”

With the return of Donald Trump to the US presidency, DRW and its ilk may be granted a reprieve. Financial services executives are expecting deregulation and a more permissive approach under him and a Republican-controlled Senate.

Wilson says he largely lets his partners and their teams get on with their jobs, only becoming deeply involved across the firm during periods of heightened volatility such as during the Covid-19 pandemic. He spends much of his time thinking about the next big opportunity, especially in technology, saying he enjoys thinking about the “new, new thing”.

That next opportunity could be tied to the chip boom which is powering the rise of the huge AI models behind software such as ChatGPT. Wilson is investigating ways to potentially trade the asset — processing power or compute — which he said could become the world’s biggest commodity.

“I had this thesis that total dollars spent on compute will exceed total dollars per year spent on crude oil in the next 10 years,” he said. “Does that mean that compute becomes the largest commodity in the world? I think that it’s a reasonable argument.”

https://www.ft.com/content/4001099b-12a9-4a3f-bf21-7333e88b536d