The third scene of the new Broadway production of “Eureka Day” could be titled The Way We Discourse Now. As written by the playwright Jonathan Spector, the scene reliably has audiences laughing so loudly that the actors are drowned out.

The situation is this: It is 2018. The principal of the progressive private school Eureka Day in Berkeley, Calif., and the four members of its executive committee must inform the other parents that a student has mumps, and therefore by law any students who have not been vaccinated must stay home to avoid exposure. (Vaccine skepticism was not uncommon in this milieu, particularly pre-pandemic.)

The school leaders, an optimistic bunch dedicated to diversity and inclusion, hold a town hall-style meeting “to see,” says the principal, Don, “how we can come together as a community and exchange ideas around a difficult issue.”

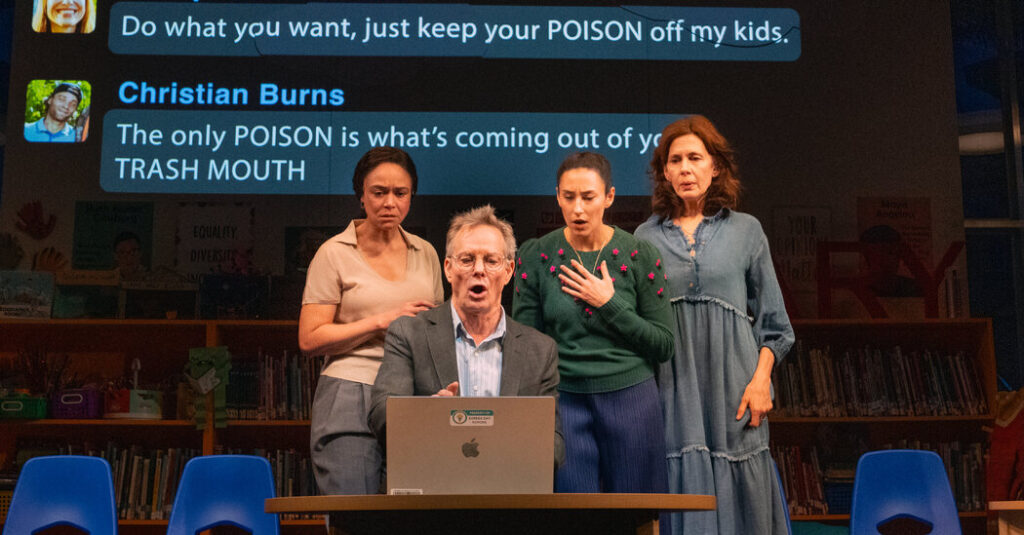

At the meeting, which is being held remotely, Don speaks while sitting in front of a laptop in the school library, addressing parents on a Zoom-like video app. The executive committee members are behind him. The rest of the school’s parents weigh in on a chat-like function. Their messages — 144 of them — are projected above the actors for the audience to read.

The online conversation quickly descends into vicious attacks. “Typical behavior from the Executive Committee of FASCISM.” “Sorry, chiropractors are not doctors.” “That’s child abuse!!!”

“The scroll of their projected comments (“Were you dropped on your head as a child?”) is the exposed id of a community that professes perfect consideration of differing opinions but is actually a hotbed of intolerance,” Jesse Green, chief theater critic for The New York Times, wrote in his review of the play.

Each comment is assigned to one of dozens of parents — each with their own names and avatars — and cued to specific moments in the script. The audience’s attention is invariably drawn to the projected comments. The result is something quite unusual — and uproariously funny.

In interviews, several artists involved in the play’s current Manhattan Theater Club production at the Samuel J. Friedman Theater and the first staging at Aurora Theater Company explained how this scene is staged, what makes it work and why a panicked Don (who is reading the comments) observes, “Iiiiiii am feeling like this format is not facilitating us all bringing our best selves to this conversation.” These are edited excerpts from our conversations.

“Eureka Day” debuted in 2018 in Berkeley, Calif., as an Aurora Theater Company commission.

JOSH COSTELLO (artistic director, Aurora Theater Company) This was pre-Covid. There were measles outbreaks happening because parents weren’t vaccinating their kids.

BILL IRWIN (Don, the principal) The play is set in, and in some ways the play is about, Berkeley, Calif. I used to do mime on Sproul Plaza. I know Berkeley and love Berkeley, in its foibles and deep integrity at the same time. And there is a kind of — I’m afraid to be condescending here, but with a cold eye — ethos there that the play is a portrait of.

JONATHAN SPECTOR (playwright) When I was researching the play, I spent a lot of time in the depths of these internet message boards where people would argue about vaccines. And they’re just so nasty. Because so much of the way that we live our lives — certainly around an issue like that — is online, I felt like not to bring that element into the play would be leaving out a really important part of how we interact.

IRWIN These characters just love the notion of community and consensus. One of my favorite things lately in the show is anticipating, in Scene 2, the excitement about how great Scene 3 is going to be. This is pride going before a fall.

The production’s stage manager clicks into each chat message, posting each one at exact moments that the script cues to onstage lines. The messages appear above the actors, for the audience, and on the laptop screen that only the actor playing Don can read.

SPECTOR There’s no way to do it if that actor [playing Don] doesn’t have [the messages] in front of him, because at moments he’s a surrogate for the audience — his reaction to what’s happening is a big part of that scene.

NICKI HUNTER (associate artistic director, Manhattan Theater Club) For the first couple previews, we had to make sure we were amplifying Bill Irwin’s voice appropriately — the laughter was so robust backstage, they couldn’t hear the cues.

CHARLES M. TURNER III (production stage manager) I call the show off stage right. I have a speaker that gives me the feed through the stage mics. But the laughter overtakes that. So sometimes I am following along in the script to see, “Yes, Bill said that word,” or I’m waiting for a gesture from him. It’s never the same way twice — in a beautiful way. I know that’s probably scary for a director to hear.

ANNA D. SHAPIRO (director) What you’re trying to do is make sure the audience can relax into what they can’t hear, understand they’re not supposed to hear certain things, make them believe that they alone have grabbed certain other things — “Oh, did you hear that?” The goal is to make it joyful, accessible and true all at the same time.

TURNER Usually Bill will come off that scene and he’ll give me a salute or a thumbs up, or we’ll look at each other funny, or we’ll be like, “Wow, that audience.” There’s always a little check-in. Pretty much we check in about that scene every day.

As new actors and crew members come to the play, they are surprised by how the audience responds to the scene.

SPECTOR That first performance, I had comments basically running constantly through the scene with no breaks, and you couldn’t hear a word onstage because there was just so much laughter.

COSTELLO He had to go back and rewrite, and work on the timing of when each thing pops up, so that a few really important lines of dialogue could still be heard. He built in pauses. He made it less funny. It made it flow better and allowed a couple key lines of dialogue to land, so you could follow what was happening.

JESSICA HECHT (Suzanne, a parent on the executive committee) When we were in rehearsal, no one laughed. And I said, “The audience is going to feel like I have such a flimsy argument.” And Jonathan said: “No, I don’t think they are. I think they’re going to be laughing at the Zoom feed.” And I kept thinking, “God, he’s kind of full of himself!” Cut to the first preview, they’re screaming with laughter.

The four actors playing the parents act out an entire scene, with dialogue, knowing the audience is largely not hearing or paying much attention to them.

“EUREKA DAY” SCRIPT It is crucial that the actors do not hold for laughs coming from the Live Stream comments. The scene is built to allow many of the lines to be lost.

HECHT I have to stay in my lane. I am not the agent of that scene. Bill and Chuck [the production stage manager] have a dance worked out, and there’s very, very little left up to chance. I’d equate it to certain television shows where they have such a high level of comedy, and you wonder if there’s some brilliant improvisatory spirit among the actors, and the answer is: No, it’s being written and directed and acted within an inch of its life.

IRWIN Sometimes you have to think of yourself as foreground — an important part of the story, but an almost pantomimic scene of people talking, and thinking that what they’re talking about is the most important thing.

Among those who produce the scene, theories abound about just what exactly makes it tick.

SPECTOR Early on in Covid, I was constantly getting texted screenshots from friends on a Zoom for their kids’ school, like, “Oh my God, I’m in your play.”

IRWIN It’s Jonathan’s shrewd writing. He’s sort of a Berkeley Chekhov. Our illusions about where we sit and how important we are in the world.

SPECTOR If we’re actually in the room with another human being, there’s a limit to how nasty we will be. But when you’re online, that just goes away.

SHAPIRO The scene makes people feel seen, acknowledging at every level our experiences of the last couple years. It’s just been a horror show of no decorum. And whether that plays out on the larger scale — which it does — it plays out in a domestic scale as well, which is what happens when an essentially homogeneous group of people realizes that they don’t share every belief and thought.

SPECTOR [The audience’s following the chat] probably says an unfortunate amount about how our attention works with technology. But that is also the thematic idea of the scene: that whatever attempt at thoughtful discussion and collaboration that maybe can be productive in real life, once you put it online, it just becomes impossible.

COSTELLO The play feels more relevant than it did before the pandemic in some ways. When the right decided that there was political capital in denying the science of vaccinations, it changed that dynamic. The play is still about people on the left, but ultimately the play is not about vaccinations. The play is about, “How do you get along with people when you can’t agree on the facts?”

IRWIN I’m very wary — I would almost use the word loathe to talk about the scene, because of its delicate mystery.