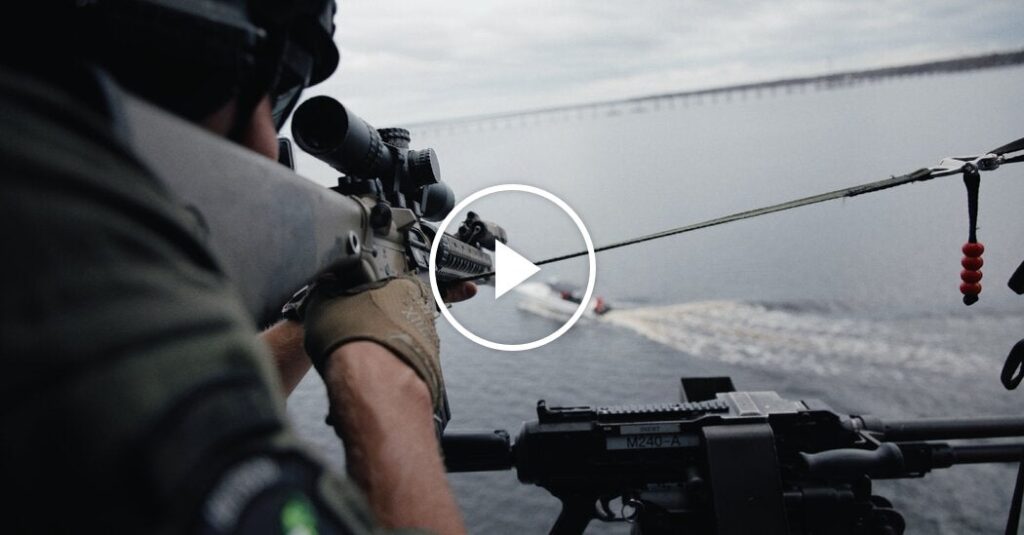

We’re outside of Jacksonville, Fla., flying with the Coast Guard’s Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron, or HITRON, as they chase down a speedboat simulating drug-runners at sea. These are the counterdrug cops of the high seas. They intercept suspicious boats, seize illegal narcotics and arrest suspected drug smugglers to try to bring them to justice. The gunner aims for the engines. “We don’t intentionally shoot to hurt, kill, injure anybody. Our primary target is going to be the engine.” Today, they’re practicing on a common smugglers’ tactic, using their bodies to shield the motors from gunfire. They do this because they know the Coast Guard will do what they can to avoid casualties. “And you’re taking extra caution not to hit any people on board these suspected drug boats.” “Correct.” “Why is that?” “I just joined a life-saving service. That’s really it.” The Pentagon has been striking the same type of speedboats the Coast Guard is targeting, declaring drug smugglers unlawful combatants in order to justify the operation. But legal experts have called the attacks a violation of U.S. and international law. We spent two days with HITRON and a tactical unit in Miami to see how they’ve been stopping and seizing drug boats by relying on nonlethal tactics long before the military got involved. For the past several months, the Coast Guard has focused its counterdrug efforts in the Eastern Pacific. Over 70 percent of cocaine destined for the U.S. is trafficked through here up to Mexico. “We’re formally classifying fentanyl as a weapon of mass destruction.” President Trump has cited fentanyl deaths to justify the lethal boat strikes. But boats that have been targeted were said to be carrying cocaine, not fentanyl. In early December, the Coast Guard seized a boat with 20,000 pounds of cocaine, one of its largest hauls ever. Two days later, in the same region, the U.S. military struck an alleged drug boat, killing everyone on board. I asked the Coast Guard about its mission and legal protocols to stop the boats, seize the drugs, and collect evidence that can be used to prosecute smugglers in court. “It’s the nature of law enforcement. No law enforcement officer ever goes into a scenario looking to throw restraint to the wind.” And they’ve had a record breaking year. The Coast Guard seized nearly $4 billion worth of narcotics, about four times their annual average, and detained 279 alleged drug traffickers. In a lounge above the hangar, Captain Broadhurst showed us videos of the methods his squad has honed over three decades at sea. “Has anyone ever successfully evaded a HITRON unit?” “We have a 97 percent success rate once we are on top of a vessel. So very few, I would say.” Broadhurst told us that smugglers also understand the Coast Guard’s limits and have adapted accordingly. In addition to throwing themselves on their engines, he showed us a video of suspected smugglers trying to thwart the Coast Guard by jumping overboard, knowing that they will shift strategy. “So at this point, we cease law enforcement, and we go into a search and rescue mode. As both a military service at the cutting edge of what we’re doing for the administration, and a life-saving service, there are just practical and humanitarian reasons why we have to get that person out of the water.” In October, President Trump, in justifying the boat strikes, said the Coast Guard interdictions had failed. “We’ve been doing that for 30 years, and it has been totally ineffective.” “How do you respond to that?” “The president does have a point that we’re patrolling somewhere twice the size of the United States of America, with fewer than 12 patrol cars. So you can understand that if we had more operational resources, we could be more operationally effective.” In Miami, we met a Coast Guard tactical team that boards the smuggling boats after the helicopter squad has disabled them. “All right, so your scenario: We have a vessel that we’re tasked with getting pos-con of and link up with the other team.” We watched them as they trained to board a much larger vessel, like a container ship or oil tanker. First, they enter the ship and quickly detain a crew member. Then on the next floor, they’re confronted by armed smugglers. As they are trained, they fire only in self-defense. It’s a scenario that could become more likely as the U.S. escalates tensions with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. In mid-December, President Trump declared a blockade on sanctioned oil tankers going to and from Venezuela. Since then, specialized Coast Guard teams operating off the coast of Venezuela have boarded and seized at least two oil tankers. With its unique authority to board stateless and illegal vessels at sea, the Coast Guard continues to play a critical role in enforcing the blockade.

https://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000010613888/us-coast-guard-drug-smuggling-boats.html