This is a patent application filed by a Chinese company in multiple countries to protect its novel design for an E.V. battery.

A single red rectangle with a patent drawing.

In 2000, Chinese applicants filed 18 clean energy patents that analysts said were internationally competitive.

18 red rectangles.

In 2022, Chinese applicants filed more than 5,000.

A grid of 5,206 red rectangles.

Over two decades China has leapt ahead of other countries, churning out innovative designs for the energy mix of the future: solar and wind power, batteries and electric cars.

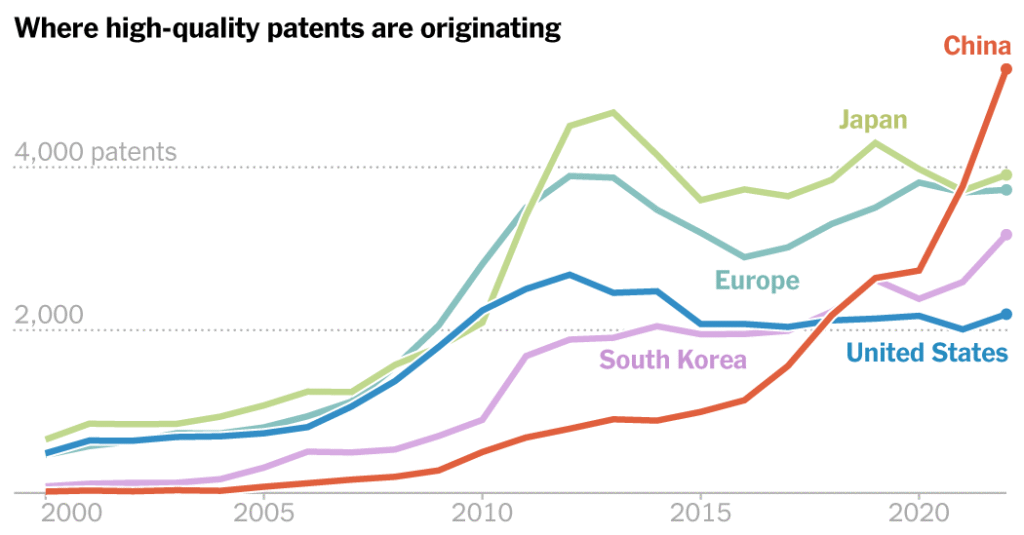

A line chart that spans the years 2000 to 2022, with lines in different colors showing the trends in annual high quality patent filings from China, Japan, Europe, Korea, and the United States.

Accused for years of copying the technologies of other countries, China now dominates the renewable energy landscape not just in terms of patent filings and research papers, but in what analysts say are major contributions that will help to move the world away from fossil fuels.

Where high-quality patents are originating

China leads in batteries and solar, while Europe still dominates wind energy and smart grids

“It may sound simplistic, but the ultimate indicator of patent quality is how much money a company or institution has spent on protecting its application, including by filing it in many countries,” said Yann Ménière, chief economist at the European Patent Office, which shared the most robust data available on trends in competitive patent filings with The New York Times. “Purely based on that, we can see how China has gone from being an imitator to an innovator.”

The European Patent Office data considers any application that has been filed in two or more countries to be high quality, based on the assumption that companies went through the trouble and expense of applying for a patent in more than one market with the intention of protecting their invention across borders. Patents prevent others from making, using or selling the innovation without permission for a specified period of time.

By that measure, China applied for more than twice as many high-quality clean energy patents as the United States in 2022, the most recent year of complete data. And while Chinese applicants continue to file a large number of lower-quality patents that may be duplicative or insignificantly different from existing inventions, a growing proportion are of higher quality.

That trend has been driven by strategic policies from Beijing as well as a maturing of China’s academic research environment.

“It is the opposite of an accident,” said Jenny Wong Leung, an analyst and data scientist at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, which created a database of global research on technologies that are critical to nations’ economic and military security, including clean energy.

Last summer, leaders of the Chinese Communist Party who gathered to plan the country’s future paid more attention to scientific training and education than any other policy except for measures to strengthen the party itself.

In mid-2015, the Chinese government announced a program called “Made in China 2025.” It would provide companies in 10 strategic industries with large, low-interest loans from state-owned investment funds and development banks, assistance in acquiring foreign competitors and generous subsidies for scientific research. At the time, the stated goal was that Chinese companies would control 80 percent of the domestic markets of those industries by 2025.

That effort has largely succeeded, Dr. Wong Leung and other analysts said.

Chinese clean tech companies have come to dominate both domestic and international markets. While Western countries like the United States and Australia pioneered now-widespread technologies like solar panels, batteries and supercapacitors (which are like batteries, only smaller, and provide quick bursts of energy), China is now building on those designs and creating new, groundbreaking versions.

“The sheer volume of Chinese investment has been so much larger than in the West,” Dr. Wong Leung said. “It meant they could build industries from the ground up, all the way through the supply chain.”

An inversion in clean energy research dominance

China is surging ahead in highly cited publications in global, peer-reviewed journals

But it hasn’t just been about money, analysts said. The Chinese government has encouraged cutthroat domestic competition that some economists have likened to “economic Darwinism.”

Sam Adham, head of battery materials at CRU Group, a market analysis company, described a typical scenario: First comes a flood of subsidies into a particular industry that the government has deemed strategic. Companies pile in, filing dozens or even hundreds of patents along the way. In the final stage, Mr. Adham said, the government pulls the subsidies and the less competitive companies essentially are “culled,” while “the remaining companies emerge stronger and they go overseas and take market share there.”

Take, for instance, batteries for electric vehicles. While the original breakthroughs in producing lithium-ion batteries were made in the United States three decades ago, further research received little government backing there. Meanwhile, Chinese companies grabbed the baton.

BYD, based in Shenzhen, recently surpassed Tesla as the world’s largest manufacturer of electric cars, and CATL, a Chinese rival based in Ningde, produces the most batteries. BYD and CATL have both relied on lithium-ion batteries that use relatively inexpensive iron and phosphate, combined with lithium, rather than nickel and cobalt, which Western producers have favored. Through patented breakthroughs, the Chinese companies made their batteries lighter, longer-lasting, faster to charge and cheaper to produce.

Those improvements are making electric cars safer and more convenient to drive, too.

A research team at CATL, which supplies batteries to electric automakers like Tesla and BMW, developed a way to minimize fire risk in car batteries that won a European Inventor Award in 2023. The series of patents, with unremarkable-sounding descriptions about battery covers and short circuits, amount to a major step forward in preventing catastrophic heat buildup and explosions when electric vehicles are overcharged.

Patents to make safer batteries

China has nearly 50 graduate programs focused on battery chemistry and metallurgy. According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 65.5 percent of widely cited technical papers on battery technology come from researchers in China, compared with 12 percent from the United States.

With its competitive advantage widening, China has sought to limit “technology leakage,” as some analysts put it. As of July, Beijing has restricted any effort to transfer out of China eight key technologies for manufacturing electric vehicle batteries, be that through trade, investment or technological cooperation.

“China has often done this unofficially in the past,” Mr. Adham said, “but now it’s becoming written law.”

That would very likely cement China’s dominant role in producing batteries unless other countries invest similarly in research. Analysts say those moves make the global energy transition, which is central to efforts to limit human-driven climate change, ever more reliant on Chinese technologies.

Biqing Yang, an analyst at Ember, a global energy research organization, created her own analysis of the European Patent Office’s data. “If you take China out of the data,” she said, “there are even recent years where you will find that global innovation has stagnated or even slowed down.”

And she said that recent announcements from the Chinese government indicated it was nudging companies to look beyond solar panels and batteries to more nascent technologies.

“Carbon capture, smart grids, the electrification of heavy industry, those are the frontiers,” Ms. Yang said.

Methodology

Patent data was provided by the European Patent Office, with each clean energy technology category based on either the Y02 tagging scheme or custom analysis done in part with the International Energy Agency. The count of patents is based on “international patent families,” which must be filed in at least two countries and excludes duplicative filings that cover the same invention.

Highly cited research data was provided by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, which uses publication data from the Web of Science Core Collection database. The underlying database includes peer-reviewed conference and journal publications and excludes book reviews, retracted publications and letters that were not deemed to reflect research advances.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/08/14/climate/china-clean-energy-patents.html