On July 1, 1970, one of the first independent abortion clinics in the country opened on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. New York State had just reformed its laws, allowing a woman to terminate her pregnancy in the first trimester — or at any point, if her life was at risk. All of a sudden, the state had the most liberal abortion laws in the country.

Women’s Services, as the clinic was first known, was overseen by an unusual team: Horace Hale Harvey III, a medical doctor with a Ph.D. in philosophy who, unbeknown to the clinic, had been performing illegal abortions in New Orleans; Barbara Pyle, a 23-year-old doctoral student in philosophy, who had been researching sex education and abortion practices in Europe; and an organization known as Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion, a group of rabbis and Protestant ministers who believed that women deserved access to safe and affordable abortions, and who had created a referral service to find and vet those who would provide them.

What distinguished Women’s Services — a nonprofit that first operated out of a series of offices on East 73rd Street and charged on a sliding scale, starting at $200 — was its counselors. They were not medical professionals, but regular women, many of whom had had abortions themselves. Their role was to shepherd patients through the abortion process, using a model of a pelvis to explain the procedure in detail, accompanying the women into the procedure room and sitting with them afterward. They also reported on the doctor’s performance. It was a model that other clinics would adopt in the months and years to come.

The clinic’s humane approach was in stark contrast to the attitude of many hospital personnel at the time, Jane Brody of The New York Times wrote in 1970. “Don’t make it too easy for the patient,” one administrator put it, summing up the hospital’s philosophy. “If it’s too easy, she’ll be back here in three months for another abortion.”

Women’s Services had some other unique features as well. The waiting areas were cheerfully decorated, with piped-in music, and the operating tables had stirrups cushioned with brightly colored pot holders, a flourish Dr. Harvey, who died on Feb. 14, had brought with him from his days working out of hotel rooms in New Orleans.

Unlike many illegal abortion providers in those pre-Roe v. Wade days, who made the process as bare-bones and speedy as possible in anticipation of a police raid, Dr. Harvey had not only softened the atmosphere of his New Orleans procedure room to make it less terrifying; he had also offered the women cookies and Coca-Cola afterward, to help them recuperate.

“Harvey’s conviction was that even a healthy patient would feel sick, in the face of a cold, sterile hospital environment,” Arlene Carmen and the Rev. Howard Moody, the leaders of Clergy Consultation Service, wrote in their 1973 book about the group, “Abortion Counseling and Social Change From Illegal Act to Medical Practice.” “Since abortion was not a sickness, the atmosphere associated with hospitals needed to be avoided.”

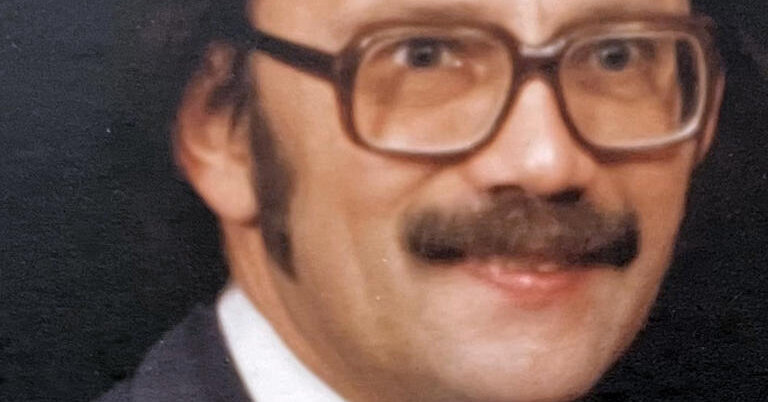

Dr. Harvey was 93 when he died at a hospital in the town of Dorchester, in England, after a fall, his daughter Kate Harvey, said. He had lived in England for many years.

Women’s Services opened with $15,000 in funding from Dr. Harvey. Ms. Pyle, who was the administrator, described in an interview the chaotic early days, as clients poured in from all over the country. The clinic operated from 8 a.m. to midnight, with personnel working two shifts. Ms. Pyle slept on a couch in the building. On average, she said, the clinic performed about 72 abortions a day.

Newspapers wrote glowing reports, singling out Dr. Harvey as an innovator. But after less than a year, Ms. Carmen and Mr. Moody, of the Clergy Consultation Service, discovered to their horror that Dr. Harvey had been operating without a medical license. He had surrendered it in 1969, after the Louisiana authorities learned that he was performing illegal abortions. He had to go, and quickly, before he jeopardized Women’s Services’ legal status.

Dr. Harvey had become an abortion provider to combat what he felt was an epidemic of unsafe abortions at a time when unmarried women were denied access to contraceptives, and when comprehensive sex education was discouraged. Low-income women suffered disproportionally.

As a teenager, raised as a conservative Christian, Dr. Harvey had gone through a period of soul-searching, concluding that he was an atheist. During the Vietnam War, he registered as a conscientious objector; instead of fighting, he worked as a health counselor at a Y.M.C.A. Later, in New Orleans, he set up an independent sex-education program, giving lectures, answering questions by telephone and handing out brochures on college campuses.

To Dr. Harvey, the importance of abortion was the idea of preventing “the loss of potential for women,” Ms. Harvey, his daughter, said. “It was a matter of principle to him.”

Horace Hale Harvey III was born on Dec. 7, 1931, in New Orleans into a once-prominent family that had developed what is known as the Harvey Canal, which became part of the Intracoastal Waterway in 1924. His father, Horace Hale Harvey Jr., was a gambler, and the family was poor; they moved around a lot as he tried various professions, including setting up a loan company. His mother, Florence (Krueger) Harvey, was a secretary.

Horace studied philosophy at Louisiana State University, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1955, and a medical degree there in 1966. In 1969, he received a master’s degree in public health and a Ph.D. in philosophy, both from Tulane University, in New Orleans.

Dr. Harvey moved to England after leaving the New York abortion clinic — a choice he made, his daughter said, because he approved of Britain’s National Health Service. He settled on the Isle of Wight, another considered choice: According to his research, it had the highest average temperature and received more hours of sunlight than anywhere else in England.

Dr. Harvey worked briefly in public health in his new country, advising on cervical cancer screening procedures, but spent most of his time researching aging — to prepare for his own old age — reading philosophy and attending to his duties as a landlord.

He had bought Puckaster Close, a rambling Victorian house, turning it into apartments that he renovated in a style as “quirky and characterful” as Dr. Harvey himself, his son, Russell, said.

In addition to his daughter and son, Dr. Harvey is survived by three grandchildren. His marriage to Helen Cox, a school headmistress, ended in divorce.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/25/health/horace-hale-harvey-dead.html