President Trump’s executive order freezing most U.S. foreign aid for 90 days has thrown into turmoil programs that fight starvation and deadly diseases, run clinical trials and seek to provide shelter for millions of displaced people across the globe.

The government’s lead agency for delivering humanitarian aid, the U.S. Agency for International Development, or U.S.A.I.D., has been hit the hardest. Mr. Trump has accused the agency of rampant corruption and fraud, without providing evidence.

The Trump administration ordered thousands of the agency’s workers to return to the United States from overseas; put all of the agency’s direct hires, including its roster of Foreign Service officers, on indefinite administrative leave; and shifted oversight of the agency to the State Department.

On Thursday, the Trump administration announced plans to gut the agency’s staff, reducing U.S.A.I.D.’s work force of more than 10,000 to perhaps a few hundred. On Friday, a judge temporarily blocked elements of the Trump administration’s plan to shut down the agency, though the aid freeze remains in effect.

How much foreign aid does the U.S. provide?

In total, the United States spent nearly $72 billion on foreign assistance in 2023, which includes spending by U.S.A.I.D., the State Department and programs managed by agencies like the Peace Corps.

As a percentage of its economic output, the United States — which has the world’s largest economy — gives much less in foreign aid than other developed countries.

U.S.A.I.D. spent about $38 billion on health services, disaster relief, anti-poverty efforts and other programs in fiscal year 2023. That was less than 1 percent of the federal budget.

Who are the recipients?

Mr. Trump’s freeze on U.S. foreign aid does not apply to weapons support for countries like Israel and Egypt, and emergency food assistance is also exempt.

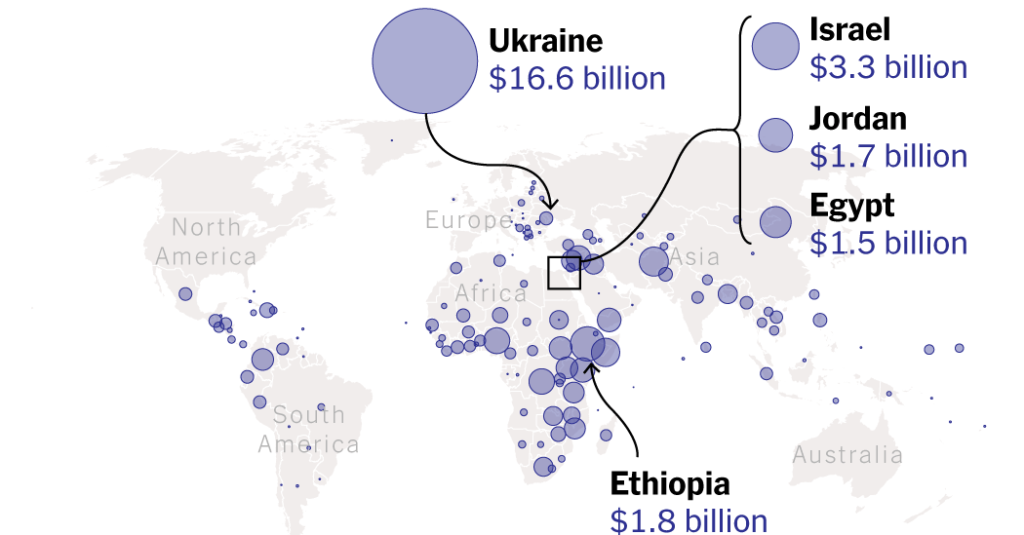

In 2023, the last year for which full data is available, Ukraine, which has been waging a war against Russia since Moscow’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, received $16.6 billion, the most U.S. assistance of any country or region. The bulk of that went to economic development, followed by humanitarian aid and security.

Israel — which was attacked by Hamas-led militants on Oct. 7, 2023, setting off a 16-month war in Gaza — received the second-highest amount of U.S. assistance: $3.3 billion in 2023, mainly for security.

Ethiopia, Somalia and Nigeria received more than $1 billion each in 2023, mostly for humanitarian aid.

In Latin America, Colombia was the top recipient of U.S. aid, $705 million, in 2023.

How is the money spent?

U.S. foreign aid can be structured as direct financial assistance to countries through nongovernmental organizations; military support; food and medical aid; or technical expertise.

Foreign aid can be a form of soft power, serving a country’s strategic interests, strengthening allies and helping to prevent conflicts.

In the case of U.S.A.I.D., money has gone toward humanitarian aid, development assistance and direct budget support in Ukraine, peace-building in Somalia, disease surveillance in Cambodia, vaccination programs in Nigeria, H.I.V. prevention in Uganda and maternal health assistance in Zambia. The agency has also helped to contain major outbreaks of Ebola.

Contrary to a claim by Mr. Trump, U.S. money has not been used to send condoms to Gaza for use by Hamas, health officials say. In a statement late last month, the International Medical Corps said that it had received more than $68 million from U.S.A.I.D. since October 2023 for its work in the enclave but that “no U.S. government funding was used to procure or distribute condoms.”

Instead, the group said, the money was used to operate two field hospitals, treat and diagnose malnutrition, deliver more than 5,000 babies and perform 11,000 surgeries.

Why was the freeze ordered?

For years, conservative critics have questioned the value of U.S. foreign aid programs. The Trump administration argues that the halt to foreign aid is necessary to examine whether U.S. funds are being wasted.

“Every dollar we spend, every program we fund and every policy we pursue must be justified with the answer to three simple questions,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in a recent statement. “Does it make America safer? Does it make America stronger? Does it make America more prosperous?”

On his Truth Social platform Friday, Mr. Trump wrote, “CLOSE IT DOWN!” He has asserted without evidence that the agency was “run by radical lunatics.”

Mr. Rubio, who previously spoke out in support of the agency, has taken aim at the organization, faulting its employees for “deciding that they’re somehow a global charity separate from the national interest.”

He has insisted, however, that the takeover was “not about getting rid of foreign aid.” He said during a recent Fox News interview, “We have rank insubordination” in the agency, adding that U.S.A.I.D. employees had been “completely uncooperative, so we had no choice but to take dramatic steps to bring this thing under control.”

What have been the effects of the aid freeze?

As organizations across the globe reeled, the Trump administration switched gears. Mr. Rubio announced that “lifesaving humanitarian assistance” could continue but that the reprieve would be “temporary.”

But by then, hundreds of senior officials and workers who help distribute American aid had already been fired or put on leave, and many aid efforts remain paralyzed.

Dozens of clinical trials in South Asia, Africa and Latin America have been suspended. The freeze left people with experimental drugs and medical products in their bodies, cut them off from the researchers monitoring them and spread fear.

In South Africa, for example, the freeze shut down a U.S.A.I.D.-funded study of silicone rings inserted in women to prevent pregnancy and H.IV. infection.

About 2.4 million anti-malaria bed nets, manufactured to fulfill U.S.-funded orders and bound for countries across sub-Saharan Africa, were stuck in production facilities in Asia. Those contracts are frozen because the U.S.A.I.D. subcontractor that bought them is not allowed to talk to the manufacturer under the terms of the freeze.

In Uganda, a national anti-malaria program suspended spraying insecticide into village homes and halted shipments of bed nets for distribution to pregnant women and young children.

And in Syria, the executive order threatens a U.S. program supporting security forces inside a notorious camp, known as Al Hol, in the Syrian desert that holds tens of thousands of Islamic State members and their families, Syrian and U.S. officials said.

What was the reaction to the Trump order?

U.S.A.I.D. officials have been bracing for a drastic reduction to their ranks since contractors started being let go just days after the Trump administration’s stop-work order. But Democratic lawmakers say the moves to dismantle the agency or merge it with the State Department are illegal.

Two unions representing U.S.A.I.D. employees on Thursday filed a lawsuit against Mr. Trump, Mr. Rubio, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and the agencies they lead. The suit argued that the reduction in personnel and the cancellation of global aid contracts were unconstitutional and violated the separation of powers.

It sought an injunction to stop the firing and furloughing of employees and the dismantling of the agency. It argued that U.S.A.I.D. cannot be unwound without the previous approval of Congress.

“What we’re seeing is an unlawful seizure of this agency by the Trump administration in a plain violation of basic constitutional principles,” said Robin Thurston, the legal director for Democracy Forward, one of two advocacy organizations that filed the lawsuit on behalf of the American Foreign Service Association and American Federation of Government Employees. He added that the administration had “generated a global humanitarian crisis.”

On Friday afternoon, after a hearing, Judge Carl Nichols of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia said he would issue a temporary restraining order pausing the administrative leave of 2,200 U.S.A.I.D. employees and a plan to withdraw nearly all the agency’s overseas workers within 30 days.