Our problems begin with a statement purported to have been made by Marcus Garvey in the 1920s:

Look to Africa, when a black king shall be crowned for the day of deliverance is near

A few clarifications need to be made from the onset – Firstly, there is no proof that Garvey made such a statement and some people have attributed it to Reverend James Morris Webb who may have said something to that effect at a convention in 1924. Secondly, even if he said it, Garvey’s appraisal of Selassie was provably scathing and most uncharitable thus rebuffing any romanticization of the emperor’s legacy. Garvey called Selassie “a great coward” and “the leader of a country where black men are chained and flogged”. Ernest Cashmore’s Dictionary of Race and Ethnic Relations says, “…what Garvey said was less important than what he was reputed to have said”. And so the world romanticized with the mythical black savior instead of confronting the reality of the man who made many mistakes.

The West’s Favorite Dictator

On March 8 in 1964, the New York Times ran a story on the Emperor with a long, convoluted title that ironically betrayed the publication’s goal to confuse the reader into believing a despotic slave-owner could be the best thing that ever happened to Africa. “An Emperor Tries to Unite Africa; A generation older than other leaders. a moderate among radicals and Africa’s last feudal monarch, Haile Selassie has taken on the task of forging Pan‐African unity,” so went the title. The article admitted that Selassie was not the father of African unity because Kwame Nkrumah had preceded him.

However, Nkrumah’s urgent message of African unity was reduced to an impractical dream of an “egocentric hothead” while Selassie became the reasonable “moderate”. In what could have easily been mistaken for a glowing obituary, the article read, “The Emperor is imperturbable and he is a good negotiator. As a conciliator, he works on each disputant separately, winning his confidence, and explaining to each what he has to gain from a proposed compromise. He speaks carefully and never suggests radical change.” The key lay under the rubble of flattery: He never suggests radical change. That is why they preferred him to “hotheaded” Nkrumah.

Robert Hariman, in Political Style: The Artistry of Power, thus concluded that, “At once African and darling of the West, Selassie appropriated the traditions and mythic history of a monarchy to maintain a modern dictatorship, and while portrayed as a model of royal prerogative, and African independence, he served the interests of European imperialism.” Similarly, Gérard Prunier, a French author said of Selassie, “Foreign powers were well aware of the reactionary, unbearable and oppressive nature of the Ethiopian Solomonic dynasty but they all had favorite dictators – and the emperor was a magnificent one.” Ethiopia was especially close to the United States of America and the country only pivoted to Russia after the revolution that deposed Selassie.

An ordinary man

“I am not a Negro at all; I am Caucasian,” is probably the most unfortunate manifestation of a schizophrenic identity crisis in recorded history. To ice the irony, it was the black savior himself, Emperor Haile Selassie who made the clarification to pan-Africanist, Benito Sylvain. Since the Emperor thought of himself as something other than a Negro, it is quite unsurprising that he was slow to outlaw slavery. In fact, after much pressure from abolitionists in Britain, the Emperor had said slavery was a traditional economic institution in Ethiopia and if Ethiopians would read the articles written of it, a revolution would break out.

The Emperor, therefore, sat on the issue for so long that Italy used that inertia as an excuse to invade Ethiopia in 1935. Upon the invasion, Marcus Garvey justifiably accused Selassie of being a slavemaster. Attacking Haile Selassie’s contrived divinity, Garvey said, “After all, Haile Selassie is just an ordinary man like any other human being. What right has he to hold men as slaves?” But maybe the problem has always been that he has been treated like the god he is not. This is, after all, the same Haile Selassie who annexed Eritrea in 1962 in indefensible circumstances that went against the United Nations imposed federation.

A lot more could be said about the Emperor, the Negusa Nagast (King of Kings) and the Messianic figure whose mythos has overshadowed his true legacy. Hidden in the puffery and unsustainable pan-African legacy are some truths: He indeed managed to get African leaders together (albeit on conciliatory and more placatory terms to the world order than Nkrumah would have done). Once one accepts he was no god, it is easy to appreciate his complexity as an ordinary human being without the trappings of perfection that are expected of deities. Let Haile Selassie be an ordinary man like any other human being for his mistakes prove that is all he was.

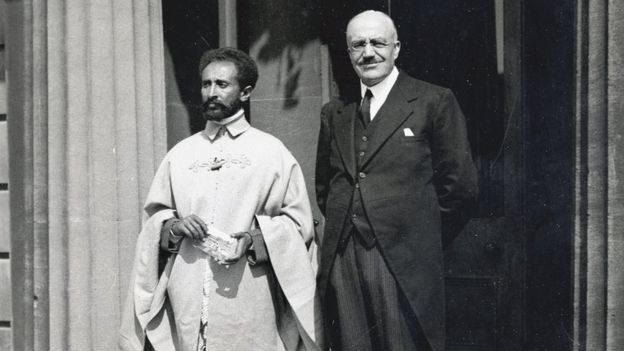

Image Credit: Dan Brown